Overview

In this review essay, Valérie Loichot visits Kara Walker's installation: A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby.

Review

|

| frozen, photograph inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, June 6, 2014. Photograph by Eric Konon. Courtesy of Eric Konon. |

Oh ye who at your ease

Sip the blood-sweeten'd beverage—Robert Southey, Poems of the Slave Trade, Sonnet III1Robert Southey, The Poetical Works of Robert Southey (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1839), 110.

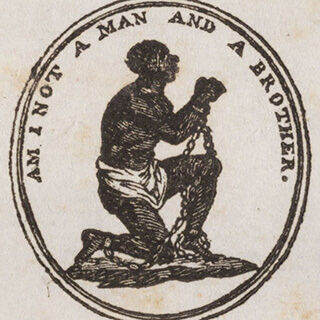

Nothing expresses more viscerally our blood-stained appetite for sugar than Kara Walker's installation, A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby.2Kara Walker, A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, May 10–July 6, 2014, Brooklyn, New York: Domino Sugar Factory. From Robert Southey, to Voltaire, to Victor Schoelcher, to Aimé Césaire, abolitionists, philosophers, and poets alike have used the trope of blood to denounce the dehumanizing system of slavery. The force of the metaphor resides in the fact that blood in sugar was also quite literal. Unpaid or exploited laboring humans left their blood, sweat, fingers, hands, and ultimately, lives, in the plantation machinery of sugar-cane slavery and sugar processing as though in a sacrifice devoid of sacredness and rituals. French philosopher Claude-Adrien Helvetius proclaims in 1758 "There is no sugar barrel that reaches Europe without stains of human blood."3"Il n'arrive point de barrique de sucre en Europe qui ne soit teinte de sang humain." Claude-Adrien Helvétius, Œuvres Complètes, Vol. 1 (Paris: Lepetit, Editeur, 1777), 25. Author's translation. An abolitionist movement in the 1780s calls itself "Blood Sugar" on the ground that "sugar cane was fertilized with the blood of African slaves."4Jody Dunville, "Blood Sugar," accessed June 30, 2014, http://web.utk.edu/~gerard/romanticpolitics/bloodsugar.html. On the "blood sugar" topos in Coleridge's 1795 lecture on the slave-trade and Southey's 1797 sonnets, see Timothy Morton, "Blood Sugar," in Romanticism and Colonialism: Writing and Empire 1730–1830, ed. Tim Fulford and Peter J. Kitson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 87–106. Also consult anthropologist Sidney Mintz's seminal Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin, 1985). Visual and installation artist Kara Walker herself, in an interview with Audie Cornish on National Public Radio, asserts: "Basically, it was blood sugar . . . like we talk about blood diamonds today, there were pamphlets saying this sugar has blood on its hands."5Audie Cornish, "Artist Kara Walker Draws Us Into Bitter History With Something Sweet," National Public Radio, May 16, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.npr.org/2014/05/16/313017716/artist-kara-walker-draws-us-into-bitter-history-with-something-sweet.

|

| Sugar Sublime: Kara Walker, Domino sugar, photograph inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, May 31, 2014. Photograph by Several Seconds. Courtesy of Several Seconds. |

"Blood Sugar," the title of my review, is also meant in its medical sense since one of the ravages of the sugar industry is the diabetes epidemic in the world's sugar-producing and consuming regions.6 In sugar cane producing French Overseas Departments—Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Reunion—the incidence of diabetes is twice as high as in continental France. "Le Diabète Explose en France: 2 Fois Plus de Diabétiques dans les Dom-Tom Qu'en Métropole," Docbuzz: L'Autre Information Santé, November 13, 2010, accessed July 2, 2014, http://www.docbuzz.fr/2010/11/13/123-le-diabete-explose-en-france-2-fois-plus-de-diabetiques-dans-les-dom-tom-qu%E2%80%99en-metropole. For the diabetes epidemics in the Caribbean, also see Ludmilla F. Wikkeling-Scott, "Addressing Diabetes, A Regional Epidemic in Caribbean Populations," June 5, 2012. Type 2 diabetes also has such prevalence in the US South that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention coined the term "Diabetes Belt": Melissa Healy, "Diabetes Belt: American South Gets More Health Notoriety," Los Angeles Times, March 8, 2011, accessed June 30, 2014, http://articles.latimes.com/2011/mar/08/news/lat-diabetes-belt-20110308. Exhibited at the decaying Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn from May to July 2014, Walker's monumental installation, organized on the occasion of the demolition of the Refining Plant,7The Domino Sugar Factory will be demolished in August 2014. The operating New York area Domino factory is located in Yonkers. Before the demolition, the "Marvelous Sugar Baby" will be melted down. Some of the resin figurines will be salvaged for museum exhibits. For the recollections of Robert Shelton, who worked on the floor of the Domino factory for twenty years see Vivian Yee, "2 Jobs at Sugar Factory, and a Lump in the Throat," New York Times, July 5, 2014, accessed July 5, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/05/nyregion/recalling-sticky-hot-job-before-old-domino-sugar-factory-falls.html. is dedicated to "the unpaid and overworked artisans who have refined our sweet tastes from the cane fields to the kitchens of the New World."8Writing on the wall of the exhibit entrance at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, New York. The exhibit consists of a gigantic West Indian, African, or African American mammy-sphinx, who could evoke any part of the global plantation South, made out of eight tons of confectionery sugar coated over a foam structure, and of life-size sculptures made out of molasses-covered resin. The exhibit offers no flyers, captions, or explanations, only a release form informing us that we enter the building at our own risk.9On the sanitary and safety state of the building at the time of the exhibit, see Claire Voon's "How are they Keeping Rats Off Kara Walker's Sugar Sculptures?," Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & Its Discontents, June 10, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://hyperallergic.com/130365/how-are-they-keeping-rats-off-kara-walkers-sugar-sculptures. A few volunteers answer questions of wandering visitors but overall we are left to draw our own conclusions.

When my friend and I visited the installation on June 13, 2014, the sky had turned slate black on one side of the industrial, decrepit, and gentrifying Williamsburg cityscape.10I am grateful to my friend and colleague, Professor Naïma Hachad, who helped me brainstorm during and after the exhibit and enriched this piece with her insights. We ran towards the building to escape an approaching downpour, powerful winds, and raging storm. We passed more than two hours inside, waiting for the storm to ease and for the water puddles blocking the exit to subside. The installation strongly intertwines with the factory, the city, the elements, and the environmental conditions and history that have shaped it. Over time, sugar has built up on the warehouse rafters and walls. Through sugar, the factory and Walker's art enter a symbiotic relationship, not only environmental but deeply historical. "This dank building," writes Jerry Saltz in his review of the installation, "where layers of history are caked on the walls with molasses, this place where brown sugar was turned white, multiplies the lurking meanings in Walker's work."11Jerry Saltz, "Kara Walker Bursts Into Three Dimensions, and Flattens Me," Vulture, May 31, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.vulture.com/2014/05/art-review-kara-walker-a-subtlety.html.

Only scarce natural light enters the building through narrow tainted windows and creases of the roof and walls. Humidity and darkness make it feel like entering a cave. As our eyes adapt, figures of black cherubs become visible. I turn my face to the right and see the gigantic marvelous Sugar Baby as if lit up from within like a powerful neon light, or a bright cinema screen filling the room almost to the ceiling. The first impression is of sharp contrasts between black and white, a statement on binaries created by the structure of slavery on which sugar production depended. Slowly, stains and pools of yellow and red appear.

|

| Get Me Before I'm Gone, photograph inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, May 31, 2014. Photograph by Several Seconds. Courtesy of Several Seconds. |

|

| approach, photograph inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, June 6, 2014. Photograph by Eric Konon. Courtesy of Eric Konon. |

Simultaneous with its visual spectacle, the installation greets our hearing and smell. Standing by the entrance closing our umbrellas and drying the bottoms of our dripping pants, we listen to the entering crowd: a mixed humanity of international tourists, locals, white and black visitors, children, art students, and elderly couples. They enter running into the grotto to escape the storm and drafty winds. Passing the threshold, their mouths gape in a unanimous "wow." The wows multiply and echo with each other, sometimes marked with awe, admiration, surprise, or horror. Sugar Baby is something as yet unseen in its scale, beauty, and monstrosity. The "wow" effect created by art, the monstrous beauty of the installation, the lightning making its way through the creases and narrow windows, and the blasts of thunder shaking the walls evoke the history of slavery.

Like naïve Hansel and Gretel, we seek shelter and sugar. Walker describes her work as a "confection": "Kara Walker has confected a Subtlety."12"Creative Time presents Kara Walker's A Subtlety," accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/. The artist is a pastry chef, a candy-maker, a sugar worker. Confectionery "is the art of creating sugar-based dessert forms, of subtleties."13"Confectionery," Wikipedia, accessed June 30, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confectionery. Exhibit chief curator Nato Thompson explains that subtleties are "sugar sculptures that adorned aristocratic banquets in England and France in the Middle Ages, when sugar was strictly a luxury commodity. These subtleties, which frequently represented people and events that sent political messages, were admired and then eaten by the guests."14Nato Thompson, "Curatorial Statement," accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/curatorial-statement/. The title and subtitle of the exhibit make perfect sense, until we experience their deep irony and the cruelties of the situation.

At first, we smell the scent of sugar familiar as confectioned sweets and candy. One visitor puts her nose to one of the figures. "At least it smells good," she says. But it only takes a few minutes to whiff the acrid stench of old sugar, a smell like that of meat or flesh rotting in the trashcan in the back of a restaurant on a hot afternoon. The sweet rancid air mixes with urine and corroding iron. Suddenly, we're lost characters in a Grimm tale.

|

| Wall text for Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, May 18, 2014. Photograph by Ann Hilton Fisher. Courtesy of Ann Hilton Fisher. |

Kara Walker, confectioner in chief, offers us the indigestion of the greedy act of consuming sugar for centuries. She turns into an avenger swallowing the public in her den for a little while and serving us a slice of history and a lesson in humanity. The invitation on the entry wall presents the exhibit as a confection made to please our taste and consumption. But it is against the rules to taste the sugar—no confectionery samples are offered at the end of the show—and the sugar is stinky and inedible. The exhibit stirs a reflex of nausea rather than hunger, an indigestion created by our consumption of sugar made possible by our exploitation of fellow humans. This luxury turned into necessity changed the course of human history, driving colonization of tropical zones, chattel slavery, indentured labor, and glucose illnesses.

I now need to go slow. I cannot rush to the enormous woman sphinx. I have to take my time in fear of what I will find.

Meandering wingless African cherubs pave the way to the monstrous and marvelous Sugar Baby. These five-feet tall black children, enlargements of collectibles, which could be found at the front door of a white southern home or sugar plantation, signifying "Southern hospitality," carry bananas or food in baskets.15"Walker went down a rabbit hole of sugar history, at one point stumbling on some black figurines online—the type of racial tchotchkes that turn up in a sea of mammy cookie jars," Audie Cornish, "Artist Kara Walker Draws Us Into Bitter History With Something Sweet," National Public Radio, May 16, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.npr.org/2014/05/16/313017716/artist-kara-walker-draws-us-into-bitter-history-with-something-sweet. The cherubs' sweet smiles, apple cheeks, and potbellies merge into the most terrifying part of the installation. Two months into the exhibit, the statues have changed, deteriorated, or disintegrated. A majority of the figurines are made of resin covered with molasses. The molasses cherubs, made of a viscous and dark by-product of cane refining, stand in sharp contrast with the white and powdery confectionary sugar of the sphinx. The crumbling molasses sculptures each weigh four hundred pounds: surprising for their true-to-life size. Kara Walker threw broken body parts and remains into the fruit-bearing baskets of their surviving brothers. The offering of food turns into an offering of human flesh, gesturing that sugar production and consumption are acts of cannibalism. My 2013 book The Tropics Bite Back was an effort to demonstrate that the image of the cannibal was projected onto Amerindians or Africans to dehumanize them.16Valérie Loichot,The Tropics Bite Back: Culinary Coups in Caribbean Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). See also Mimi Sheller's Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (London: Routledge, 2003) and Jack D. Forbes's Columbus and Other Cannibals (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008). Walker's installation makes clear that the true cannibalism was the machinery of colonization and enslavement.

|  |

| Two photographs of a child carrying a basket inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, 2014. Photograph on left by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. Photograph on right by B. C. Lorio. Courtesy of B. C. Lorio. | |

The molasses children who have suffered the most have stumps for limbs, tumorous skulls, gnawed mouths, empty eye sockets, and metal bars sticking out of their trunks. Blood- and pus-resembling liquid oozes from their groins as if they have been maimed by rape or castration. They resemble Emmett Till in the casket left open by his mother Mamie Till,17See, for instance, Devery Anderson, Emmetttillmurder.com, accessed June 30, 2014. or the raped and tortured figures of Walker's silhouette work.18See Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw's Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004). Transforming, the boys' flesh has gained pustules, mold, rot, and sandy growths,19Walker's installation resembles in its evolution Jason deCaires Taylor's underwater sculptures (accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.underwatersculpture.com/sculptures). However, while Taylor's sculptures' evolution with their coral environment conveys rejuvenation, Walker's art's alliance with the industrial site evokes degeneration. provoking a troubling confusion between human bodies, raw flesh,20For Hortense Spillers, the reduction to bare flesh is the condition of enslaved Africans. The critic reads the marking of the flesh of the New World African woman, of the "seared, divided, ripped-[apart], riveted to the ship's hole, fallen, or 'escaped' overboard," as a cultural text whose marking and branding "transfers from one generation of the other." See Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 206–207. the vegetal product of sugar cane, and the dilapidated metallic and stone surroundings of the warehouse. In Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett interprets American culture as marked by "hyperconsumptive necessity," by "thing-power" or "vitality": "the capacity of things—edible, commodities, storms, metals—not only to block the will and designs of humans but also to act as quasi agents of forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own."21Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 5, viii. In Bennett's sense, Kara Walker's creation is representative of slavery, but also of our generalized excess and hyperconsumption, in which organic and inorganic (human, animal, metal, and meteorological) coexist and co-act in confusion and enmeshment.

|  |

| Closeup of a child sculpture inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, June 13, 2014. Photograph by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. | A child sculpture inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, June 13, 2014. Photograph by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. |

In the complex game of lights and shadows at the Domino Factory, we see our reflections in pools of sugary water: we are part of this story, this history, either as culprits, victims, or consumers. We are part of this womb-machine that contains and shapes us in our modernity.22For Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, the hold of the slaveship, the slave plantation and its machinery constitute "bellies of the world," functioning at once as expelling guts and sheltering womb. See my Orphan Narratives for a discussion of Glissant's ambivalent bellies of the world: Valérie Loichot, Orphan Narratives: The Postplantation Literature of Faulkner, Glissant, Morrison, and Saint-John Perse (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). For Cuban writer Antonio Benítez Rojo as well, the sites of slavery and exploitation are also the wombs of modernity without which the industrialized world would not have been born. The Brooklyn Domino Sugar Refinery, established in its Williamsburg, New York, location in 1882, was the largest sugar refinery in the world, hence, a major belly of the world. Thompson explains that "The Domino Sugar refinery is certainly an integral part of the story of sugar. Built by the Havemeyer family in 1856, by 1870 it was refining more than half of the sugar in the United States, producing over 1,200 tons of the sweet stuff every day." See Thompson, "Curatorial Statement." Our bodies reflecting in the rain water pools mixed with resin and sugar by-product remind us of the mirroring, forever implicating, scene of the lynching of Joe Christmas in Faulkner's Light in August: "For a long moment [Joe Christmas] looked up at them with peaceful and unfathomable and unbearable eyes . . . upon that black blast the man seemed to raise soaring in their memories for ever and ever. They are not to lose it, in whatever peaceful valleys, . . . in the mirroring faces of whatever children they will contemplate old disasters and newer hopes."23William Faulkner, Light in August (New York: Vintage International, 1990), 465. Our reflections on a rainy day in the pools emanating from the tortured molasses babies, makes us see ourselves in the exhibit. Walker's art demands an ethical response.

At last, I am about to face Sugar Baby. A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby. The woman sphinx has no proper name and is defined with common nouns referring to things, a recurrent way to misname in situations of slavery or oppression, such as Sapphire, Sweet Thing, Boy, Mammy, etc. The rarer, confectionary meaning of "subtlety" is overshadowed by our everyday use of the term that refers to something delicate, discreet, moderate, nice, refined, and tasteful. But there is nothing subtle about the scale, weight, enormity, exaggerated features, mouth, vulva, breasts, paws, backside, exaggerated brightness and whiteness of Sugar Baby. Subtlety acts as a euphemism of the sort used to describe the monstrosity of slavery, as the "peculiar institution." As for "marvelous," it evokes something exciting, wonderful, strange, astonishing, miraculous, or supernatural, conveying visitors to a spectacular show, whether otherworldly (as in the "marvelous land of Oz") or the freak show (as in the "marvelous contortionist").

|

| Rear of the Sugar Baby sphinx inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, New York, June 13, 2014. Photograph by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. |

"Sugar Baby" could evoke any love relationship in which the beloved is turned into sweetness, from Song of Songs24"Thy lips, O my bride, drop honey." Source: "Song of Songs, Chapter 4," The Complete Hebrew Bible, accessed June 30, 2014http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt3004.htm. to Billie Holiday's "Sugar (That Sugar Baby O'Mine)": "Sugar, I call my baby, my sugar . . . I'd make a million trips to his lips / If I were a bee / Because he's sweeter than chocolate candy to me / He's confectionery."25"Billie Holiday—Sugar," YouTube, accessed June 30, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_UajeQsQrRA&feature=kp. The intersection of sugar production, slavery, and sexual exploitation turns bitter wherever black and colored women become objects of sexual consumption, in a direct metonymic and metaphorical relationship with sugar. They became fodder for the fields and food for sexual appetites.

Nina Simone's "Four Women" denounces the association between the light-skinned black woman as an easy object of consumption: "My skin is tan / my hair is fine / My hips invite you . . . Whose little girl am I? / Anyone who has money to buy / What do they call me? / My name is Sweet Thing / My name is Sweet Thing."26 "Nina Simone—Four Women," YouTube, accessed June 30, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRmzQ39sXTQ. The monster Walker—or rather slavery—has created is the material realization of the effacing of a woman's body with the sugar it produced or signified. The "baby" of Walker's exhibit is also to be understood as the offspring: the monstrous child of slavery. The factory becomes the belly birthing that monstrosity.

As in the popular expressions "sugar daddy" and "honey pot," "Sugar Baby" might as well be "money baby" in the logic of the inextricable confusion between sugar, money, and sex that the economy of slavery built. In other words, Walker's creation is the materialization of the monstrous equation of human bodies with sexual and culinary commodities.

After detours and musings, I finally draw close to Marvelous Sugar Baby in all her size, brightness, whiteness, and imposing presence. That her eyes are closed—the sphinx awaiting to give the enigma—also puts the visitor in the position of the voyeur who can contemplate without the gaze of the spectacle staring back. This discomfort is particularly strong as we face the back of the statue on all fours with its sexual parts exposed. The offered large breasts with well defined areolas and nipples are available for the gazer to seize, like enslaved women's breasts were available for the enslavers' infants and toddlers. This reality is present from Toni Morrison's Beloved27"And they took my milk!" See Toni Morrison, Beloved (Knopf: New York, 1994), 19. In her Washington Post piece (McDonald, "Going to See Kara Walker's A Subtlety? Read These First," Washington Post, May 27, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/05/27/going-to-see-kara-walkers-subtlety-read-these-first/), Soraya Nadia McDonald gives a non-inclusive reading list of novels by Morrison, Maryse Condé, Jean Rhys, and Jamaica Kincaid, who have focused on similar issues. to Kara Walker's cut-paper silhouette art in her 2007–2008 exhibit "American Primitives."28On "American Primitives," see Grace Elizabeth Hale's "A Horrible, Beautiful Beast," Southern Spaces, March 6, 2008, accessed June 30, 2014, https://southernspaces.org/2008/horrible-beautiful-beast. On the politics and aesthetics of milk in Kara Walker, see Patricia Yaeger's "Circum-Atlantic Superabundance: Milk as World-Making in Alice Randall and Kara Walker," American Literature 78, no. 4 (2006): 769–798. Sugar Baby's sex is exposed as her behind is lifted up in an offering position while she is on all fours. While this speaks to the availability, the sexual enslavement and animalization of the black woman's body,29For another contemporary take on the trope, see Beyoncé Knowles's 2006 "Suga Mama" in which the star sings on what looks like a white sugar cube in a pose reminiscent of the Marvelous Sugar Baby's four-legged pose. Beyoncé as well takes an ironic twist on the image, bending gender roles as she begins the song dressed as a stereotypical providing "suga daddy" rather than a "suga mama": "And I've always been the type to take care of mine / I know just what I'm doing . . . Puttin' you on my taxes already, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah." See "Beyonce—Suga Mama," Vagalume, accessed July 27, 2017, https://www.vagalume.com.br/beyonce/suga-mama.html. and to the exhibition of black women's sexual organs attached or not to a body—see the famous case of Saartjie Baartman—it can also be seen as a lesson to visitors, or as a gesture of extreme affront. The exhibition of the female organs of sex and reproduction can also, as in Gustave Courbet's 1866 painting, show us "The Origin of the World," the place where we came from and the place that gave birth to our modernity based on the hubristic consumption of sugar, among other superfluous goods. The caricatured portrayal of both her protruding lips and vulva veer to an abstraction that makes them resemble geometric circles more than personalized human traits.30On the process of the "white gaze" smoothing out the body of "black subjects," by dismissing any individual characteristics, see Frantz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2008). The round and smooth vulva resembles the fleshy lips as turned from horizontal to vertical, as if the mouth could be violated like the vulva, or, in a more optimistic reading, as if labia could also speak, tell their story of exploitation.31On a related discussion of the correspondence between lips and labia, both called "lèvres" in French, see Lynn Huffer's Are the Lips a Grave? A Queer Feminist on the Ethics of Sex (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013). As Walker crucially explains in her interview with Audie Cornish, "She's positioned with her arms flat out across the ground and large breasts that are staring at you." While her eyes are closed or perhaps even carved out, her gaze appears in unexpected places that are, in a slavery context, sites of enslavement, theft, and resistance.

|

| Click to load interactive 3-D model of the Sugar Baby sphinx, from Creative Time. © 2014 Creative Time. Photograph of sphinx, Brooklyn, New York, June 13, 2014. Photograph by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. |

"The Marvelous Sugar Baby" cannot be confused with Nina Simone's "Sweet Thing," available for the taking. Despite the apparent offering, her strength prevails. The decidedness of her chin and lips facing forward in a dignified pout offers a strong resistance to the gaze that fails to penetrate the enigmatic face. The powerful curves of her back and backside look like impassible mountains. The scale of the body makes it impossible to seize. To estimate the whole we miniature figurines have to walk around the enormous statue. We are turned into tiny black cut-out shadows next to her enormous whiteness. We are turned into Kara Walker's silhouetted figures, included in the creation of her world, and also part of that history.32Africana Studies scholar Noliwe M. Rooks deplores the fact that reviews of Walker's "A Subtlety" have been overwhelmingly positive and that critics and journalists have ignored the reception of the piece by black women (Noliwe Rooks, "Black Women's Status Update," The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 26, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://chronicle.com/article/Black-Womens-Status-Update/147351/). She also points out that some of the white visitors behaved in ways that were "not just ignoble but also disrespectful" by, for instance, posing in explicitly sexual postures with the statue. Rooks's point is especially well taken not only for its crucial political dimension, but also in that, as I argue, the visitors become not only part of the show, but also incorporated into it. The ignoble gestures to which Rooks alludes become part of this repeated, unfinished, unending history of oppression.

From our Lilliputian perspective, we visitors, cannot stare her straight in the eye but have to look up towards her, as if staring at an imposing god. She is, after all, a Sphinx with enormous lion shoulders, hind legs, and forelegs ending in human hands and feet solidly anchored into the ground. The main visual inspiration for the piece seems to be the famous Great Sphinx of Giza,33For an extensive review of Kara Walker's iconographic influences, see "Kara Walker: Process and Inspiration," Creative Time, accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/inspiration/. known as the "Terrifying One" and "Father of Dread" and "believed to represent the face of the Pharaoh Khafra."34"Great Sphinx of Giza," accessed June 30, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza. The sphinx is also, according to ancient Greek mythology, the one who is in control of the riddle and thereby the power of knowledge. The sphinx is a cannibal who devours the travelers who cannot answer her riddles.35"Sphinx," in Theoi Greek Mythology: Exploring Greek Mythology in Classical Literature and Art, ed. Aaron J. Atsma, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.theoi.com/Ther/Sphinx.html. This last attribute is particularly resonant in the world of slavery and postslavery in which sugar cane plantation cultivation and sugar factories are perceived as cannibalistic machines.36 Among many examples of the factory as a cannibalistic machine eating up the cane workers and vomiting them out, see Aimé Césaire's Notebook of a Return to the Native Land: (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 4: "[the] mills, slowly vomiting out their human fatigue." In its etymology, the sphinx is "the one who strangles."37"From Greek Sphinx, said to mean literally 'the strangler,' a back-formation from sphingein 'to squeeze, bind.'" See "sphinx (n.)," in Online Etymology Dictionary, ed. Douglas Harper, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=sphinx. The contracting sphincter muscles of the esophagi, anus, or vagina derive from the same etymon. No vulnerable object, the sphinx is the one that strangles. The added components to sphinx mythology in Walker's statue are its hyper-feminization and racialization, which inscribe her in a precise historical reality, as well as in a history of oppression by caricature. The devouring sphinx-mammy is a combination of two of the most powerful stereotypes used to define Caribbean and African American women.38On the prevalence of the figure of the cannibal as a controlling image, see Loichot, The Tropics Bite Back, especially xix–xxiii. However, since she is carved out of sugar, it is not a woman, but the materiality created by slavery that is the cannibal.

|

| The Sugar Baby sphinx inside Kara Walker's A Subtlety, Brooklyn, June 13, New York, 2014. Photograph by Valérie Loichot. Courtesy of Valérie Loichot. |

I leave the exhibit with a riddle: why did Domino Foods donate eighty tons of sugar for the confection of Walker's work?39 For a full list of sponsors, including Domino Foods, see "Kara Walker: Project Support," Creative Time, accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/project-support/. Why did a company that continues to be the largest producer and marketer of refined sugar in the United States chose to fund an exhibit that is so critical of its very existence? How could Kara Walker accept the gift without compromising the mission of her installation and tainting her own work? Is the donation a gesture of largesse from the "master"? Is it a marketing strategy to increase the visibility of the company? Is the sugar gift tainted with blood, or is it an honest, albeit insufficient, act of reparation? Walker's Subtlety provides neither satiety nor answer. Instead, it leaves us with a relentless urge to question topped by an indigestion. While Walker is clearly critical of Domino Foods, and, by extension, of slavery, economic, sexual, and pictorial exploitation of human bodies, mass production and mad consumption, it is not clear as to whether art can satisfactorily fight these forces. I doubt the installation will discourage me from eating sugar. Nonetheless, it is precisely in its aggressive conundrum, in its power to cause anger, outrage, rage, awe, guilt, shame, laughter, wonder, understanding, or action that Walker's interactive and transient installation succeeds in keeping us engaged.

About the Author

Valérie Loichot is a professor of French and English at Emory University. She is the author of Orphan Narratives: The Postplantation Literatures of Faulkner, Glissant, Morrison, and Saint-John Perse (University of Virginia Press, 2007) and The Tropics Bite Back: Culinary Coups in Caribbean Literature (University of Minnesota Press, 2013). Her current projects include "Caribbean Creolization in the United States: Translating Race from Lafcadio Hearn to Barack Obama" and the forthcoming monograph Water Graves.

Recommended Resources

Text

Aronson, Marc and Marina Budhos. Sugar Changed the World: A Story of Magic, Spice, Slavery, Freedom, and Science. Boston: Clarion Books, 2010.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Loichot, Valérie. The Tropics Bite Back: Culinary Coups in Carribbean Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Audio/Video

Cornish, Audie. "Artist Kara Walker Draws Us Into Bitter History With Something Sweet." National Public Radio, May 16, 2014. http://www.npr.org/2014/05/16/313017716/artist-kara-walker-draws-us-into-bitter-history-with-something-sweet.

Walker, Kara and Jad Abumrad. Interview, Live from the New York Public Library, May 20, 2014. http://www.nypl.org/events/programs/2014/05/20/kara-walker-0.

Web

Creative Time. "Kara Walker's A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby." http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Robert Southey, The Poetical Works of Robert Southey (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1839), 110. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Kara Walker, A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, May 10–July 6, 2014, Brooklyn, New York: Domino Sugar Factory. |

| 3. | "Il n'arrive point de barrique de sucre en Europe qui ne soit teinte de sang humain." Claude-Adrien Helvétius, Œuvres Complètes, Vol. 1 (Paris: Lepetit, Editeur, 1777), 25. Author's translation. |

| 4. | Jody Dunville, "Blood Sugar," accessed June 30, 2014, http://web.utk.edu/~gerard/romanticpolitics/bloodsugar.html. On the "blood sugar" topos in Coleridge's 1795 lecture on the slave-trade and Southey's 1797 sonnets, see Timothy Morton, "Blood Sugar," in Romanticism and Colonialism: Writing and Empire 1730–1830, ed. Tim Fulford and Peter J. Kitson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 87–106. Also consult anthropologist Sidney Mintz's seminal Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin, 1985). |

| 5. | Audie Cornish, "Artist Kara Walker Draws Us Into Bitter History With Something Sweet," National Public Radio, May 16, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.npr.org/2014/05/16/313017716/artist-kara-walker-draws-us-into-bitter-history-with-something-sweet. |

| 6. | In sugar cane producing French Overseas Departments—Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Reunion—the incidence of diabetes is twice as high as in continental France. "Le Diabète Explose en France: 2 Fois Plus de Diabétiques dans les Dom-Tom Qu'en Métropole," Docbuzz: L'Autre Information Santé, November 13, 2010, accessed July 2, 2014, http://www.docbuzz.fr/2010/11/13/123-le-diabete-explose-en-france-2-fois-plus-de-diabetiques-dans-les-dom-tom-qu%E2%80%99en-metropole. For the diabetes epidemics in the Caribbean, also see Ludmilla F. Wikkeling-Scott, "Addressing Diabetes, A Regional Epidemic in Caribbean Populations," June 5, 2012. Type 2 diabetes also has such prevalence in the US South that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention coined the term "Diabetes Belt": Melissa Healy, "Diabetes Belt: American South Gets More Health Notoriety," Los Angeles Times, March 8, 2011, accessed June 30, 2014, http://articles.latimes.com/2011/mar/08/news/lat-diabetes-belt-20110308. |

| 7. | The Domino Sugar Factory will be demolished in August 2014. The operating New York area Domino factory is located in Yonkers. Before the demolition, the "Marvelous Sugar Baby" will be melted down. Some of the resin figurines will be salvaged for museum exhibits. For the recollections of Robert Shelton, who worked on the floor of the Domino factory for twenty years see Vivian Yee, "2 Jobs at Sugar Factory, and a Lump in the Throat," New York Times, July 5, 2014, accessed July 5, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/05/nyregion/recalling-sticky-hot-job-before-old-domino-sugar-factory-falls.html. |

| 8. | Writing on the wall of the exhibit entrance at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, New York. |

| 9. | On the sanitary and safety state of the building at the time of the exhibit, see Claire Voon's "How are they Keeping Rats Off Kara Walker's Sugar Sculptures?," Hyperallergic: Sensitive to Art & Its Discontents, June 10, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://hyperallergic.com/130365/how-are-they-keeping-rats-off-kara-walkers-sugar-sculptures. |

| 10. | I am grateful to my friend and colleague, Professor Naïma Hachad, who helped me brainstorm during and after the exhibit and enriched this piece with her insights. |

| 11. | Jerry Saltz, "Kara Walker Bursts Into Three Dimensions, and Flattens Me," Vulture, May 31, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.vulture.com/2014/05/art-review-kara-walker-a-subtlety.html. |

| 12. | "Creative Time presents Kara Walker's A Subtlety," accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/. |

| 13. | "Confectionery," Wikipedia, accessed June 30, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confectionery. |

| 14. | Nato Thompson, "Curatorial Statement," accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/curatorial-statement/. |

| 15. | "Walker went down a rabbit hole of sugar history, at one point stumbling on some black figurines online—the type of racial tchotchkes that turn up in a sea of mammy cookie jars," Audie Cornish, "Artist Kara Walker Draws Us Into Bitter History With Something Sweet," National Public Radio, May 16, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.npr.org/2014/05/16/313017716/artist-kara-walker-draws-us-into-bitter-history-with-something-sweet. |

| 16. | Valérie Loichot,The Tropics Bite Back: Culinary Coups in Caribbean Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013). See also Mimi Sheller's Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (London: Routledge, 2003) and Jack D. Forbes's Columbus and Other Cannibals (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008). |

| 17. | See, for instance, Devery Anderson, Emmetttillmurder.com, accessed June 30, 2014. |

| 18. | See Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw's Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004). |

| 19. | Walker's installation resembles in its evolution Jason deCaires Taylor's underwater sculptures (accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.underwatersculpture.com/sculptures). However, while Taylor's sculptures' evolution with their coral environment conveys rejuvenation, Walker's art's alliance with the industrial site evokes degeneration. |

| 20. | For Hortense Spillers, the reduction to bare flesh is the condition of enslaved Africans. The critic reads the marking of the flesh of the New World African woman, of the "seared, divided, ripped-[apart], riveted to the ship's hole, fallen, or 'escaped' overboard," as a cultural text whose marking and branding "transfers from one generation of the other." See Hortense Spillers, Black, White, and In Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 206–207. |

| 21. | Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 5, viii. |

| 22. | For Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, the hold of the slaveship, the slave plantation and its machinery constitute "bellies of the world," functioning at once as expelling guts and sheltering womb. See my Orphan Narratives for a discussion of Glissant's ambivalent bellies of the world: Valérie Loichot, Orphan Narratives: The Postplantation Literature of Faulkner, Glissant, Morrison, and Saint-John Perse (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007). For Cuban writer Antonio Benítez Rojo as well, the sites of slavery and exploitation are also the wombs of modernity without which the industrialized world would not have been born. The Brooklyn Domino Sugar Refinery, established in its Williamsburg, New York, location in 1882, was the largest sugar refinery in the world, hence, a major belly of the world. Thompson explains that "The Domino Sugar refinery is certainly an integral part of the story of sugar. Built by the Havemeyer family in 1856, by 1870 it was refining more than half of the sugar in the United States, producing over 1,200 tons of the sweet stuff every day." See Thompson, "Curatorial Statement." |

| 23. | William Faulkner, Light in August (New York: Vintage International, 1990), 465. |

| 24. | "Thy lips, O my bride, drop honey." Source: "Song of Songs, Chapter 4," The Complete Hebrew Bible, accessed June 30, 2014http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt3004.htm. |

| 25. | "Billie Holiday—Sugar," YouTube, accessed June 30, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_UajeQsQrRA&feature=kp. |

| 26. | "Nina Simone—Four Women," YouTube, accessed June 30, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WRmzQ39sXTQ. |

| 27. | "And they took my milk!" See Toni Morrison, Beloved (Knopf: New York, 1994), 19. In her Washington Post piece (McDonald, "Going to See Kara Walker's A Subtlety? Read These First," Washington Post, May 27, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/05/27/going-to-see-kara-walkers-subtlety-read-these-first/), Soraya Nadia McDonald gives a non-inclusive reading list of novels by Morrison, Maryse Condé, Jean Rhys, and Jamaica Kincaid, who have focused on similar issues. |

| 28. | On "American Primitives," see Grace Elizabeth Hale's "A Horrible, Beautiful Beast," Southern Spaces, March 6, 2008, accessed June 30, 2014, https://southernspaces.org/2008/horrible-beautiful-beast. On the politics and aesthetics of milk in Kara Walker, see Patricia Yaeger's "Circum-Atlantic Superabundance: Milk as World-Making in Alice Randall and Kara Walker," American Literature 78, no. 4 (2006): 769–798. |

| 29. | For another contemporary take on the trope, see Beyoncé Knowles's 2006 "Suga Mama" in which the star sings on what looks like a white sugar cube in a pose reminiscent of the Marvelous Sugar Baby's four-legged pose. Beyoncé as well takes an ironic twist on the image, bending gender roles as she begins the song dressed as a stereotypical providing "suga daddy" rather than a "suga mama": "And I've always been the type to take care of mine / I know just what I'm doing . . . Puttin' you on my taxes already, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah." See "Beyonce—Suga Mama," Vagalume, accessed July 27, 2017, https://www.vagalume.com.br/beyonce/suga-mama.html. |

| 30. | On the process of the "white gaze" smoothing out the body of "black subjects," by dismissing any individual characteristics, see Frantz Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2008). |

| 31. | On a related discussion of the correspondence between lips and labia, both called "lèvres" in French, see Lynn Huffer's Are the Lips a Grave? A Queer Feminist on the Ethics of Sex (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013). |

| 32. | Africana Studies scholar Noliwe M. Rooks deplores the fact that reviews of Walker's "A Subtlety" have been overwhelmingly positive and that critics and journalists have ignored the reception of the piece by black women (Noliwe Rooks, "Black Women's Status Update," The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 26, 2014, accessed June 30, 2014, http://chronicle.com/article/Black-Womens-Status-Update/147351/). She also points out that some of the white visitors behaved in ways that were "not just ignoble but also disrespectful" by, for instance, posing in explicitly sexual postures with the statue. Rooks's point is especially well taken not only for its crucial political dimension, but also in that, as I argue, the visitors become not only part of the show, but also incorporated into it. The ignoble gestures to which Rooks alludes become part of this repeated, unfinished, unending history of oppression. |

| 33. | For an extensive review of Kara Walker's iconographic influences, see "Kara Walker: Process and Inspiration," Creative Time, accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/inspiration/. |

| 34. | "Great Sphinx of Giza," accessed June 30, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Sphinx_of_Giza. |

| 35. | "Sphinx," in Theoi Greek Mythology: Exploring Greek Mythology in Classical Literature and Art, ed. Aaron J. Atsma, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.theoi.com/Ther/Sphinx.html. |

| 36. | Among many examples of the factory as a cannibalistic machine eating up the cane workers and vomiting them out, see Aimé Césaire's Notebook of a Return to the Native Land: (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 4: "[the] mills, slowly vomiting out their human fatigue." |

| 37. | "From Greek Sphinx, said to mean literally 'the strangler,' a back-formation from sphingein 'to squeeze, bind.'" See "sphinx (n.)," in Online Etymology Dictionary, ed. Douglas Harper, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=sphinx. |

| 38. | On the prevalence of the figure of the cannibal as a controlling image, see Loichot, The Tropics Bite Back, especially xix–xxiii. |

| 39. | For a full list of sponsors, including Domino Foods, see "Kara Walker: Project Support," Creative Time, accessed June 30, 2014, http://creativetime.org/projects/karawalker/project-support/. |