Overview

Andrew W. Kahrl reviews William E. O'Brien's Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015).

Review

In the years surrounding the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision, state legislatures as well as county and municipal governments in the US South hastily built new "colored" schools in a desperate attempt to convince federal courts that separate could be equal. White officials tried in vain to give the appearance of equality to spaces and institutions conceived and designed to engineer inequality. This included the "Great Outdoors." In Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South, a fascinating, deeply researched, and richly illustrated book, William O'Brien tells the story of segregated state parks and recovers a history that states have worked assiduously to erase. O'Brien's is the third book in the Library of American Landscape History's "Designing the American Park" series, a collection devoted to exploring aspects of North American park history which, as series editor Ethan Carr explains in the preface, "remain relatively obscure in proportion to their significance" (ix). One could scarcely imagine a more fitting subject for this series. State parks, O'Brien convincingly shows, became important battlegrounds in the legal and bureaucratic struggle over segregation. The history of these places offers new insights into the way states and localities utilized federal programs and dollars to bolster Jim Crow and extend its reach, the cautious approach and ambivalent attitude of New Deal-era agencies toward southern defiance of federal law, and the evolution of the NAACP's legal strategy for securing African Americans' civil rights.

Locations of state parks in the South highlighting facilities made available to African Americans between 1937 and 1962. Map by William O’Brien. Originally published in William O’Brien’s Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015). Image provided by author.

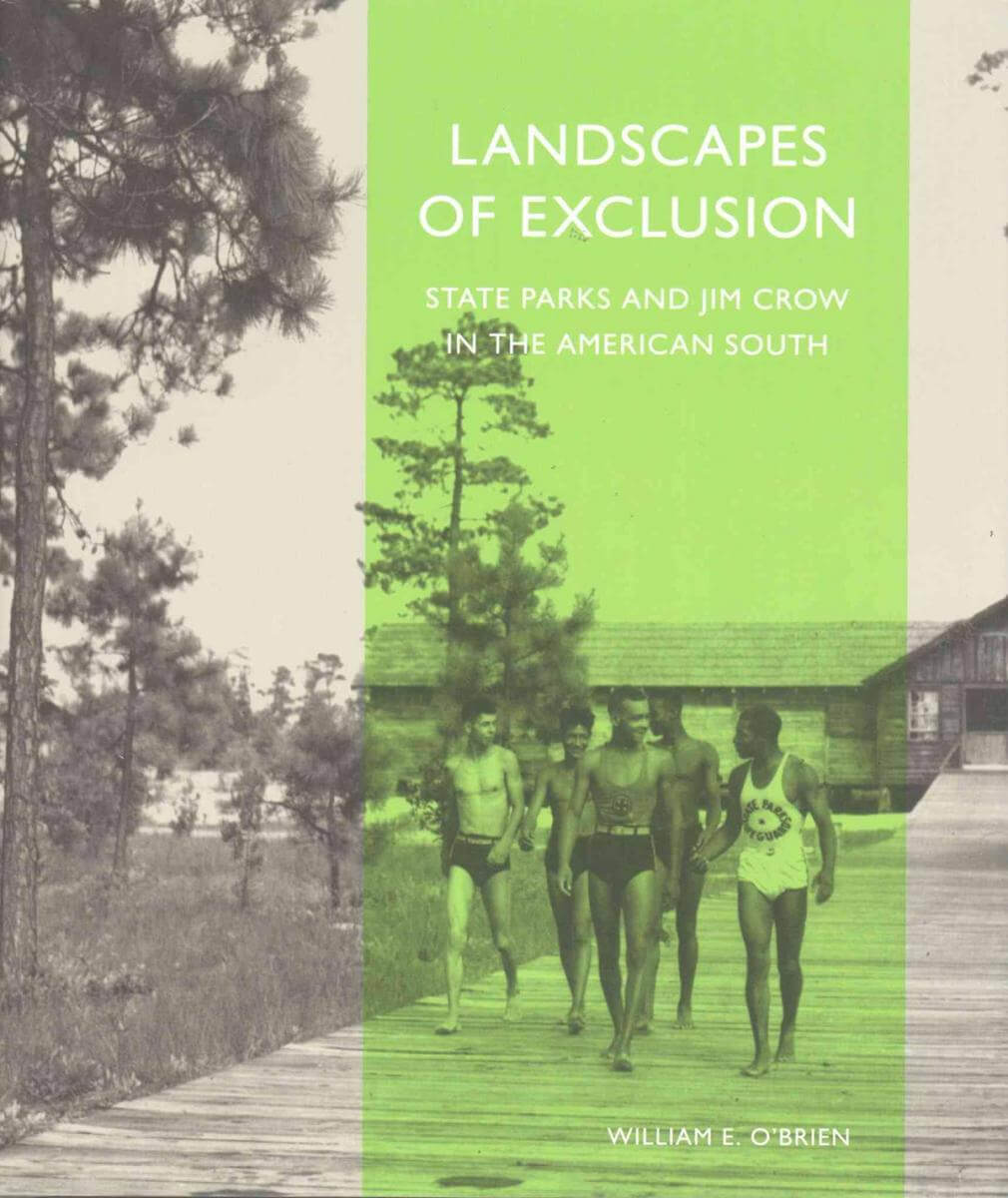

As O'Brien's work suggests, of all of the segregated facilities that dotted the South, few were more nakedly unequal or more clearly designed to inscribe white supremacy and black inferiority onto the built and natural environment than public parks. Without exception, African American outdoor accommodations were vastly inferior in size and quality, often located in remote, inaccessible areas, on land that formerly served as dumping grounds and mosquito-breeding spots. Providing black citizens separate spaces that approximated the outdoor experiences whites enjoyed at coastal beaches, interior lakes, and mountain parks was a practical impossibility. Even modest attempts by state and federal agencies to provide black citizens with decent parks in accessible locations succumbed to organized white opposition and bureaucratic indifference. Because of these gross inequities and the practical impossibility of state parks ever becoming separate and equal, the NAACP identified them as the "Achilles' Heel" of the Jim Crow system. By the 1950s, state parks had become one of the chief targets of civil rights lawyers in their fight to dismantle apartheid. During the 1960s, court-ordered desegregation rendered already sparsely-used Negro parks—once thought of as critical to the maintenance of white supremacy—deserted and superfluous. Today, physical evidence of Jim Crow's imprint on southern state parks is hard to find, except in the racial demographics of park users, which remain overwhelmingly white.

African Americans and whites still congregate separately in the newly integrated Lake Meer, Piedmont Park, Atlanta, Georgia, June 12, 1963. Photograph by Ken Patterson. Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library. Copyright Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Courtesy of Georgia State University.

While state parks predated the national park system, it was not until the 1920s that states began to take active measures to preserve natural landscapes and provide recreational resources. These efforts accelerated in the 1930s when states partnered with the National Park Service and New Deal agencies such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA). Typically, federal agencies acquired the land (through purchase or donation) and federal workers built the facilities before handing it over to states to operate. Between 1932 and 1942, the eleven states of the old Confederacy added 150 state parks, and excluded African Americans from nearly every one. While the National Park Service had an official nondiscrimination policy, typical of New Deal federal agencies it worked hard to avoid interfering with "local customs." As historian Ira Katznelson and others have written, southern Democrats used their control of Congressional committees to force virtually every significant piece of New Deal legislation to conform to—and, in the process, vastly expand—the power of Jim Crow. Bureaucrats in Washington learned to respect southern segregationists' power over the purse and avoid overt challenges to segregation.1Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright, 2013).

State Parks For Negroes Exhibit, State Fair Grounds, Richland County, South Carolina, 1958. Photograph by unknown creator, South Carolina State Commission of Forestry. Courtesy of Black and white negatives of South Carolina State Parks, 1934–1967 collection, Open Parks Network, Clemson University and National Park Service.

By the late 1930s, National Park Service officials, under pressure from civil rights organizations, encouraged southern states to provide some form of accommodation for African Americans. Reluctantly, states began to add "Negro areas" to existing state parks or designate new park sites for "colored" only. It wasn't until the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund (LDF) began filing lawsuits in the late 1940s that southern states attempted to "equalize" their park systems. It was a cynical strategy aimed at appeasing the courts and holding back civil rights. As O'Brien writes, "no state would pursue actual equalization" (15). Instead, they sought available lands deemed of "marginal economic value," "worthless for agriculture," that could be "purchased at a reasonable price" for Negro state parks (15).

Many "Negro parks" never made it off the drawing board. Those that opened had few visitors. Landscapes of Exclusion details how park planners perpetuated white racism. In South Carolina, for example, fearing that black bathers would pollute the water, planners eliminated possible sites for Negro parks in areas upstream from white parks (118). States did as little as possible; Negro park facilities usually existed in name only. Mississippi constructed a single park for black citizens, Carver Point on Grenada Lake. On paper, Carver Point was equal in size and provided the same amenities as its whites-only counterpart. But its remote location and the poorly maintained roads leading there made it inaccessible.

Charleston Negroes Seek Use of Lily-White Park. Published in the Memphis World, May 31, 1955, p. 6. Crossroads to Freedom Digital Archive, Rhodes College.

The few attempts by states to provide equivalent facilities for blacks generated white anger and hostility. When the CCC constructed two identical Recreational Demonstration Areas on Oklahoma's Lake Murray, local whites registered their opposition to a facility deemed "far too elaborate for Negroes" (54). The very idea of African Americans at leisure undermined the image of sweating black field hands laboring for whites.

Following Brown, the NAACP filed dozens of lawsuits to force the desegregation of parks. O'Brien details how, during the 1950s and 1960s, southern states resisted, and responded to federal court rulings declaring park segregation unconstitutional. Some states, such as Kentucky and West Virginia, quietly, bitterly, acceded to court rulings. Others waged campaigns of defiance. South Carolina opted to shut down its entire park system rather than desegregate. Still others concocted alternatives to public recreation. A sign of things to come, Georgia leased twelve of its parks to private operators. As Kevin Kruse and other historians have noted, the demise of legal segregation and African Americans' increased use of formerly segregated sites led whites to abandon public spaces in favor of private facilities. States and cities steadily withdrew support for public parks and recreation.2Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005).

Top, Jones Lake State Park, Bladen County, North Carolina, ca. 1940. Photograph by unknown creator, North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation. Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation Records collection, State Archives of North Carolina, North Carolina Digital Collections, State Library of North Carolina. Bottom, Jones Lake State Park Fishing Pier, Bladen County, North Carolina, August 25, 2013. Photograph by Flickr user Gerry Dincher. Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.0.

Southern states quickly got to work erasing evidence of their parks' Jim Crow origins. In Landscapes of Exclusion's final chapter, O'Brien explores the afterlife of Jim Crow state parks and makes the case for publicly acknowledging this history. Many of the Negro parks were simply shut down, sold off to private interests, or allowed to return to nature. Others were converted into privately owned and operated parks, or handed over to county governments. Several parks that once provided separate white and black facilities combined the two sites and removed all references to their segregated past. At these parks, O'Brien notes, the "footprints of segregated design remain" in the form of separate entrances, two sets of picnic and swimming areas, one invariably smaller and less attractive (152). In rare instances, states continued to operate formerly "colored only" parks under their original names and acknowledge in brochures and displays the park's racialized past. O'Brien found only three such parks still in operation today: Tennessee's Booker T. Washington and T.O. Fuller State Parks, and North Carolina's Jones Lake State Park (153).

O'Brien argues that state park agencies should do much more to acknowledge and reckon with the history and legacy of Jim Crow. As evidenced by the paltry numbers of black visitors to national parks today, many African Americans continue to feel unwelcome in such places. "[M]arking this racialized history can be potentially advantageous as a way of drawing new visitors. Most important, such actions help to preserve the national memory of African American struggles for justice" (155). The inclusion of Jim Crow in the public histories of state parks—much like the Equal Justice Initiative's effort to place a marker at every lynching site in the US—will serve as a reminder, especially to white park visitors, of a history of exclusion and ostracism written onto the natural landscape that continues to shape notions of race, understandings of nature, and encounters with the natural world.

About the Author

Andrew W. Kahrl is assistant professor of history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. He is the author of The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Recommended Resources

Text

Chafe, William H., Raymond Gavins, and Robert Korstad, eds. Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South. New York: The New Press, 2001.

Maher, Neil M. Nature's New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement. Oxford University Press, 2009.

O'Brien, William. "The Strange Career of a Florida State Park: Uncovering a Jim Crow Past." Historical Geography 35 (2007): 160–184.

Shumaker, Susan. "Segregation in the National Parks." In Untold Stories from America's National Parks, 15–36. Public Broadcasting Service, 2009.

Smith, Langdon. "Democratizing Nature Through State Park Development." Historical Geography 41 (2013): 208–223.

Taylor, Patricia A., Burke D. Grandjean, and James H. Gramann. "National Park Service Comprehensive Survey of the American Public 2008–2009." Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, July 2011.

Thompson-Miller, Ruth, Joe R. Feagin, and Leslie H. Picca. Jim Crow's Legacy: The Lasting Impact of Segregation. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014.

Vickers, Lu and Cynthia Wilson-Graham. Remembering Paradise Park: Tourism and Segregation at Silver Springs. University Press of Florida, 2015.

Web

"America's Parks." StateParks.com. 2017. http://www.stateparks.com/usa.html.

Golash-Boza, Tonya and Vlina Bashi Treitler. "Why America's National Parks Are So White." Aljazeera America. July 23, 2015. http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2015/7/heres-why-americas-national-parks-are-so-white.html.

Lear, Mike. "MU Researcher: Histories of Segregation, Racism Limit Blacks' Attendance at State, National Parks." Missourinet. June 21, 2016. http://www.missourinet.com/2016/06/21/mu-researcher-histories-of-segregation-racism-limit-blacks-attendance-at-state-national-parks/.

"North Carolina State Parks." North Carolina Digital Collections. State Archives of North Carolina and State Library of North Carolina. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/home/collections/nc-state-parks.

Repko, Melissa. "Segregated Parks Gone, but They Still Divide." The Dallas Morning News. February 15, 2015. http://interactives.dallasnews.com/2016/segregated-parks/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: Liveright, 2013). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2005). |