Overview

Richard Weyhing reviews Cécile Vidal's edited volume, Louisiana: Crossroads of the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

Review

|

In this impressive volume edited by Cécile Vidal a collection of historians seek to recover a "marginalized" past (16) within American history. Louisiana: Crossroads of the Atlantic World examines the dynamic societies of colonial Louisiana shaped by a succession of European empires over the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries before emerging as the very heart of the antebellum Deep South during the cotton boom of the 1820s.

The book's contributors argue that Louisiana's early history can only be understood by adopting an Atlantic perspective—one that considers its colonial pasts as the products of various historical forces from Europe, Africa, and the rest of the Americas that converged upon the Caribbean basin following the Columbian voyages of the 1490s. With its explicit geographic focus, the volume consciously adopts David Armitage's popular genre of "Cis-Atlantic history," which explores "particular places as unique locations within an Atlantic world and seeks to define that uniqueness as the result of the interaction between local particularity and a wider web of connections" (3). Louisiana, with its location in the geographic center of the Americas, its historical ties to French, Spanish, and British imperial projects, and its discourse of both cultural distinctiveness and interconnectedness, is an ideal subject for this approach. As an exercise in Cis-Atlantic history, the volume's "central hypothesis," as Vidal writes in the introduction, is that "Louisiana's relations with other regions of the Atlantic world, not only Africa, but also Europe and the rest of the Americas, played a fundamental role in the formation of its society and culture" (6).

|

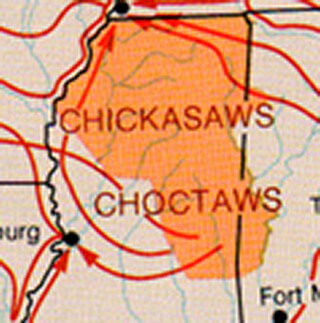

| "Carte de la decouverte faite l'an 1673 dans l'Amerique septentrionale," 1681. Earliest known map of the Mississippi River, by Father Jacques Marquette, but credited to Melchisédec Thévenot. The engraver was likely Jean Baptiste Liébaux. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, JCB Map Collection, 05266–1. |

Given this all-encompassing mission statement, some readers might expect the volume to explore a range of issues connecting Louisiana to the wider Atlantic world of which it was a part. If so, they will initially be disappointed since the collection of twelve essays is not quite as broadly conceived as suggested by the introductory remarks. Ten of the contributions ultimately dwell upon a theme familiar to historians of Louisiana after its incorporation into the American Republic: the "development and contestation of a racial order," as Vidal writes, that was central to Louisiana's earlier past as a colonial slave society that authorities hoped would emulate lucrative sugar producing islands in the Caribbean. Two essays serve as exceptions: Alexandre Dubé's piece concerning Louisiana's "plume"—the cadre of naval administrators who linked Louisiana with policy makers at Versailles during the French regime—and Sylvia Hilton's discussion of Spanish defense strategies during the long years of inter-colonial war in North America. Because it focuses upon the rise of slavery in "Lower Louisiana" during the eighteenth century, the volume leaves a host of other topics untouched and largely neglects the vast spaces of "Upper Louisiana" where colonial populations created thriving commercial and agricultural settlements in the Illinois Country and fostered complex—and often volatile—trading and diplomatic relationships with Indian peoples throughout the Mississippi River Valley. The lack of native perspectives in the volume is particularly unfortunate since much of what Europeans referred to as Louisiana remained in practice what historian Kathleen Duval refers to as a "Native Ground" well into the nineteenth century.1Kathleen DuVal, The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). A deeper engagement with the extensive enthnohistorical literature on native experiences in Louisiana would have enhanced the volume's appeal to early Americanists.

Despite these limitations, Louisiana offers valuable insights for students and scholars interested in its primary subject: the creation of racial hierarchies that enabled slavery to increasingly flourish here "before cotton" (204). Legal history has long been an important means of tracing the creation of these "orders" within slave societies, and many of the volume's essays could fit within this genre. They chart the various iterations of Lousiana's colonial slave codes, analyzing in rich, often imaginative detail, the aspirations and anxieties of authorities who attempted to construct and maintain categories of difference within the colonial population. Fittingly, Guillaume Aubert's piece opens the volume, illustrating how intensifying theological debates over the legitimacy of enslaving Christianized Africans within the wider "Catholic Atlantic" culminated in Louisiana's 1724 Code Noir. Aubert describes the law, which prescribed "inherent differences between white and black Catholics" (42), as "the most racially exclusive colonial law in the French Empire" (23). Other contributions, including those of Vidal, Sophie White, Mary Williams, and Emily Clark, elaborate on the many ways in which a "repressive legal and judiciary system" (15) drew upon past ideas and practices throughout the Atlantic world. This system not only circumscribed the meager legal rights of enslaved peoples, but also placed special emphasis upon policing the "intimacies" (123) of sex and marriage between blacks and whites that threatened to undermine the colony's socioeconomic and political order.

|

| Code noir, enacted by Louis XIV in 1685. 1743 re-edition courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Where the collection truly shines, however, is not in the dissection of colonial jurisprudence and its far flung influences, but in its exploration of the experiences of slaves (as well as free people of color) living under and against such systems—carving out unique spaces, whether economic, cultural, or sexual, in which they exercised the very agency that colonial officials and planters attempted to deny them. In their best moments, these essays transition into something resembling historical ethnography. White's contribution brings us into the underground economy of Louisiana's slaves who pieced together the various "theft cultures" (90–91) of West Africa and Europe to create networks of exchange in stolen goods that granted them access to the colony's cash economy and the power it afforded. Similarly, Jean-Pierre le Glaunec's essay presents slave communities as "crucibles of constant adaption" (121) in which peoples of varied African origins created networks of extraordinary fluidity in response to the constraints placed upon their lives. Finally, Mary Williams' and Emily Clark's pieces vividly depict the sexual and marital cultures of Lower Louisiana, as well as the racially mixed kinship networks engendered by slaves, free people of color, and whites that belied the edicts drawn up by the colony's successive regimes.

Taken together, the essays of Vidal's book offer a multifaceted amendment to the aging, but still debated, claims of Frank Tannenbaum's 1947 Slave and Citizen, which posited that, in comparison to their Protestant counterparts, the empires of Catholic France and Spain created more open systems of slavery in the Americas where racial hierarchies mattered less, and emancipation in the nineteenth century ultimately came much easier.2Frank Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947). By evaluating the strict codification of racial ideologies in the legislative councils of French and Spanish Louisiana and the myriad ways in which these codes could be manipulated and openly defied on the ground, Louisiana: Crossroads of the Atlantic World offers students and scholars of comparative slavery in the Americas a nuanced collection on Louisiana that extends to the Atlantic world. While scholarship on slavery in the colonial and early national periods has long emphasized the rise of the institution on the tobacco plantations of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Chesapeake or its subsequent expansion into the antebellum Deep South during the nineteenth century, Louisiana: Crossroads of the Atlantic World offers fascinating glimpses into worlds previously overlooked by many historians of the early American experience.

About the Author

Richard Weyhing is an assistant professor of history at State University of New York at Oswego specializing in early American history, Native American history, and history of the Atlantic World.

Recommended Resources

Text

Armitage, David. "Three Concepts of Atlantic History." In The British Atlantic World, 1500–1800, edited by David Armitage and Michael J. Braddick. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

Clark, Emily. Masterless Mistresses: The New Orleans Ursulines and the Development of a New World Society, 1727–1834. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

DuVal, Kathleen. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Hall, Gwendolyn Mido. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Hanger, Kimberly. Bounded Lives, Bounded Places: Free Black Society in Colonial New Orleans, 1769–1803. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997.

Ingersoll, Thomas. Mammon and Manon in Early New Orleans: The First Slave Society in the Deep South, 1718–1819. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999.

Spear, Jennifer M. Race, Sex, and Social Order in Early New Orleans. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Tannenbaum, Frank. Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947.

White, Sophie. Wild Frenchmen and Frenchified Indians: Material Culture and Race in Colonial Louisiana. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Web

Burnett, L. D. "Reading List: Transatlantic History in the Long Nineteenth Century." U.S. Intellectual History Blog, July 27, 2012. http://s-usih.org/2012/07/reading-list-transatlantic-history-in.html.

"The history of the transatlantic slave trade." International Slavery Museum, National Museums Liverpool, England. http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ism/slavery/.

"Lewis and Clark and the Indian Country: 200 Years of American History." The Newberry Library. http://publications.newberry.org/lewisandclark/.

"The Louisiana Purchase." The Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, The Thomas Jefferson Monticello. https://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/louisiana-purchase.

Transatlantic Studies Association. http://www.transatlanticstudies.com/.