Overview

In an excerpt from the introduction of Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), author Dawn Peterson looks at a group of white slaveholders who adopted Southeast Indian boys (Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw) into their plantation households in the decades following the US Revolution. While these adoptions might seem novel at first glance, they in fact reveal how the plantation household—and the racialized kinship structures that underpin it—increasingly came to shape human life for American Indians, African Americans, and Euro-Americans after the emergence of the United States.

From Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion by Dawn Peterson. Copyright © 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Introduction: Unusual Sympathies

In 1811 a prominent Choctaw woman named Molly McDonald placed her eleven-year-old son in the home of Silas Dinsmoor, an unpopular US government official who had just established a sprawling plantation in her homelands in what is now the state of Mississippi. Dinsmoor—who served as federal liaison between the Choctaw Nation and the US government—was openly disdainful of Choctaw people, politics, and sovereignty, viewing his slaveholding household as superior to the household arrangements of the Choctaw communities that surrounded him. Nonetheless, he eagerly incorporated McDonald's son into his family. Why would McDonald and Dinsmoor, whose interests appeared to be at odds, share a stake in McDonald's son?

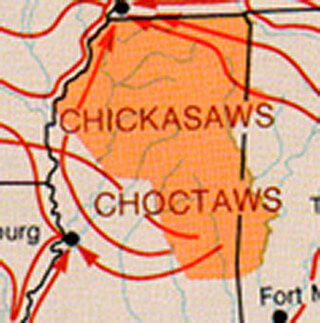

That question lies at the heart of this book. For as it turns out, the transfer of McDonald's son to Dinsmoor's care was not unique. In the decades following the US Revolution, a number of American Indian women and men and elite US whites supported the placement of Native children into "white" households throughout the existing United States. By the first decades of the nineteenth century, a small group of American Indians in the Southeast from the Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw Nations became particularly interested in sending their children—especially their sons—to live in slaveholding households in the US South. US slaveholders proved more than eager to oblige, enfolding Indian children into their domestic spaces and the white and black worlds that shaped them.

Map of the Indian tribes of North America about 1600 AD, Washington DC, 1836. Map by Albert Gallatin. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, loc.gov/resource/g3301e.ct000669/.

Most of the children who lived in US homes spent only short periods of time there, receiving educations in English language and literacy skills as well as in numeracy, literature, and Western philosophical and religious traditions. Those incorporated into US plantation households learned other lessons still as they watched white guardians try to assert mastery over the African and African American women, men, and children they enslaved. These US-educated youth then returned to their tribal nations—and their families—where many took up prominent leadership positions.

The Plumb-pudding in danger, a political cartoon depicting US and European imperialism, February 26, 1805. Cartoon etching by James Gillray. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, loc.gov/resource/cph.3g08791/.

Despite the brief nature of the majority of these domestic arrangements, those who housed and schooled Indian boys and girls understood their actions as a form of adoption. They saw themselves as absorbing Native children into their white families—however temporarily—and framed their actions as part of a broader initiative on the part of their new republic to assimilate Indian people into its expanding territorial borders. White adopters took their cue from some of the most influential governing officials of their day. As the United States aggressively pushed into Indian territories east of the Mississippi River between 1790 and 1830, a wide range of governing elites declared the importance of assimilating Indian people into the US body politic, which they described as a free white national family. Rather than emphasizing the various forms of violence required to dispossess Native people of their ancestral territories, government officials turned US imperialism into a family story, one supposedly capacious enough to include American Indian people—but not blacks—within "white" kinship systems, the foundational familial frameworks that shaped the rights of citizenship.1I am indebted to the work of black feminist thinkers and scholars in Native American and Indigenous studies and Queer studies in my analysis of family, race, and citizenship. See, for example, Brackette F. Williams, "The Impact of the Precepts of Nationalism on the Concept of Culture: Making Grasshoppers of Naked Apes," Cultural Critique 24 (1993): 143–91; Patricia Hill Collins, "It's All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation," Hypatia 13, no. 3 (1998): 62–82; Lisa Duggan, Sapphic Slashers: Sex, Violence, and American Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000); Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Mark Rifkin, When Did Indians Become Straight?: Kinship, the History of Sexuality, and Native Sovereignty (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). A number of established and would-be government officials themselves incorporated Indian children into their family spaces. Andrew Jackson—perhaps the most infamous figure in nineteenth-century US history for his assaults on Indian sovereignty and Indian lives—embraced the discourse of adoption as he and other US slaveholders worked to acquire Southeast Indian territories for the US plantation economy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. After invading Creek territories in what is now Alabama in 1813 and ordering the destruction of a Creek village—and the massacre of the women, children, and men who lived there—Jackson pronounced an "unusual sympathy" for a Creek infant orphaned by his troops. The Southern general sent the child home to be adopted into his plantation household in Nashville, Tennessee.2Andrew Jackson to Rachel Jackson, November 4 and December 19 and 29, 1813, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser, Sharon Macpherson, and Charles F. Bryan Jr., vol. 2, 1804–1813 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985), 444, 494–95, 516; Robert Vincent Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 192–94; Michael Paul Rogin, Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2006), 189.

Battle of Talladega, 1855. Engraving by unknown creator. Courtesy of the New York Public Library Art and Picture Collection Division, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f6d5-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

In current times, the term "adoption" relates to a specific liberal familial and reproductive arrangement whereby an individual or a two-parent couple legally asserts exclusive parentage rights over a child or children who are not immediate offspring.3The field of adoption studies has grown quite large in recent years. For both histories of adoption as a legal practice in the United States and the social and cultural parameters determining who qualifies as an adoptive parent and an adoptable child, see, for example, Jamil S. Zainaldin, "The Emergence of a Modern American Family Law: Child Custody, Adoption, and the Courts, 1796–1851," Northwestern University Law Review 73, no. 6 (1979): 1038–89; Rickie Solinger, Beggars and Choosers: How the Politics of Choice Shapes Adoption, Abortion, and Welfare in the United States (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002); Laura Briggs, Somebody's Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Brigitte Fielder, "'Those People Must Have Loved Her Very Dearly': Interracial Adoption and Radical Love in Antislavery Children's Literature," Early American Studies 14, no. 4 (Fall 2016): 749–80. Within this framework, adopted children are by law full members of their adoptive families, with no fewer rights than children born into these kinship units. The vast majority of the US whites incorporating American Indian children into their homes during the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries did not see their roles in these legalistic terms, nor is there any evidence that the Indian children living within these domestic spaces believed themselves to be similar in status to the household's white children. Further, not all white guardians used the term "adoption" per se when it came to defining their relationships with the Indian children in their care. At this time, adoption had not yet been formally codified in the United States. Up until the mid-nineteenth century, in fact, adoption was a rather unpopular practice among US whites due to common beliefs that only "blood" relations should inherit family property as well as to the continued availability of other forms of voluntary and involuntary child transfer, such as wardship and indenture. These prevailing guardianship practices at times left both birth parents and surrogate caretakers with some form of legal authority over the children in question, which could lead to conflicts over parental rights and responsibilities. Those who did formally adopt children during this era typically legitimated their parental status and their adopted children's inheritance rights through specific legislative acts.4Michael Grossberg, Governing the Hearth: Law and the Family in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 268–69. Massachusetts would pass "the first modern adoption law in history" in 1851, setting a precedent for, in the words of legal historian Jamil S. Zainaldin, "the judicially monitored transfer of rights with due regard for the welfare of the child and the parental qualifications of the adopters."5Zainaldin, "The Emergence of a Modern American Family Law," 1042–43, emphases in original. See also Grossberg, Governing the Hearth, 269–80.

This book's use of the term "adoption" more flexibly denotes an array of practices focused on the assimilation of Indian youths that were held together by declared desires on the part of US whites to situate Indian people as members of the US body politic. Within this framework, Indian people were supposed to enjoy liberty in the United States, but were also to remain socially and politically subservient to US whites. Unlike people of African descent, whose identities became synonymous with slavery—a status that denied black people the very rights or recognition of kinship—Indians were described as free people who could potentially be incorporated into the US national family, a process that in turn mandated that Indians adopt the social, economic, and familial values associated with white US society.6 On enslaved families' lack of legal rights, see Peter W. Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and the Law in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 31. On antebellum white society's reluctance to adopt African American children—or to even recognize their status as young people in need of actual protection and care—see Fielder, "'Those People Must Have Loved Her Very Dearly.'" Desires to adopt Indians into the United States reflected ambitions to position Indian people as at once on an equal footing to whites yet simultaneously pliable to white demands. Indians were to be assimilated as free children within the white national family, yet they were also supposed to remain permanent youth whose social, political, and intellectual maturity was constantly deferred.

Those who believed they could incorporate Indian people into the United States on their own terms quickly came to confront Native resistance strategies that they had not expected. A number of American Indian communities saw significant utility in placing their children among US whites for schooling. In the North, those whose lands stood in close proximity to US settlements were especially keen on acquiring for both young girls and boys English language and literacy skills as well as a facility in technical arts— particularly spinning, for women—in order to better position themselves economically and politically with respect to their acquisitive white neighbors. Native families' placement of young children within US homes was not a sign of their subservience to the United States but quite the opposite. The forms of knowledge their children could obtain in the midst of empire would better allow these youths and their extended families to oppose it.

American Indian nations throughout North America had their own indigenous definitions of captivity, slavery, and adoption, ones that evolved over time and, particularly in the Southeast, took on increasingly racialized characteristics in concert with European and US colonial invasions into their homelands.7For examinations of these changing histories, see, for example, Miles, Ties That Bind; Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). These shifting understandings of warfare, race, labor, and kinship directly shaped Native decisions to place their children in US homes. Among the Southeast Indians who sent their children away, most appear to have at least entertained ambitions to hold people of African descent as slaves, if they were not already engaging in the practice of racial slavery. Rather than viewing white guardians as the permanent adoptive parents of their children, most of these families sent their children to live in US households with the full expectation that their youth would return home and use the skills they had acquired in US homes in the service of self-determination. And their children did return. Although Andrew Jackson's adopted son—who came to be called Lyncoya—was an exception, many of the Southeast Indian men schooled within the United States used their educations in dramatically different ways than their adopters intended. After learning the ideas and practices forwarded by their US mentors—including those revolving around antiblack racism and plantation slavery—they drew upon their knowledge and experiences to oppose US Southerners seeking to dispossess tribal nations of their homelands.

While the number of Indian children living in US households was relatively small, the study of their lives and their migrations is illuminating.8 It is impossible to fully assess the numbers of Native children "adopted" by US whites during this period of study due to uneven record keeping on the part of US educational institutions and missionary organizations, the transient nature of many of these "adoptions," and the fact that many records have simply not survived into the present. This book accounts for small numbers (fewer than thirty). However, all told, there were an additional forty-two Indian children living in Cornwall, Connecticut, over the course of the 1810s and 1820s, as well as fluctuating numbers of Native youth at a residential school called Choctaw Academy in Blue Springs, Kentucky, opened in 1825. In addition, in 1824 the US House Committee on Indian Affairs estimated that over eight hundred Indian children had attended mission schools within Indian territories. See Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 152. For scholarly accounts regarding the numbers of children at Cornwall mission school and Choctaw Academy, see John Demos, The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic (New York: Knopf, 2014), 231; Carolyn Thomas Foreman, "The Choctaw Academy," Chronicles of Oklahoma 6, no. 4 (1928): 453–80. The political and familial commitments of white adopters, American Indian parents, and adopted Indian children offer a unique vantage point into eighteenth- and nineteenth-century nation building on the part of the early US republic and those American Indian nations forced to contend with it. The expansionist visions of US settlers and the complex forms of resistance engaged in by American Indian women and men in the decades before the forced relocation of tens of thousands of Indian people living east of the Mississippi River to the trans-Mississippi West reveal how a subset of whites and Southeast Indians used adoption, kinship, and slavery to impose and resist US imperial rule. For white adopters, incorporating Indian children into their homes supported US settler expansion. For the select group of American Indian women and men who placed their girls and boys in US homes, acquiring the forms of knowledge valued within the settler societies in their midst was a crucial step in assuring political, economic, and territorial sovereignty.

By the early 1800s a small but powerful class of Southeast Indian elites saw white slaveholders' interest in incorporating Native children into their plantation homes as particularly useful. With US planters invading the Southeast at unprecedented rates, these Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee, and Chickasaw women and men sent sons to acquire the racialized educations that increasingly supported political and economic authority in the slaveholding South. US expansionists would come head-to-head with these Native strategists in the 1820s. Through their selective engagement with some of the colonial logics and practices that drove US settler expansion in general, and the plantation economy in particular, adopted Southeast Indian sons effectively thwarted state and federal claims to their lands, so much so that Southern slaveholders advocated for the forced removal of Southeast Indian nations west of the Mississippi River in 1830.9As scholar Alexandra Harmon argues, "the banishment of Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks was a response to competition between peoples with comparable agendas and comparable enterprising classes." Alexandra Harmon, Rich Indians: Native People and the Problem of Wealth in American History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 93. Indians' access to US domestic regimes proved more threatening than most US imperialists had anticipated. Instead of being solely an imperial practice of assimilation, adoption proved a Native-driven strategy of infiltration, allowing elite Indian men privileged access to and knowledge about powerful and influential spaces within an expanding US empire.

The transfer of American Indian children into foreign homes and institutions during the post-Revolutionary period reflects both a continuity in European and Euro-American relationships with Indian people and a distinct moment in North American history. On the one hand, the practice existed prior to the formation of the United States and would endure long after the forcible relocation of American Indian nations during the 1830s. Well before Molly McDonald sent her son to live in a Mississippi plantation household or Andrew Jackson raided the Creek Nation, American Indian people found themselves living in European and Euro-American homes. Christopher Columbus enslaved Native people from the Caribbean after his first voyages to the Americas, inaugurating a practice that persisted among the French, Spanish, and British empires and within some US settlements well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.10Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, A.D. 500–1600 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 105; Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), esp. 13–45. A number of recent monographs and edited volumes have documented British, French, Spanish, and US participation in the enslavement of American Indians. See, for example, ibid.; Alan Gallay, ed., Indian Slavery in Colonial America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010); Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002); James F. Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). In 1561 Spanish adventurers took a young man—who some believe was probably a member of the Chiskiak tribe—from the Chesapeake region. Dubbed Don Luis de Velasco, he was trained in the Spanish language and Christian religion in Mexico and then sailed back to the Chesapeake on two Spanish colonization expeditions to serve as a guide and interpreter. (Much to Spanish dismay, Don Luis apparently sabotaged both expeditions, eventually returning to his people in 1570).11Camilla Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, American Portraits (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), 7–9. In 1584 English explorers attempting to establish their empire's first colonies in North America carried two Algonquian-speaking Indians from the Chesapeake region back with them to England. One was Manteo, the son of the leader of the Croatoan polity, and the other was Wanchese, who hailed from the Secotans. These young men's voyage appears to have been more voluntary than those migrations previously orchestrated by the Spanish, as the English left two of their own men in exchange for their Native travelers. Manteo and Wanchese, however, would develop very different impressions of their European hosts during their stay in London, which would influence their relationships with British colonists upon their later return to their homelands in what would become known as Virginia. Manteo declared himself fairly treated and developed a lasting alliance with British colonists, one that he undoubtedly hoped would better conditions for his own people. Wanchese, on the other hand, did not trust the British empire and, once back in his own community, worked to unseat the unwelcome settlers who proved to be disloyal and treacherous in their treatments of Indian people.12James Horn, A Kingdom Strange: The Brief and Tragic History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 55, 60–61, 81–82, 92, 155, 157–60.

The Roanoke settlement that threatened Wanchese's community disappeared within a matter of years. However, the Jamestown settlement that would arise in its wake also circulated Indian people through the British metropole, most famously in the case of Amonute, who would become known to the British by her nickname, Pocahontas.13Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, 13–14. Initially held hostage by Jamestown settlers, Amonute eventually married into the British community and traveled to London with her husband and their infant son. Like Manteo, she made the journey to improve conditions for her Native polity— in this case the powerful confederacy built up by her father, Powhatan—as the English took more and more territory by force. Her death in London from illness cut short her attempts at diplomacy and the promotion of coexistence between the two polities.14 Ibid., esp. 85–158. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as British colonists claimed territories in what would become known as New England, as well as in the mid-Atlantic and in the South, other Indian people would choose to enter into English households—and, later, into English-run schools—in order to learn the English language and understand the spiritual beliefs that they believed might help them to better navigate British settlement and the devastation it wrought.15 Jean M. O'Brien, Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 54; Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 30–39. For a useful overview of Indian schooling by European-descended settlers, see Margaret Connell Szasz, Indian Education in the American Colonies, 1607–1783 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988). Others still found themselves held in colonial households by force. Indeed, European settlers' desires for Indian slaves and indentured servants put countless Indian people—particularly women and children—in Euro-American homes, dramatically reshaping Native politics, communities, and even nations in the process.16Gallay, Indian Slave Trade; Robbie Ethridge and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, eds., Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Gallay, Indian Slavery in Colonial America; Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau, "The Right to a Name: The Narragansett People and Rhode Island Officials in the Revolutionary Era," in After King Philip's War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1997), 115, 121–24, 127.

Jumping forward to the close of the nineteenth and first decades of the twentieth century, the US federal government endorsed the forced relocation of American Indian children into boarding schools, hoping to erase a new generation's indigenous cultural and kinship ties and, by extension, their claims to their homelands.17David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997). For how Native parents and children navigated the trauma of this history, see Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000). Here, too, Indian children went into the households of US whites as families "adopted out" from boarding schools, a practice that often translated into the indenture of Indian girls and boys as laborers on US farms and in white homes.18See Sarah Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 71. For a compelling memoir of one man's experiences of being put in a residential school and then placed in an abusive white family in the 1940s, see Peter Razor, While the Locust Slept: A Memoir (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002). Leslie Marmon Silko provides a powerful novel that engages with the history of this practice. See Leslie Marmon Silko, Garden in the Dunes: A Novel (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000). Throughout the twentieth and into the present century, American Indian families have faced ongoing struggles to protect their children from US adoption and fostering practices. State and federal agencies and private adoption services continue to undermine both the familial and national rights of indigenous people by transferring children away from their Native kin and tribal communities to wealthier—and most often white—families, despite existing laws aimed to protect Indian families and nations from precisely these kinds of predatory processes. In the words of Muscogee legal scholar Sarah Deer, such ongoing forms of child removal have "sent a variety of messages to tribal communities, particularly to mothers. The dominant society disapproved of the way Native people parented."19Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape, 85. See also Briggs, Somebody's Children, 59–93; Laura Briggs, "Why Feminists Should Care about the Baby Veronica Case," Indian Country Today Media Network, August 16, 2013, http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/08/16/why-feminists-should-care-about-baby-veronica-case-150894; Laura Sullivan and Amy Walters, "Native Foster Care: Lost Children, Shattered Families," NPR News, October 25, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/10/25/141672992/native-foster-care-lost-children-shattered-families.

Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, ca. 1892. Photograph by unknown creator. Courtesy of New York Public Library Art and Picture Collection Division, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-1b90-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Like their predecessors and their later counterparts, white adopters in the Revolutionary and early national period believed themselves to be superior to American Indian people and drew upon this sense of entitlement as they encouraged the separation of Native children from their families and into white-controlled spaces. They believed the right to have children and to control the upbringing of young people was the privilege of white settlers and not of those whose lands they invaded. Settler colonialism revolves around the foreign settlement of indigenous land and the subsequent declaration on the part of colonists of their own nativity to indigenous space, a move that correspondingly defines indigenous people as foreigners in, or alien to, their own homelands.20See, for example, Jean M. O'Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native," Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409; J. Kēhaulani Kauanui and Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism Then and Now: A Conversation," in special issue, ed. Michele Spanò, Politica & Società (June 2012): 235–58. Within this formulation, indigenous people are not only positioned as unworthy of reproducing their own communities as they see fit but are actively prevented from doing so. The goal of settlers is to circumscribe or eliminate both the power and the populations of indigenous people so as to make lands and resources available to colonizers.21Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native." Within the context of British and US settlement of North America, when settlers encouraged—or even demanded—the migration of American Indian children into their homes, they were hoping to erase or severely limit autonomous Native futures outside of the purview of the British colonies or the United States.

During the early national period, US officials were formulating expansionist policies oriented around the geopolitics of racial slavery and in direct response to specific American Indian resistance strategies developed to thwart US imperial ambitions. In this particular historical moment, the politics of adoption took on singular importance, becoming a means to define citizenship within a slaveholding republic and to undermine indigenous resistance struggles based upon pan-Indian unity movements and transatlantic commercial, trade, and military alliances with European empires. Adoption signaled who could be incorporated into a free white national family—and who could not—and structured imperial policies aimed at assimilating American Indian people and the nations to which they belonged into a US "domestic" economy. As Indians' powerful international connections began to crumble in the face of US policies and shifting European geopolitical interests by the first decades of the nineteenth century, however, adoption also became a way for Native people to defend themselves against exploitative US international agendas and economic systems, especially as the possibilities for military defense evaporated.

Racial slavery—and the ideas about "blackness," "whiteness," and "Indianness" it helped to engender—sat at the heart of US contests over human beings and territory. It determined who would—or could—occupy specific household and territorial spaces, shaped economic relationships and political governance across US settlements, and calibrated the kinship systems informing how individual women, children, and men were able to labor, live, and love. With plantation slavery directly driving US colonization of the Southeast—the region that would become known as the "Deep South"—and a small but influential group of Southeast Indian women and men themselves beginning to hold black people as property, chattel slavery came to shape decisions by a number of mothers, fathers, uncles, and aunts to send children to live in the United States. The women and men who placed their children within US slaveholding households acted in ways to better position themselves—and often their tribal nations more broadly—within rapidly changing imperial worlds. Yet they also subjugated people of African descent, a move that distinguished them from the vast majority of the individuals living within their Native nations, not to mention in American Indian nations across the continent.22For histories of slavery in Indian country, see, for example, James Taylor Carson, Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 80; Miles, Ties That Bind, 75; Celia E. Naylor, African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 17; Theda Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540–1866 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979); Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country. It lent them their own unusual sympathies with the very slaveholders who sought to dispossess them of their homelands.

By following a series of families and the ways in which the lives of the individuals who composed them intersected across nations and empires, the stories told in the following chapters seek to provide an intimate glimpse into the history of nation building—and of attempts to destroy indigenous nations—in post-Revolutionary North America.23Drawing on the work of sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, historian Tiya Miles argues that the "family can . . . be read as a barometer for . . . society, tracing and reflecting the atmospherics of social life and social change." Ties That Bind, 3. For compelling studies on the intersections of family relationships and Euro-American imperialism, see ibid.; Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001); Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800–1860 (New York: Ecco, 2012); Emma Rothschild, The Inner Life of Empires: An Eighteenth-Century History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012). Adoption, expansion, and slavery would serve as important and intertwined practices in these familial, national, and imperial stories, shaping the daily lives of people of American Indian, African, and European descent and influencing US and Southeast Indian political governance. Ideas about kinship and race became central in competing claims to land, labor, and citizenship in the post-Revolutionary era. They directly informed imperial policy decisions and articulations of self-determination, structuring a diverse range of struggles for individual and collective sovereignty and freedom in the process.

Acknowledgments

Southern Spaces thanks Harvard University Press for their permission to reprint this excerpt from the introduction of Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion.

About the Author

Dawn Peterson is an assistant professor of early North American and US history at Emory University. In her research, she considers the roles of race, gender, and kinship in the history of US capitalism, settler colonialism, and slavery, particularly in the post-Revolutionary period. Her book Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017) looks at a group of white slaveholders who adopted Southeast Indian boys (Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw) into their plantation households in the decades following the US Revolution. While these adoptions might seem novel at first glance, they in fact reveal how the plantation household—and the racialized kinship structures that underpin it—increasingly came to shape human life for American Indians, African Americans, and Euro-Americans after the emergence of the United States. Peterson has received fellowships to support this work from the American Antiquarian Society, Harvard University, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the Huntington Library, the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, and the Newberry Library.

Recommended Resources

Text

Berger, Thomas R. A Long and Terrible Shadow: White Values, Native Rights in the Americas since 1492. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Grossberg, Michael. Governing the Hearth: Law and the Family in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

Miles, Tiya. Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and in Freedom. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Razor, Peter. While the Locust Slept: A Memoir. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002.

Wolfe, Patrick. "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native." Journal of Genocide Research 8 (2006): 387–409.

Web

"Adoption: An Overview." Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Accessed August 17, 2017. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/adoption.

Herman, Ellen. "The Adoption History Project." University of Oregon. Acessed August 17, 2017. http://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/index.html.

"Native Voices." Digital History. Accessed August 17, 2017. http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/voices/voices_content.cfm?vid=4.

Onion, Rebecca. "Andrew Jackson's Adopted Indian Son." Slate. April 29, 2016. Accessed August 17, 2017. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2016/04/andrew_jackson_s_adopted_son_lyncoya_why_did_jackson_bring_home_a_creek.html.

"Policy Issues." National Congress of American Indians. Accessed August 17, 2017. http://www.ncai.org/policy-issues.

Prillaman, Barbara. "Indian Boarding Schools: A Case Study of Assimilation, Resistance, and Resilience." Yale National Initiative. Accessed August 17, 2017. http://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_16.01.09_u#top.

"Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730–1842." Digital Library of Georgia. Accessed August 17, 2017. http://neptune3.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/ftaccess.cgi?_id=7f000001&dbs=ZLNA.

Similar Publications

| 1. | I am indebted to the work of black feminist thinkers and scholars in Native American and Indigenous studies and Queer studies in my analysis of family, race, and citizenship. See, for example, Brackette F. Williams, "The Impact of the Precepts of Nationalism on the Concept of Culture: Making Grasshoppers of Naked Apes," Cultural Critique 24 (1993): 143–91; Patricia Hill Collins, "It's All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation," Hypatia 13, no. 3 (1998): 62–82; Lisa Duggan, Sapphic Slashers: Sex, Violence, and American Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000); Tiya Miles, Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006); Mark Rifkin, When Did Indians Become Straight?: Kinship, the History of Sexuality, and Native Sovereignty (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Andrew Jackson to Rachel Jackson, November 4 and December 19 and 29, 1813, in The Papers of Andrew Jackson, ed. Harold D. Moser, Sharon Macpherson, and Charles F. Bryan Jr., vol. 2, 1804–1813 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1985), 444, 494–95, 516; Robert Vincent Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Empire, 1767–1821 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 192–94; Michael Paul Rogin, Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2006), 189. |

| 3. | The field of adoption studies has grown quite large in recent years. For both histories of adoption as a legal practice in the United States and the social and cultural parameters determining who qualifies as an adoptive parent and an adoptable child, see, for example, Jamil S. Zainaldin, "The Emergence of a Modern American Family Law: Child Custody, Adoption, and the Courts, 1796–1851," Northwestern University Law Review 73, no. 6 (1979): 1038–89; Rickie Solinger, Beggars and Choosers: How the Politics of Choice Shapes Adoption, Abortion, and Welfare in the United States (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002); Laura Briggs, Somebody's Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Brigitte Fielder, "'Those People Must Have Loved Her Very Dearly': Interracial Adoption and Radical Love in Antislavery Children's Literature," Early American Studies 14, no. 4 (Fall 2016): 749–80. |

| 4. | Michael Grossberg, Governing the Hearth: Law and the Family in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 268–69. |

| 5. | Zainaldin, "The Emergence of a Modern American Family Law," 1042–43, emphases in original. See also Grossberg, Governing the Hearth, 269–80. |

| 6. | On enslaved families' lack of legal rights, see Peter W. Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, and the Law in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 31. On antebellum white society's reluctance to adopt African American children—or to even recognize their status as young people in need of actual protection and care—see Fielder, "'Those People Must Have Loved Her Very Dearly.'" |

| 7. | For examinations of these changing histories, see, for example, Miles, Ties That Bind; Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010). |

| 8. | It is impossible to fully assess the numbers of Native children "adopted" by US whites during this period of study due to uneven record keeping on the part of US educational institutions and missionary organizations, the transient nature of many of these "adoptions," and the fact that many records have simply not survived into the present. This book accounts for small numbers (fewer than thirty). However, all told, there were an additional forty-two Indian children living in Cornwall, Connecticut, over the course of the 1810s and 1820s, as well as fluctuating numbers of Native youth at a residential school called Choctaw Academy in Blue Springs, Kentucky, opened in 1825. In addition, in 1824 the US House Committee on Indian Affairs estimated that over eight hundred Indian children had attended mission schools within Indian territories. See Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984), 152. For scholarly accounts regarding the numbers of children at Cornwall mission school and Choctaw Academy, see John Demos, The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic (New York: Knopf, 2014), 231; Carolyn Thomas Foreman, "The Choctaw Academy," Chronicles of Oklahoma 6, no. 4 (1928): 453–80. |

| 9. | As scholar Alexandra Harmon argues, "the banishment of Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks was a response to competition between peoples with comparable agendas and comparable enterprising classes." Alexandra Harmon, Rich Indians: Native People and the Problem of Wealth in American History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 93. |

| 10. | Samuel Eliot Morison, The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, A.D. 500–1600 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 105; Andrés Reséndez, The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016), esp. 13–45. A number of recent monographs and edited volumes have documented British, French, Spanish, and US participation in the enslavement of American Indians. See, for example, ibid.; Alan Gallay, ed., Indian Slavery in Colonial America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010); Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002); James F. Brooks, Captives and Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); Brett Rushforth, Bonds of Alliance: Indigenous and Atlantic Slaveries in New France (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). |

| 11. | Camilla Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, American Portraits (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005), 7–9. |

| 12. | James Horn, A Kingdom Strange: The Brief and Tragic History of the Lost Colony of Roanoke (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 55, 60–61, 81–82, 92, 155, 157–60. |

| 13. | Townsend, Pocahontas and the Powhatan Dilemma, 13–14. |

| 14. | Ibid., esp. 85–158. |

| 15. | Jean M. O'Brien, Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 54; Jill Lepore, The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 30–39. For a useful overview of Indian schooling by European-descended settlers, see Margaret Connell Szasz, Indian Education in the American Colonies, 1607–1783 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988). |

| 16. | Gallay, Indian Slave Trade; Robbie Ethridge and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, eds., Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Gallay, Indian Slavery in Colonial America; Ruth Wallis Herndon and Ella Wilcox Sekatau, "The Right to a Name: The Narragansett People and Rhode Island Officials in the Revolutionary Era," in After King Philip's War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England (Hanover: University Press of New England, 1997), 115, 121–24, 127. |

| 17. | David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997). For how Native parents and children navigated the trauma of this history, see Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000). |

| 18. | See Sarah Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape: Confronting Sexual Violence in Native America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 71. For a compelling memoir of one man's experiences of being put in a residential school and then placed in an abusive white family in the 1940s, see Peter Razor, While the Locust Slept: A Memoir (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002). Leslie Marmon Silko provides a powerful novel that engages with the history of this practice. See Leslie Marmon Silko, Garden in the Dunes: A Novel (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000). |

| 19. | Deer, The Beginning and End of Rape, 85. See also Briggs, Somebody's Children, 59–93; Laura Briggs, "Why Feminists Should Care about the Baby Veronica Case," Indian Country Today Media Network, August 16, 2013, http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/08/16/why-feminists-should-care-about-baby-veronica-case-150894; Laura Sullivan and Amy Walters, "Native Foster Care: Lost Children, Shattered Families," NPR News, October 25, 2011, http://www.npr.org/2011/10/25/141672992/native-foster-care-lost-children-shattered-families. |

| 20. | See, for example, Jean M. O'Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native," Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 387–409; J. Kēhaulani Kauanui and Patrick Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism Then and Now: A Conversation," in special issue, ed. Michele Spanò, Politica & Società (June 2012): 235–58. |

| 21. | Wolfe, "Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native." |

| 22. | For histories of slavery in Indian country, see, for example, James Taylor Carson, Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 80; Miles, Ties That Bind, 75; Celia E. Naylor, African Cherokees in Indian Territory: From Chattel to Citizens (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 17; Theda Perdue, Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540–1866 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979); Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country. |

| 23. | Drawing on the work of sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, historian Tiya Miles argues that the "family can . . . be read as a barometer for . . . society, tracing and reflecting the atmospherics of social life and social change." Ties That Bind, 3. For compelling studies on the intersections of family relationships and Euro-American imperialism, see ibid.; Susan Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001); Juliana Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Tiya Miles, The House on Diamond Hill: A Cherokee Plantation Story (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800–1860 (New York: Ecco, 2012); Emma Rothschild, The Inner Life of Empires: An Eighteenth-Century History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012). |