Overview

In this photo essay, Lydia A. Harris presents facades and interiors of several homes in Collier Heights, a historic district in Atlanta, Georgia. All photographs by Lydia A. Harris.

Introduction

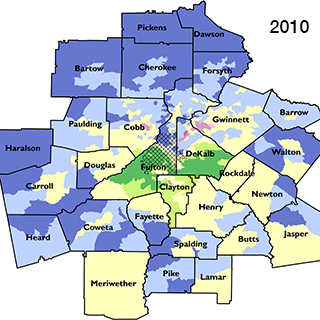

In August 2015, the Collier Heights home of Herman J. Russell (1930–2014), African American construction and real estate executive, came on the Atlanta market for $675,000. The listing video characterizes Russell's home as a hub for both real estate transactions, political strategy sessions, and community barbecues.1After two price reductions, as of January 2016, the house was listed at $497,000. See Phil W. Hudson, "Herman J. Russell's home hits the market," Atlanta Business Chronicle, January 8, 2016, http://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/news/2016/01/08/herman-j-russell-s-old-home-hits-the-market.html; Kimberly Turner,"House Envy: Andrew Young reminisces on Herman J. Russell's 1963 Home," Atlanta Magazine, January 20, 2016, http://www.atlantamagazine.com/homeandgarden/house-envy-andrew-young-reminisces-on-herman-j-russell-1963-home/. The founder of H.J. Russell & Co. was a key player in the city's racially-shifting midcentury real estate business and power structure. Collier Heights, originally a predominately white neighborhood in Atlanta’s southwest corner, would not have welcomed Russell when he founded his company at the height of Jim Crow restrictions in 1952. The 8,761-square-foot residence on 714 Shorter Terrace signals the hard work and commitment of businessmen and women, like Russell, who established residential and retail districts for Atlanta’s growing black middle class. In 2009, the National Register of Historic Places recognized Collier Heights as the first neighborhood developed, financed, designed, and constructed by African Americans for African American residents.2See Betsy Riley, "Collier Heights awarded Local Historic district status," Atlanta Magazine, May 16, 2013, http://www.atlantamagazine.com/civilrights/collier-heights-awarded-local-historic-district-status/; U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Collier Heights Historic District Application, NPS Form 10-900,OMB No. 1024-0018, received by NPS May 15, 2009, http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/sample_nominations/CollierHeightsHD.pdf.

As of 2016, Collier Heights is a neighborhood of approximately 1,700 single-family homes in 54 separate but interrelated subdivisions on over one thousand acres. Fleeing urban displacement, impoverished schools, and rampant segregation, African American residents moved to Collier Heights en masse between 1952 and the late 1960’s, redefining the area’s color line and populating a neighborhood important in the civil rights movement. Former residents include Martin Luther King Sr., Christine King Farris, and Ralph David and Juanita Abernathy.

Lydia Harris: Photographer's Statement

In 2010, I began taking portraits of homeowners in front of their Collier Heights houses using my 4x5 large format camera. After spending two years meeting with residents and making images of facades, I began conducting oral history interviews and taking photos inside neighborhood homes. These sessions became the 2015 book and photo exhibition, "The View of Collier Heights," staged in the Auburn Avenue Research Library Auxillary Gallery at Atlanta’s Hammonds House Museum.

For this Southern Spaces photo essay, I include "Facades," photos of the homeowners ("Faces"), along with several interiors ("Recreation Rooms" and "A Seat at the Counter") of Collier Heights homes. During Jim Crow, when owning a home was a civil rights victory unto itself, neighborhood residents made full use of their hard-won residences. These photographs suggest how facades and recreation rooms (with furniture, home design, objects, and décor) expressed one style of African American domestic life in midcentury Atlanta.

Facades

The home of Mr. Alfred and Dorothy Knox in the Royal Oaks Manor subdivision of Collier Heights, October 14, 2012. "This was a kind of remote area of the city when we first moved here," Knox, a businessman explains. "We were displaced by urban renewal. And although I kind of objected to being displaced, because I had a business there, and I had great plans for improvement in the community, south of the city here, but we lost all and moved here. And we are very glad that we moved here. Very pleasantly surprised to have such good neighbors." Knox, interview by author, May 13, 2013.

The home of Mr. Roger Mathews located in the Valhacha subdivision of Collier Heights, November 9, 2011.

The home of Mr. Charles and Dr. Lois Moreland in the Royal Oaks Manor subdivision of Collier Heights, October 12, 2013. The Morelands moved into their home in December of 1961.

The home of Dr. William B. Shropshire III and Dr. Marian Shropshire on Waterford Road in the Woodlawn Heights area of Collier Heights, November 14, 2011.

The home of native Atlantan Dr. Harvey B. Smith, who lives next door to the Shropshires, January 9, 2013. Smith was one of the original land buyers in the Woodlawn Heights Development Company, which built and developed significant portions of Collier Heights. He came to this neighborhood because there was a "great need for housing for people within my group, and there were few places you could find to go." Smith, interview by author, January 11, 2013.

The home of Alma and Albert Hayward in the Woodlawn Heights subdivision of Collier Heights. Top, under construction in 1962, and bottom, May 17, 2015. Historic image courtesy of the Haywards.

Recreation Rooms

Of the thirty-nine homes that existed in Royal Oaks Manor (a Collier Heights subdivision) in 1969, twenty-two included recreation rooms intended for "seated luncheons, dances, parties, receptions, fashion shows, games, relaxation, and television."3A considerable percentage of space was dedicated to leisure time, unlike the small houses in the original Collier Heights subdivisions that were built for middle class Americans. See Annie S. Barnes, The Black Middle Class Family: A Study of Black Subsociety, Neighborhood, and Home in Interaction (Lima, Ohio: Wyndham Hall Press, 1985), 74. Henry Herbert Bankston, a government worker and resident of Collier Heights, remembers, "I think about our getting together like we once did and it was basically because we did entertain in our basement. Or in our recreation area, that's what we called it. And that's where we had our parties, that’s where we had dances, and all, and meetings, in our basements. See, we can come in here and entertain in this living room, but that recreation room downstairs is where we came and had our little dances, where we had our club meetings, and so forth and so on. Most of these homes around here are equipped that way."4Henry Herbert Bankston, interview by author, April 12, 2012.

A Seat at the Counter

Faces

Alfred and Dorothy Knox, October 14, 2012.

Charles and Dr. Lois Moreland, October 12, 2013.

Dr. William B. Shropshire III and Dr. Marian Shropshire, November 14, 2011.

Dr. Harvey B. Smith, January 9, 2013.

Alma and Albert Hayward, May 17, 2015.

Constance Pruitt and her son John, April 6, 2012.

E. Gayle Barnett, January 10, 2013.

Brick by Brick

As Lorainne Hansberry writes in 1959’s A Raisin in the Sun, "we have decided to move into our house because my father—my father—he earned it for us brick by brick."5Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 148. For residents whose homes were built—brick-by-brick—by fellow African Americans, from conception to financing to development and construction, Collier Heights represents more than a hallmark of change. The neighborhood became a sanctuary where black Atlantans claimed a space of their own. As I return to the image of the Herman J. Russell home that begins this essay, my eye follows a stone path to the front door. As neighborhoods like Collier Heights experience new demographic shifts and historic homes go on the market, may we remember those who opened doors and paved the way.

About the Artist

Working in photography, video, and installation, Lydia A. Harris's art tackles situations of inequality and power dynamics. Her solo shows have included exhibitions at the Photographic Resource Center in Boston, the Hammonds House Museum/Auburn Avenue Research Library Auxiliary Gallery in Atlanta, and the Firehouse Center for the Arts in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Group shows have included exhibitions at the Fort Point Art Center, the Essex Art Center, the Griffin Center for Photography, the Museum of Fine Art Boston, The Light Factory’s 4th Juried Annuale in Charlotte, North Carolina, and the University of Maine Museum of Art Photo National 2011 where she received the director’s purchase award for "Hendrie." For more information, please visit the artist's website.

Recommended Resources

Text

Kruse, Kevin Michael. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Wiese, Andrew. Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the Twentieth Century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Web

Blau, Max. "Collier Heights Named Historic District by City Council." Creative Loafing (Atlanta), May 8, 2013. http://clatl.com/freshloaf/archives/2013/05/08/collier-heights-named-historic-district-by-city-council.

"Collier Heights Historical Advertisements" in "A Separate Peace: Collier Heights" by Betsy Riley. Atlanta Magazine, April 30, 2010. http://www.atlantamagazine.com/gallery/collier-heights-historical-advertisements/.

Georgia General Assembly. Senate Resolution 1276. "Collier Heights Community; Recognize." Sponsored by Senators Tate of the 38th, Fort of the 39th, Orrock of the 36th, Seay of the 34th and James of the 35th. 2013–2014 Regular Session. http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20132014/SR/1276.

Grant, Bradford. "By Design: Collier Heights—A 1950s Modernist Haven." in "By Design: African Diaspora Architectural News." International Review of African American Art. http://iraaa.museum.hamptonu.edu/page/By-Design.

Haines, Errin. "Atlanta's Collier Heights Seeks Historic Status." Seattle Times, October 4, 2008. http://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/atlantas-collier-heights-seeks-historic-status/.

Harris, Lydia A. "Collier Heights." LAH Studio. http://www.lydiaharrisphotography.com/links/.

Riley, Betsy. "A Separate Peace: Collier Heights." Atlanta Magazine, April 30, 2010. http://www.atlantamagazine.com/history/a-separate-peace-collier-heights1/.

Robinson, Jeffrey. NOMAtlanta. Interview by Garfield Peart. Recorded by StoryCorps. May 10, 2015. http://nomaatlanta.org/storycorps-additional-trailblazer-1/.

U.S. Department of the Interior. National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Collier Heights Historic District Application. NPS Form 10-900. OMB No. 1024-0018. Received by NPS May 15, 2009. http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/sample_nominations/CollierHeightsHD.pdf.

Similar Publications

| 1. | After two price reductions, as of January 2016, the house was listed at $497,000. See Phil W. Hudson, "Herman J. Russell's home hits the market," Atlanta Business Chronicle, January 8, 2016, http://www.bizjournals.com/atlanta/news/2016/01/08/herman-j-russell-s-old-home-hits-the-market.html; Kimberly Turner,"House Envy: Andrew Young reminisces on Herman J. Russell's 1963 Home," Atlanta Magazine, January 20, 2016, http://www.atlantamagazine.com/homeandgarden/house-envy-andrew-young-reminisces-on-herman-j-russell-1963-home/. |

|---|---|

| 2. | See Betsy Riley, "Collier Heights awarded Local Historic district status," Atlanta Magazine, May 16, 2013, http://www.atlantamagazine.com/civilrights/collier-heights-awarded-local-historic-district-status/; U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Collier Heights Historic District Application, NPS Form 10-900,OMB No. 1024-0018, received by NPS May 15, 2009, http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/sample_nominations/CollierHeightsHD.pdf. |

| 3. | A considerable percentage of space was dedicated to leisure time, unlike the small houses in the original Collier Heights subdivisions that were built for middle class Americans. See Annie S. Barnes, The Black Middle Class Family: A Study of Black Subsociety, Neighborhood, and Home in Interaction (Lima, Ohio: Wyndham Hall Press, 1985), 74. |

| 4. | Henry Herbert Bankston, interview by author, April 12, 2012. |

| 5. | Lorraine Hansberry, A Raisin in the Sun (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), 148. |