Overview

Patrick Vitale reviews Lindsey A. Freeman's Longing for the Bomb (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Review

It is a central contradiction of contemporary life that Americans have learned to coexist with mechanisms of human extinction.1The United States currently maintains an arsenal of 4,760 nuclear weapons, a decrease from its 1967 Cold-War-era high of 31,255. The use of only a fraction of these weapons would render vast quantities of the earth uninhabitable. Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, "US Nuclear Forces, 2015," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71, no. 2 (March 1, 2015): 107–19. We have, as E.L. Doctorow put it, become "people of the bomb."2Quoted in: Hugh Gusterson, Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 1. Of course, some love nuclear weapons more than others. Sociologist Lindsey Freeman introduces one population who embraced the bomb and today longs for its glory days: soldiers, scientists, engineers, and workers of the Oak Ridge National Atomic Laboratory.

Built as part of the Manhattan Project during World War II, Oak Ridge was one of three federal production sites housing workers and scientists who developed the atomic bomb. Freeman knows Oak Ridge from extensive ethnographic and archival research, and from personal experience. She was born there. Her grandparents lived there, and her grandfather was a soldier who trucked top-secret materials across the United States. Proud owner of a T-shirt that reads, "I am from Oak Ridge, I glow in the dark," Freeman has been thinking critically about her former home from a young age. Her deep immersion benefits readers and scholars as she addresses what sort of people Americans became as they embraced technologies of mass annihilation.

Finding something new to say about the history of the American nuclear weapons complex is not easy. Historians and social scientists have studied nearly every dimension. There are numerous histories of the Manhattan Project, biographies of key figures, and ethnographies inside and outside nuclear laboratories.3Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Vintage Books, 2005); Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986); Richard G. Hewlett and Oscar E. Anderson, The New World, 1939–1946: A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (Washington, DC: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1972); Gusterson, Nuclear Rites; Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Bruce Hevly and John Findlay, eds., The Atomic West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998); John Findlay and Bruce Hevly, Atomic Frontier Days: Hanford and the American West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011); Jon Hunner, Inventing Los Alamos: The Growth of an Atomic Community (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004); Paul Loeb, Nuclear Culture: Living and Working in the World's Largest Nuclear Complex (Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1986); Russell Olwell, At Work In The Atomic City: A Labor And Social History Of Oak Ridge, Tennessee (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004). Several studies explore the devastating effect of nuclear mining and testing on workers, indigenous peoples, and the environment.4Kate Brown, Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Sasha Davis, The Empires' Edge: Militarization, Resistance, and Transcending Hegemony in the Pacific (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015); Gabrielle Hecht, Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012); Joseph Masco, The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006); Peter van Wyck, The Highway of the Atom (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2010). Beginning with Elaine Tyler May's Homeward Bound and Paul Boyer's By the Bomb's Early Light, there are enough scholarly accounts of how the bomb rewrote the character of American life to stock the library of a fallout shelter for years.5Paul Boyer, By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985); Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988).

Given this exhaustive historiography, Freeman acknowledges that she did not write a "predatory book" that "devours" extant scholarship. Instead, her work fills an unstudied gap (4), emphasizing "Oak Ridgidness": "a particular cultural sensibility based on a utopian vision of nuclear science, a belief in the necessity of a nuclear America, and a sense of expertise, elitism, and specialness" (7). As Freeman shows, for more than seventy years, Oak Ridge residents have steadfastly maintained this Oak Ridgidness. Even as the utopic possibilities of nuclear science markedly declined, they retained a "nostalgic gloss" for the laboratory and the weapons it produces (7).

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory, just west of Knoxville, Tennessee, was one of three key sites, along with Los Alamos, New Mexico and Hanford, Washington, where the first atomic bombs were developed. While scientists, engineers, and workers at Los Alamos concentrated on bomb design and Hanford housed a massive factory that converted uranium into plutonium, Oak Ridgers refined uranium-238 into highly fissile uranium-235. The United States used this refined uranium in the bomb it dropped on Hiroshima.6Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

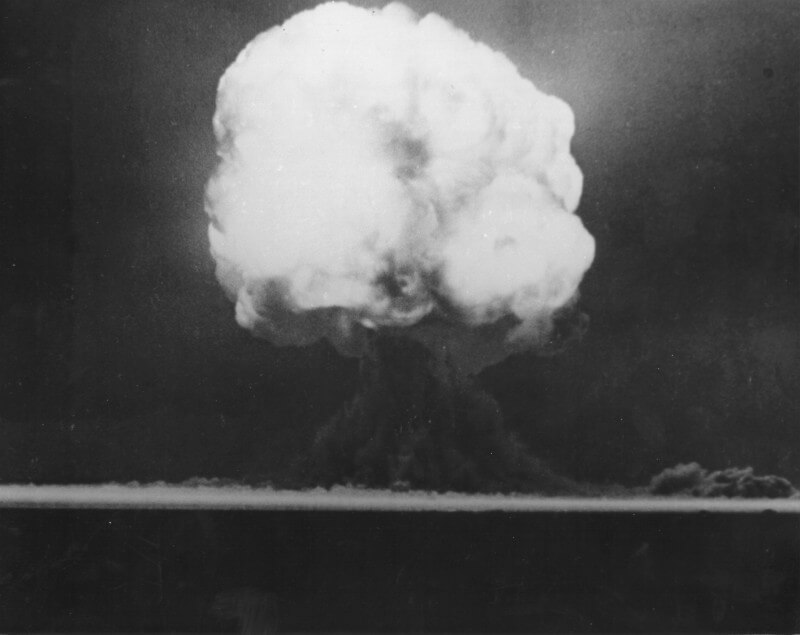

Trinity Test nuclear bomb 15 seconds after detonation, Alamogordo, NM, July 16, 1945. Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration/Nevada Field Office, www.nv.doe.gov/library/photos/photodetails.aspx?ID=51. Image is in public domain.

To develop the bomb, the Army Corps of Engineers constructed communities that would provide the necessary staffing and infrastructure for weapons production. In 1942, Army Corps officers travelled to East Tennessee, drawn to the supposedly uninhabited land, water and rail transport, and the abundant electrical power supplied by the Tennessee Valley Authority (17). At that time, the Clinch River Valley was home to the five small towns of Eliza, New Hope, Robertsville, Scarborough, and Wheat with a combined population of four thousand (17). In an act of what Freeman calls "magic geography," the Army Corps confiscated 59,000 acres of land and erased these five towns. It issued "requests to vacate" that granted residents as little as three weeks to relocate, explaining that "fullest cooperation will be of material aid to the War Department."7Hales, Atomic Spaces, 55. In place of the small towns, the Army Corps rapidly erected the city of Oak Ridge and the accompanying laboratory, which employed eighty thousand at its peak (1, 17, 19).

The authorized story of Oak Ridge's creation emphasizes the "myth of a peaceful and enthusiastic exodus" as patriotic residents gladly sacrificed their homes and farms for the good of the nation (26). In contrast, Freeman describes how the displaced unhappily packed into nearby towns, some forced to sleep in their cars, while landlords capitalized on increasingly scarce housing. Ultimately, most residents returned to their former land as tenants and employees of the federal government (20).

K-25 under construction, Oak Ridge, TN, ca. 1942. Photo by Ed Westcott. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

Peter Bacon Hales's Atomic Spaces (1997) exhaustively dissects the nuts and bolts of Oak Ridge's construction, so Freeman turns instead to its foundational mythology. Forty years before Oak Ridge's construction, "hillbilly prophet" John Hendrix foresaw the valley's transformation into a great factory that would manufacture a powerful weapon and help win the greatest war mankind had ever known. Freeman expertly unpacks how the federal government, scientists, and engineers fixated on the Hendrix story as a form of "atomic manifest destiny" that justified the displacement of thousands, the daily rigors of work at the laboratory, American militarism and imperialism, and the horrors unleashed by nuclear weapons (16). A video on display at the Smithsonian-affiliated American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge depicts a fictionalized John Hendrix explaining his vision:

It was God's plan to build a weapon to stop that war and there hasn't been another big one sense. What took place was an awesome miracle…. Since then God has allowed this nation to prosper and to help keep the rest of the world in order. So keep praying for this nation. Especially, for us to return to our Christian heritage on which we were founded. (32)

As Freeman explains, the story of Oak Ridge's transformation into a high-tech hub of nuclear engineers evokes the teleology of the American frontier as a justificatory myth. The development of nuclear weapons represented the latest example of America fulfilling its historic destiny. The pioneering scientists of the nuclear laboratory had neatly replaced the hardscrabble pioneers of Appalachia.

Living on the nuclear frontier, Oak Ridgers understood their home as "an island of culture, prestige, and intelligence" (37). The Army Corps hired the leading architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM) to design the town. SOM integrated cutting-edge elements of suburban design including curvilinear streets, cul-de-sacs, neighborhood units, and a greenbelt.8On the longer history of suburban planning see: Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (New York: Basic Books, 1987); Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); C. Topalov, "Scientific Urban Planning and the Ordering of Daily Life: The First 'War Housing' Experiment in the United States, 1917–1919," Journal of Urban History 17, no. 1 (November 1, 1990): 14–45; Marc A. Weiss, The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987).

Oak Ridge designers created residential neighborhoods intended to attract scientists and engineers not eager to relocate to rural Appalachia. In vague and bizarre terms necessitated by wartime security, SOM explained its development plan:

A plan not for any city but for a particular city, a city located at a particular point in the United States for good reason and a city living a particular sort of life because of its location and the reasons behind it… planned as a place of good living for people who are depended upon to do good work… For that reason the physical facilities that serve the people of Oak Ridge cannot be reduced to a few standard categories designed for the average man. (46)

To increase the site's appeal, the federal government provided such amenities as a Columbia University-designed school system, free healthcare, swimming pool, symphony, and extensive public transit.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, ca. 1930–1940. Postcard by Standard Souvenirs & Novelties, Inc. Courtesy of Digital Commonwealth.

Oak Ridge came to resemble other American suburbs. Just as the planners of New Deal housing legislation determined that racial segregation best facilitated stable housing markets, the planners of Oak Ridge agreed that accommodating existing social norms, including white supremacy, would best benefit the war effort. Oak Ridge social relations were decidedly retrograde. Its top scientists resided in well-equipped, detached homes in Knob Hill, colloquially known as Snob Hill, Brain Alley, or Little Westchester. Single, white women workers lived in monitored dormitories. Many of the tens of thousands of construction workers were housed in barracks and temporary trailers. The least-skilled crammed into squalid hutments (51).

SOM's original plan included a "negro village," but the Army Corps converted it to white housing. Instead the Corps created a rudimentary, segregated area of hutments for black workers that one observer described as a "modernized Hooverville" (56). Officials maintained gender segregation for black workers—black women lived in "the pen," an area circumscribed by electric fences and armed guards. Valerie Steel, a former Oak Ridge resident, described "total" segregation: "Blacks lived day in and day out under oppressive conditions. There were separate communities, cafeterias, recreational houses, churches, and water fountains, and blacks had to ride on the back of buses" (58). In 1950, after years of protest, the federal government built a black neighborhood in Gamble Valley, adjacent to the city dump and two miles from the nearest white housing (111). Journalist Joan Wallace described Gamble Valley as "the most deliberately isolated black community in the country." Freeman quotes several white Oak Ridgers who professed ignorance about the living conditions of its residents (112, 58).

Billboard encouraging secrecy amongst Oak Ridge workers, Oak Ridge, TN, ca. 1940s. Photo by Ed Westcott. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

The federal government encouraged Oak Ridgers to understand their livelihoods as contributing to the war effort. Even though most residents had no idea what purpose their work served, billboards, posters, and other propaganda warned them to remain tight-lipped. The local newspaper, the Oak Ridge Journal, ran a semi-regular editorial titled "silence means security" and its masthead reminded readers that it was "not to be taken or mailed from the area" (82). As the Cold War and the supposed threat of espionage grew, Oak Ridgers monitored neighbors for signs of disloyalty or weakness. Even Santa Claus was not above suspicion. Learning to live in Oak Ridge meant adopting a "culture of secrecy" that created loyalty and disciplined behavior.9Gusterson, Nuclear Rites, 68.

Elza gate entrance to Clinton Engineering Works, Oak Ridge, TN, ca. 1945. Photo by Ed Westcott. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Image is in public domain.

In 1949, the government announced plans to open Oak Ridge to the outside world. Many residents voiced opposition. At a town council meeting attended by two hundred, only seventeen voted to remove the municipal gates. In Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs recounts how residents had become accustomed to "stockade life" and "feared for their safety without the fence" (113). It was "a beautiful enclave that we didn't want to share," said one inhabitant to Freeman (113). On March 19 a small mushroom-cloud-inspired explosion severed a ribbon and visitors freely entered the town. During opening ceremonies, Tennessee governor Gordon Browning consoled residents that, even without the gates, "This unique but wide awake city is part of all of us without restrictions except where restrictions should be" (118).

In the final third of Longing for the Bomb, Freeman turns to the memorialization of Oak Ridge and its atomic history. Quoting local historian Bill Wilcox, she notes that fostering tourism becomes a way to "get folks to turn off the interstate" (139) and take in the sites of Oak Ridge such as the American Museum of Science and Energy and the Y-12 National Security Complex. She also examines the images of photographer Ed Wescott, for many years the only photographer permitted to document work and everyday life at the laboratory.

Top, A car drives past a banner advertising the Secret City Festival, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, June 11, 2015. Photograph by Adam Lau. Courtesy of Knoxville News Sentinel.

Bottom, Oak Ridge city employees Debbie Palmer, left, and Mike Brooks prepare the outdoor pavilion, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, June 2015. Photograph by Bob Fowler. Courtesy of Knoxville News Sentinel.

One of the most engaging narratives of Longing for the Bomb is Freeman's account of her Y-12 tour (open only to US citizens), which she attends during the annual, two-day, Secret City Festival. She listens from the back of the bus as the tour guide voices many of the book's key concerns: the wartime effort at Oak Ridge "proved that science can be moved from the laboratory to the battlefield. . . .The science was a miracle. The city itself was a miracle" (146). She hears that Oak Ridge today is the site of the "Headquarters for Homeland Security Technology Section." Stopping at the decommissioned X-10 graphite reactor, the guide observes that "the success of the Project during World War II was not something the nation could do today—the country has become too individualistic" (148). Alert to this "narrative of a selfish nation in decline" (148), Freeman notes that for visitors, Oak Ridge and its nuclear weapons are examples of both the decline and possibility of national progress. Freeman not only gets us thinking about Oak Ridge, but about parallels between this supposedly exceptional place and our own lives. She quotes Eudora Welty, that "one place comprehended can help us understand other places better" (xv).

I wonder whether Oak Ridgidness is really exceptional. Much of everyday life that took place there is familiar to most Americans: racism and segregation continue there, as they do throughout the nation. Freeman's account of the vigilant, but banal national security culture of Cold-War-era Oak Ridge seems similar to the "see something say something" consciousness of the "war on terrorism." Utopic faith in science has been shaken, but most Americans still believe that technology can save us from looming social and environmental perils. Today Oak Ridge has been eclipsed by other exclusive spaces for scientists and engineers, such as Cupertino, Mountainview, and Bethesda. Nonetheless, Oak Ridge remains an active monument to an abiding faith that compartmentalized science and expertise will deliver us into a lasting era of peace, security, and progress. Oak Ridge offers one of the clearest examples of how we have learned to see the means of destruction as our salvation.

About the Author

Patrick Vitale is a faculty fellow in the Draper Program at New York University. He is revising a book manuscript that examines the role of nuclear science and technology in the remaking and suburbanization of Pittsburgh during the Cold War.

Recommended Resources

Text

Brown, Kate. Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Gusterson, Hugh. Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Hales, Peter Bacon. Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Van Wyck, Peter. The Highway of the Atom. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2010.

Web

American Museum of Science and Energy. UT-Battelle and the Department of Energy. http://amse.org/

"Oak Ridge, TN." Voices of the Manhattan Project. Atomic Heritage Foundation and Los Alamos Historical Society. http://manhattanprojectvoices.org/location/oak-ridge-tn.

Taylor, Alan. "The Secret City." The Atlantic Photo. June 25, 2012. http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2012/06/the-secret-city/100326/.

The Photography of Ed Wescott. American Museum of Science and Energy. http://photosofedwestcott.tumblr.com/.

Y-12 History. Y-12 National Security Complex. http://www.y12.doe.gov/about/history/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | The United States currently maintains an arsenal of 4,760 nuclear weapons, a decrease from its 1967 Cold-War-era high of 31,255. The use of only a fraction of these weapons would render vast quantities of the earth uninhabitable. Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, "US Nuclear Forces, 2015," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 71, no. 2 (March 1, 2015): 107–19. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Quoted in: Hugh Gusterson, Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 1. |

| 3. | Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Vintage Books, 2005); Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1986); Richard G. Hewlett and Oscar E. Anderson, The New World, 1939–1946: A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (Washington, DC: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1972); Gusterson, Nuclear Rites; Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997); Bruce Hevly and John Findlay, eds., The Atomic West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1998); John Findlay and Bruce Hevly, Atomic Frontier Days: Hanford and the American West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011); Jon Hunner, Inventing Los Alamos: The Growth of an Atomic Community (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004); Paul Loeb, Nuclear Culture: Living and Working in the World's Largest Nuclear Complex (Philadelphia: New Society Publishers, 1986); Russell Olwell, At Work In The Atomic City: A Labor And Social History Of Oak Ridge, Tennessee (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004). |

| 4. | Kate Brown, Plutopia: Nuclear Families, Atomic Cities, and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Sasha Davis, The Empires' Edge: Militarization, Resistance, and Transcending Hegemony in the Pacific (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015); Gabrielle Hecht, Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012); Joseph Masco, The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006); Peter van Wyck, The Highway of the Atom (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2010). |

| 5. | Paul Boyer, By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985); Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988). |

| 6. | Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb. |

| 7. | Hales, Atomic Spaces, 55. |

| 8. | On the longer history of suburban planning see: Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (New York: Basic Books, 1987); Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); C. Topalov, "Scientific Urban Planning and the Ordering of Daily Life: The First 'War Housing' Experiment in the United States, 1917–1919," Journal of Urban History 17, no. 1 (November 1, 1990): 14–45; Marc A. Weiss, The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987). |

| 9. | Gusterson, Nuclear Rites, 68. |