Overview

James Taylor Carson reviews Gregory D. Smithers's The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

Whenever the concepts of diaspora and indigeneity come together, scholars tend to ascribe oppositional power to them. Diaspora implies transnational if not global movement, displacement, and attenuation while indigeneity connotes originality, belonging, and rootedness. In drawing together diaspora and indigeneity to compass the complexities and ambiguities of indigenous peoples' lives, scholars of indigenous diasporas have closed the gap between the two concepts. They suggest that in spite of diasporic indigenous persons' relationships to multiple places—a lost homeland, a current abode, a far-away site of work—and to multiple identities—clan, tribal, historical, racial, and political—diasporic indigenous peoples can and do remain rooted in common memories, traditions, and pasts.1William Safran, "Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return," Diaspora 1 (July 1991): 83–99; Michele Reis, "Theorizing Diaspora: Perspectives on 'Classical' and 'Contemporary' Diaspora," International Migration 42 (June 2004): 41–60; Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997); Rogers Brubaker, "The 'Diaspora' Diaspora," Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (January 2005): 1–19; Paul Burke, "Indigenous Diaspora and the Prospect for Cosmopolitan 'Orbiting': The Warlpiri Case," Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 14 (August 2013): 304–7; James Clifford, "Indigenous Articulations," Contemporary Pacific 13 (Fall 2001): 470–72, 478–79; Robin Delugan, "Indigeneity across Borders: Hemispheric Migrations and Cosmopolitan Encounters," American Ethnologist 37 (February 2010): 41–2.

Gregory D. Smithers's The Cherokee Diaspora offers one of the first diasporic studies of Native North America. The idea of diaspora allows Smithers to remove Cherokee history from the usual linear settler/colonial paradigm that frames the subject and to instead address long and recurring cycles of Cherokee dislocation, movement, and coalescence. The problems that beset any diasporic people—a sense of belonging, of identity, and of home—have confronted Cherokees for centuries. How they responded to such challenges has varied over time as sense of self and place shifted from the sacred fires that centered each town in the eighteenth century to engagement with the federal government's so-called "civilization" policy in the early nineteenth century, to the valorization of blood quantum later in the nineteenth century, to federal law and competing indigenous notions of what it means to be Cherokee today. While such different formations enabled Cherokees to maintain a sense of peoplehood, there was often little agreement over who counted across time and space as a Cherokee. Contests over Cherokee identity became an insistent theme, but, Smithers concludes, one basic determinant above all others has defined being Cherokee since the 1830s: their shared history of expulsion from an ancestral homeland and their arduous and deadly forced march to the West along what is known as the Trail of Tears.

Scholars have wrestled with how to interpret and depict the cyclical unity of time, space, and place that gives indigenous peoples powerful identities and senses of place.2William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983); Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996); James Taylor Carson, "Ethnogeography and the Native American Past," Ethnohistory 49 (Fall 2002): 765–784; Robbie Ethridge, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). Smithers makes a promising start when he grounds his study in two Cherokee sensibilities, tohi and osi, which embody notions of flow, equanimity, and power. An individual's actions always implicate him or her in the flow of the world, posing a constant challenge to remain balanced and to flow well (53–4). By setting in motion a space where people flow, where rivers and mountains are alive, where the East is associated with the beginning of life and the West with its inevitable end, Smithers embeds Cherokees within a cosmological space that holds great promise as an interpretive entry into their past.

Such an auspicious spatial framing wanes over the course of The Cherokee Diaspora. As Smithers' explication of diaspora and modern identity becomes unmoored from the senses of space and place that tied them with great depth and specificity to their ancestral homeland, what remains is a fairly conventional narrative of post-removal Cherokee history. Cherokees, however, had emerged from the earth, their mother. What we gloss as trees, rocks, mountains, springs, streams, animals, and plants knit the Cherokees' knowledge of the world and its origins into a tight narrative that informed everything: how a child should behave, how to make a medicine, how to achieve peace. They were not people who inhabited a natural world; instead, the Cherokees were so implicated within the workings of the world that their lives played out in a complex mixture of time, space, and place that can be neither imagined nor perceived when disaggregated. The text also neglects a register of the profound, unexplored impact of losing their homeland. Loss of place often triggers drastic transformations in a sense of past, self, and future. Reconstituting themselves in Indian Territory was not just a struggle to resettle, build new homes, plant new gardens, and learn about new weather patterns. It demanded a reimagination of who the Cherokee were, how they connected to the world, and how they connected to their former ancestral home—all processes that lie at the core of the diasporic experience and demand closer attention.3Andrea L. Smith and Anna Eisenstein, Rebuilding Shattered Worlds: Creating Community by Voicing the Past (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 3–4, 11–13.

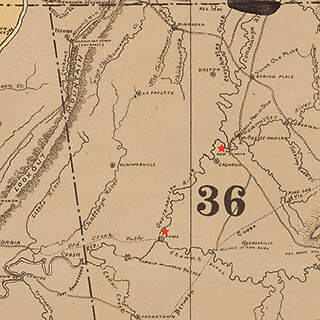

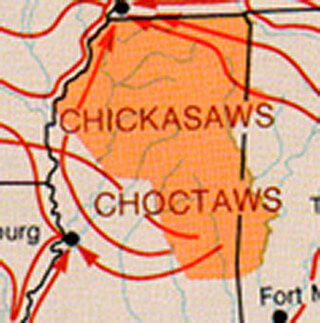

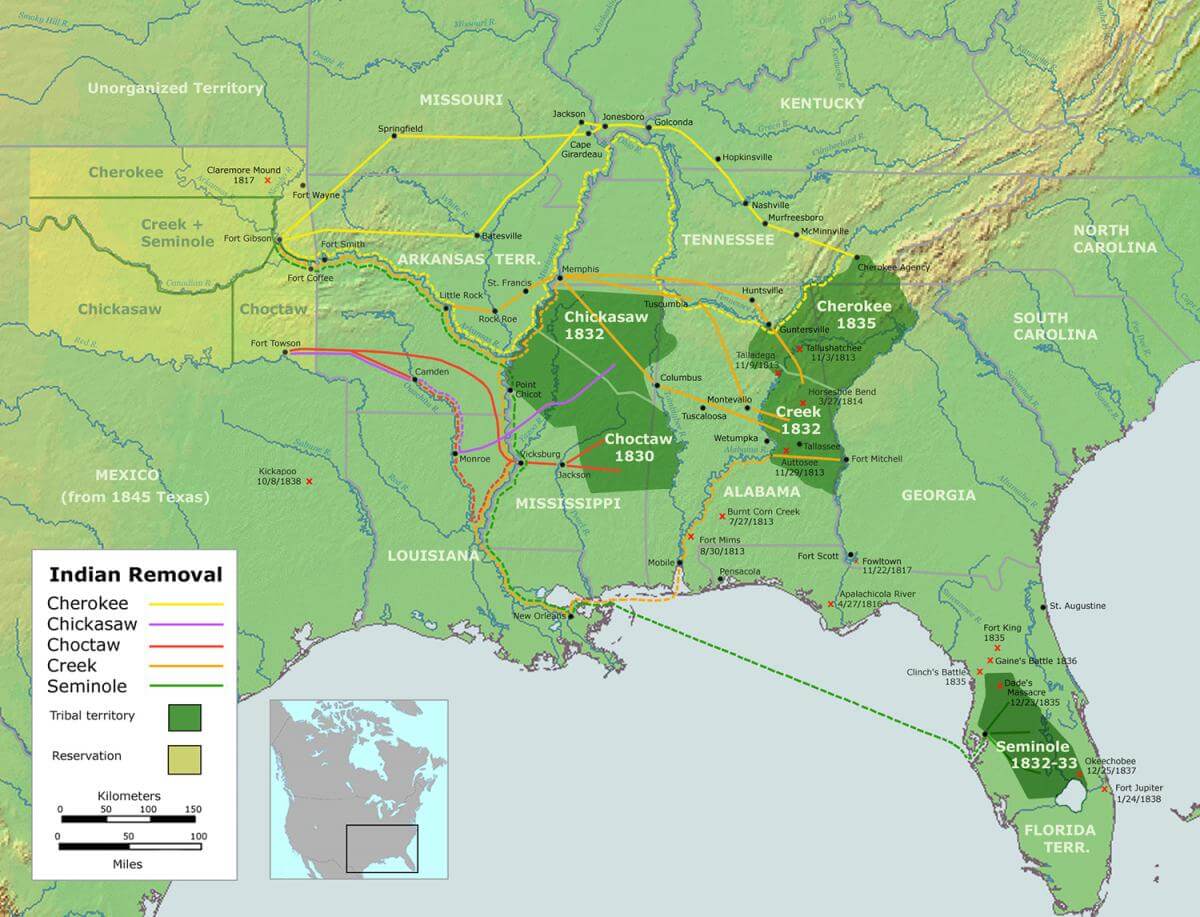

In a longer history, Cherokees arrived in the southern Appalachians about four-thousand years ago, having left their Iroquoian homeland, which itself was once a place of arrival for ancestors thousands of years before. The Cherokee diaspora that concerns Smithers began at the end of the American Revolution when a handful of prescient leaders in mountain towns of what is today Tennessee, Georgia, and North Carolina ascertained that the long knife republic was not going to abide by borders negotiated by the crown they had just overthrown. In anticipation of this invasion, Cherokees began to head west in search of places to ensure that they could remain in flow and balance. Over the following decades many more followed while others headed for the Mexican province of Texas in search of respite from Anglo-American encroachments. By 1830, Texas Cherokees numbered several hundred while around five thousand western Cherokees settled in present-day western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma. Many of the 16,500 who still inhabited their ancestral homeland in the states of Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina regarded their far-flung kin as either outsiders or as rivals who had abandoned them in their fight against the federal and state governments and who had turned their backs on the adoption of Anglo-American cultural norms. But when in 1838 and 1839 the US army expelled the remaining eastern Cherokees from Tennessee, with the exception of a few hundred who remained in western North Carolina, the relocation of the nation to what became known as Indian Territory was complete.

The land once home to a few thousand western Cherokees (what is today southeastern Oklahoma) transformed in the early 1840s into the site of a new nation that had to remake itself out of a population segmented by different histories of movement, identity, and resistance. In the wake of assassinations and bitter civil strife, the former leader of the eastern Cherokees, John Ross, forged a coalition in defense of their new homeland, a renewed sovereignty, and a proactive adaptation to life in Anglo-America. Over time the people who remained in North Carolina found themselves estranged from their western kin and increasingly excluded from the new nation's exclusive claims to Cherokee identity.

Two subsequent events, abolition and allotment, undermined the Cherokee identity fashioned in Indian Territory. Emancipation at the end of the Civil War created a new set of Cherokees out of the nation's enslaved population whose skin color made them anathema to most other Cherokees. The freed peoples' claims to certain legal rights and benefits hastened the nation's embrace of US racial norms and laws in order to exclude freed people from the census rolls that determined membership in the nation. Then, in the early 1900s, the federal government allotted most of the Cherokees' western land for sale to speculators and homesteaders. Allotment transformed the nation from a place that could be mapped on the ground to a space of the mind and heart that could only be felt and enacted through cultural rites, church services, and social gatherings. How Cherokees remained conscious of themselves as a people and how they reformulated a sense of self after allotment demands a deeper investigation than Smithers offers. It is unclear whether and how a sense of spatiality informed debates over who belonged and who did not. In eliminating formerly enslaved men, women, and children from the nation's rolls, Cherokees undertook a purging of collective genealogy and a restructuring of the spaces they inhabited. A different kind of removal required the political and racial separation of neighbors and kin.

Two world wars and the Great Depression further disrupted Cherokee life. Poverty, urban opportunities, and service overseas pushed and pulled Cherokees across the country as they sought belonging and work in US cities. By the 1970s, most still called Oklahoma home but thousands had sought better opportunities in California and other states. Some made it as far as Hawaii and a few even lodged applications with the Australian government. Meanwhile, the Cherokees in North Carolina had rebuilt their land base as the Qualla reserve and gained separate federal recognition to set themselves up as a second Cherokee nation.

In spite of confusing and complicated histories of dislocation, violence, and rivalry, Smithers argues that there is still a Cherokee people whose identity transcends a myriad of political, racial, and geographical divisions. Cherokees are, Smithers argues, defined by their shared diasporic experiences of the Trail of Tears. His inability to anchor consistently his interpretation in indigenous concepts of flow and propriety fails to clarify how understanding their expulsion can be usefully explored as a diaspora. At the heart of the story of the Cherokee diaspora sit the brute facts that they lost most of their ancestral homeland, were driven by force of arms from their homes, reconstituted themselves in a new homeland which they subsequently lost, and then underwent bitter struggles over who counted as a member of the nation and who did not. When held apart from specific ethnogeographic considerations, such a narrative comports well with other such studies. If, however, Smithers had probed more deeply the interdependence of peoplehood, place, and memory, and pushed his analysis back to the much earlier migration that brought the Cherokees to their southern homeland, he might have better represented the pain of expulsion from not just an ancestral homeland but from a living being that had borne and nurtured the Cherokees for millennia.

Consider the Cherokee dead, the ghosts that haunt TVA reservoirs, inhabitants of ancient cemeteries that lie beneath economic development projects, and occupants of forlorn mounds—the beings who tie the living to the past and to the land. They have stories to tell. According to notions of tohi and osi the dead are never really dead but cohabit with the living and the unborn. When real estate development and other forms of excavation disturb or destroy the Cherokee dead, Cherokee life is imperiled. The life that Cherokee ghosts enact draws time, space, and self into one conceptual and existential field, making stories about survival, endurance, hope, and belonging possible. They ensure that life continues to flow well and that Cherokees remain Cherokees and, above all else, grounded.4James Taylor Carson, "Cherokee Ghostings and the Haunted South," The Native South: New Histories and Enduring Legacies, eds. Tim Alan Garrison and Greg O'Brien (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 238–62.

It is not, in the end, altogether clear how the concept of diaspora reframes the standard story of Cherokee dispossession. Lacking a deeper exploration of place and space, Smithers' interpretive angle never closes on the emotional depth and psychic pain of removal and allotment, nor does it open a view into the transformative creativity needed to remake a homeland, both real and remembered, over and over. Nevertheless, Smithers has tried something new, seeking to set the history of Native North America on a different footing that engages with broader inquiry into transnational themes of identity, memory, and history. He demonstrates that the trauma of ethnic cleansing remains today in Cherokee minds and memories and at the core of their collective identity. That such trauma reaches out across almost two centuries indicates the need to find ways to open the past so that well-worn narratives can recover some of their original power to provoke and to disturb.

About the Author

James Taylor Carson is head of the school of Humanities, Languages and Social Science at Griffith University, Brisbaine, Australia. His research and writing has focused largely on issues related to contact between European invaders and first peoples in North America. His books include Making an Atlantic World: Circles, Paths, and Stories from the Colonial South (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2007).

Recommended Resources

Text

Chin, Jeremiah. "Red Law, White Supremacy: Cherokee Freedman, Tribal Sovereignty, and the Colonial Feedback Loop." J. Marshall Law Review 47, no. 4/5 (2014): 1227–1256.

http://repository.jmls.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2080&context=lawreview.

Denson, Andrew. Demanding the Cherokee Nation: Indian Autonomy and American Culture, 1830–1900. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

———. Monuments to Absence: Cherokee Removal and the Contest over Southern Memory. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Inniss, Lolita Buckner. "Cherokee Freedmen and the Color of Belonging." Law Faculty Articles and Essays 5.2, no. 4/5 (2015): 100–118.

http://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1855&context=fac_articles.

Stremlau, Rose. Sustaining the Cherokee Family: Kinship and the Allotment of an Indigenous Nation. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Sturm, Circe. Blood Politics: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 2002.

———. "Race, Sovereignty, and Civil Rights: Understanding the Cherokee Freedmen Controversy." Cultural Anthropology 29, no. 3 (2014): 575–598.

https://culanth.org/articles/751-race-sovereignty-and-civil-rights-understanding.

Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. New York: Viking, 2007.

Web

Genetin-Pilawa, C. Joseph. "Late 19th-Century US Indian Policy." Oxford Research Encyclopedias of American History. Oxford University Press. 2016.

http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-312.

"History: Cherokee Nation." Cherokee Nation All Rights Reserved. Accessed on June 20, 2017.

http://www.cherokee.org/About-The-Nation/History.

"Learn about the Cherokee Government and Our Proud History." Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Accessed on June 20, 2017.

https://ebci.com/government/.

Primary Documents in American History: Indian Removal Act. Library of Congress. 2017.

https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Indian.html.

Records Pertaining to Cherokee Removal, 1836–1839. US National Archives and Records Administration. 2016.

https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/cherokee-removal.html.

Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730–1842. Digital Library of Georgia, GALILEO. 2014.

http://dlg.galileo.usg.edu/CollectionsA-Z/zlna_information.html?Welcome&Welcome.

Similar Publications

| 1. | William Safran, "Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return," Diaspora 1 (July 1991): 83–99; Michele Reis, "Theorizing Diaspora: Perspectives on 'Classical' and 'Contemporary' Diaspora," International Migration 42 (June 2004): 41–60; Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997); Rogers Brubaker, "The 'Diaspora' Diaspora," Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (January 2005): 1–19; Paul Burke, "Indigenous Diaspora and the Prospect for Cosmopolitan 'Orbiting': The Warlpiri Case," Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 14 (August 2013): 304–7; James Clifford, "Indigenous Articulations," Contemporary Pacific 13 (Fall 2001): 470–72, 478–79; Robin Delugan, "Indigeneity across Borders: Hemispheric Migrations and Cosmopolitan Encounters," American Ethnologist 37 (February 2010): 41–2. |

|---|---|

| 2. | William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983); Keith H. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996); James Taylor Carson, "Ethnogeography and the Native American Past," Ethnohistory 49 (Fall 2002): 765–784; Robbie Ethridge, Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). |

| 3. | Andrea L. Smith and Anna Eisenstein, Rebuilding Shattered Worlds: Creating Community by Voicing the Past (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 3–4, 11–13. |

| 4. | James Taylor Carson, "Cherokee Ghostings and the Haunted South," The Native South: New Histories and Enduring Legacies, eds. Tim Alan Garrison and Greg O'Brien (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 238–62. |