Overview

Garrett Wright reviews Robin Beck's Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence in the Early American South (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Review

When Hernando de Soto's army of six hundred soldiers reached the middle Savannah River in 1540, arriving in what is today South Carolina and Georgia, they likely thought they had come to an abandoned wasteland. The desolation of this landscape must have presented a sore disappointment. The large indigenous populations, and their precious metals and labor, encountered by Spaniards in Tenochtitlan and Machu Piccu were nowhere to be found in the presumed wilderness. Yet the landscape was neither empty nor as depopulated as expedition accounts imply. Less than a century before de Soto's arrival, large urban centers peppered the American Southeast alongside smaller villages throughout what is now the region on either side of the border between North and South Carolina. And, less than one century later, multiethnic towns would again extend across the South.

In Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence in the Early American South, Robin Beck uses an interdisciplinary approach to gain new insights into this shifting social and political landscape. He uses the formation of the Catawba Nation from many smaller groups, known as coalescence, to understand larger changes in southeastern Native polities between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries. Beck's work complicates James Merrell’s monumental 1989 text on Catawba history, The Indians' New World.1James H. Merrell, The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989). The unearthing of new archaeological information, as well as historiographical developments in the study of chiefdoms, disease, and coalescence in the twenty years since Merrell's publication, necessitated revision of Catawba history. Beck answers that call with skill, weaving an archaeological and material analysis with sociological theory into a carefully crafted historical narrative.

Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence is organized into three sections corresponding to the titular eras of Native history. In the first, Beck considers chiefdoms from 1400 to 1650, demonstrating the centrality of maize surplus to the organization of the Mississippian political economy. Rather than portraying these chiefdoms as a reductive social category between tribe and state, he examines Mississippian chiefdoms as historically specific political economies involving hierarchical relationships among towns based on tribute and surplus. He then offers two Spanish expeditions' (de Soto's and Juan Pardo's) interactions with large chiefdoms to illuminate the complex political landscape that would soon be disrupted.

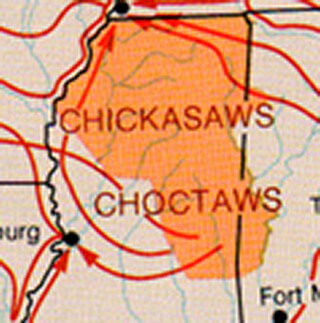

In the book’s second part, "Collapse," Beck aligns himself with recent scholarship on the role of epidemics in the creation of a "shatter zone"2Robbie Ethridge coined this term in "Creating the Shatter Zone: Indian Slave Traders and the Collapse of the Southeastern Chiefdoms," in Light on the Path: Essays in the Anthropology and History of the Southeast, edited by Thomas J. Pluckhahn and Robbie Ethridge (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006) to describe the seventeenth century demographic and cultural crisis that occurred in the Eastern Woodlands due in part to the increasing confluence of Native and European economies through the cross-cultural trade of people and furs. Though other scholars, such as Eric Wolf and Richard White, have situated similar crises within the global economy, Ethridge offers a unifying framework and vocabulary to understand this crisis as it unfolded in the Southeast and elsewhere. For more applications of the term see, Robbie Ethridge and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, eds., Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Robbie Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540–1715 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). in the midwestern and southwestern regions once controlled by Mississippian chiefdoms. He rejects the primacy of disease in the collapse of chiefdoms, instead using European traders’ accounts and limited archaeological evidence to emphasize the mid-seventeenth-century intrusion of "stranger Indians" (the Westos and Occaneechis) who used their military expertise and European firearms to capture slaves. In a world shattered by the combination of disease and the raids of such "strangers," Beck argues, the region near the lower Catawba River offered "relative shelter" due to its thin population density (135). The fear and violence that characterized the post-Mississippian Native landscape altered political relationships between groups. Defense and safety trumped surplus and hierarchy, and new alliances formed between groups such as the Waxhaws, Esaws, and Sugerees in the lower Catawba based on the common experience of suffering at the hands of the Westos and Occaneechis.

In "Coalescence," the book's final section, Beck surveys the eighteenth century chieftaincies that emerged from the shatter zone. Like other scholars, he understands the Yamasee War (a conflict from 1715 to 1717 between various Indian groups and South Carolina settlers) as a kairotic moment in the southeastern Indian slave trade and Indian-European relations. Beck is not concerned with the war itself as much as its effects on the political economy of Native polities in the Carolina Piedmont. The war virtually ended European dependence on Indian slaves provided by the Westos and Occaneechis, resulting in increased importation of African slaves. This shift from Indian to African labor also reduced the violence and instability that plagued Indians such as the Waxhaws and Esaws in prior decades and allowed for the creation of new chieftaincies that were nearly as large as their Mississippian precursors, but which were not grounded in a tribute-based hierarchical relationship between towns. Instead, because the political economy of Native nations in the Southeast now depended on commodities rather than surplus, power was less stable and required constant negotiation with other Indian and European polities. Beck demonstrates that Catawba chieftaincies were no less complex than their Mississippian counterparts, but were structurally different.

Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence in the Early American South offers a fresh perspective on Native historiography and provides a framework for similar studies of political change via "colonial entanglement" (1). Beck relies extensively on William Sewell, Jr.'s sociological theory of structure and event – in which normative principles and available resources can transform a group’s social organization (or structure), just as a group’s social structure can in turn constrain or expand its guiding principles and access to resources.3William H. Sewell, Jr., The Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Applying Sewell to the Catawbas affords Beck a fresh approach to questions of Native historiography. In applying social theory to coalescence, Beck argues against "clumsy" and reductive concepts of social and cultural change and instead uses structure to link fifteenth and eighteenth century Native political economies (10). Although these structures were fundamentally altered, they were based on familiar schemas and resources which allows their interpretation as similar structural polities rather than unique societies or cultures.

Sewell's theorized connection between resource management and social structures also allows Beck to approach coalescence in terms of changes in the political economy. He argues that the most significant change between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries was a shift from a political economy based on maize surplus, which in turn created hierarchical relations between villages and resource centers, to one based on firearms, slaves, and hides, which was exacerbated by the intrusion of European markets in Virginia and South Carolina. Beck is careful not to overstate the influence of Europeans and their trade goods and instead suggests that, while this new political economy made the previous surplus-based structure untenable, it also created new opportunities for power and wealth. In framing social change in this way, Beck is able to demonstrate the impact of Native Americans on their social structures as well as the limits placed on indigenous peoples and Europeans by the new political economy.

Beck's "eventful" approach roots Catawba coalescence in contingency, as he recognizes the unpredictability of structure-altering events. He identifies the migration of Indians from the north and access to European markets as the events fomenting titular collapse and coalescence. His narrative is rooted, however, in southern Indians' responses to these events rather than the imposition of new structures. Coalescence becomes a process of internal nation building in response to structural changes, rather than a one-sided shift wrought by the intrusion of European capitalism.

Chiefdoms, Collapse, and Coalescence is a skillful reorientation of early southern history that places the Indian experience at the center. The Mississippian chiefdoms of the fifteenth century and the chieftaincies of the eighteenth century figure as importantly as those of the emerging societies of South Carolina and Virginia. As Beck powerfully demonstrates, the history of these European colonies cannot be fully understood without knowledge of their wider geographical context, including the slave trade and diplomatic negotiations with Indian chieftaincies. Catawba coalescence is more than American Indian history or southern history. The United States as we know it would not exist without the consequences and legacies of Robin Beck's reframing of this foundational narrative.

About the Author

Garrett Wright is a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His dissertation is an ethnohistory of the eighteenth-century Pawnees, Otoes, and Kansas, focusing particularly on their strategies to protect their homelands and maintain their position at the center of continental trade networks.

Recommended Resources

Text

DuVal, Kathleen. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Ethridge, Robbie and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall. Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Merrell, James H. The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Perdue, Theda. Slavery and the Evolution of Cherokee Society, 1540–1866. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1979.

Smith, Adam T. The Political Landscape: Constellations of Authority in Early Complex Polities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Web

Ayer Art Digital Collection. Newberry Library. http://collections.carli.illinois.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/nby_eeayer.

"Maps ETC: Early America 1400–1800." Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida. http://etc.usf.edu/maps/galleries/us/earlyamerica14001800/index.php?pagenum_recordset1=1.

Miller, Christopher L. "Change and Crisis: North America on the Eve of the European Invasion." The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/american-indians/essays/change-and-crisis-north-america-eve-european-invasion.

"Trail of History: Catawba Heritage." Central Piedmont Community College TV Online. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DvWT5eLbnzI.

Similar Publications

| 1. | James H. Merrell, The Indians' New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact through the Era of Removal (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Robbie Ethridge coined this term in "Creating the Shatter Zone: Indian Slave Traders and the Collapse of the Southeastern Chiefdoms," in Light on the Path: Essays in the Anthropology and History of the Southeast, edited by Thomas J. Pluckhahn and Robbie Ethridge (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006) to describe the seventeenth century demographic and cultural crisis that occurred in the Eastern Woodlands due in part to the increasing confluence of Native and European economies through the cross-cultural trade of people and furs. Though other scholars, such as Eric Wolf and Richard White, have situated similar crises within the global economy, Ethridge offers a unifying framework and vocabulary to understand this crisis as it unfolded in the Southeast and elsewhere. For more applications of the term see, Robbie Ethridge and Sheri M. Shuck-Hall, eds., Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Robbie Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw: The European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540–1715 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). |

| 3. | William H. Sewell, Jr., The Logics of History: Social Theory and Social Transformation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). |