Overview

Claudio Saunt reviews Katherine M. B. Osburn's Choctaw Resurgence in Mississippi: Race, Class, and Nation Building in the Jim Crow South, 1830–1977 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

Review

|

In this meticulously researched book, Katherine M. B. Osburn follows the history of the Mississippi Choctaws from the Antebellum era to the "Choctaw Miracle" of the 1970s, when this small community emerged from poverty and built thriving businesses in plastics and direct-marketing. Osburn is especially interested in how the Choctaws navigated their way through Mississippi's racial currents, as powerful and relentless as the muddy river itself.

Divided into eight chapters, Choctaw Resurgence offers a careful reconstruction of Choctaw agency. Osburn writes often about Choctaw strategies that were employed or deployed in the interest of preserving and furthering self-determination. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, she explains, the Choctaws "laid the foundations of the political rhetoric and strategies that they would employ" for the next century (9). They marketed crafts to "bolster their ethnicity" (22), pursued a "strategy" of separatism from black Mississippians in the face of Klan violence (28), and "marked their ethnicity" every Sunday by wearing traditional clothing (29). Even education became a tool to reinforce their identity (33, 58). Other Indians in the South pursued similar strategies, but arguably no people have had quite as much success as the Mississippi Choctaws.1Works that describe the struggles of other native peoples in the post-Civil War South include Brian Klopotek, Recognition Odysseys: Indigeneity, Race, and Federal Tribal Recognition Policy in Three Louisiana Indian Communities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Malinda Maynor Lowery, Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, and the Making of a Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); and Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Osburn's overarching narrative, if not the specifics of the struggle, is fascinating. As a result of their hundred-year battle, this formerly isolated and impoverished group, reduced to some five hundred individuals by the 1920s (88), was able to maintain its indigenous identity, make successful demands on the federal government, and become one of the economic powerhouses in modern-day Mississippi. Along the way, they faced the nearly impossible challenges of pleasing segregationist whites, asserting their own distinctiveness, and keeping black Mississippians at a distance.

|

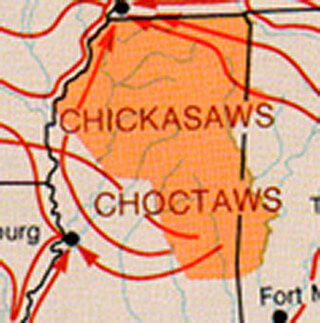

| The 1827 Anthony Finley Map of Mississippi depicts the extent of the Choctaw nation in the state. It is featured on the cover of Osburn's book. Photograph by Geographicus Rare Antique Maps. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

|

| An outdoor portrait of Jim Tubby, Neshoba County and Scott County, Mississippi, 1908. Photograph by Mark Raymond Harrington. Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Mississippi Choctaw Collection, P12169. |

Choctaw history is packed with ironies and reads sometimes like an "only in America" tale. After the Civil War, for example, Mississippi's most ardent white supremacists embraced the Choctaws. In their view, both groups were southerners with a mystical connection to the land; both had fought for a glorious cause against the despotic federal government; and both were noble in defeat. Moreover, white politicians realized that by supporting Choctaw sovereignty there was federal pork to be had. As a result, when Senator James Vardaman wasn't railing against the "lazy, lying, lustful animal" that he more politely called "the Negro," this arch white supremacist lobbied to help the Choctaws secure federal assistance (48). Unlike Mississippi's black citizens, asserted Vardaman's fellow senator John Sharp Williams, Choctaws lived "an honest and simple life" (51). Later, Theodore Bilbo would also take up the Choctaw cause in Washington.

The lobbying bore fruit. In 1928, the federal government subsidized the construction of the only hospital in all of Nashoba County. Located in Philadelphia, Mississippi, the hospital was reserved exclusively for Indians. States' rights advocates could not resist the spoils and soon called for an Indian boarding school, hoping that the improvements to infrastructure would benefit the county's whites as well (79). Meanwhile, the Choctaws found themselves embracing segregation and scientific racism in order to protect their distinct position in Jim Crow Mississippi. They were "full bloods," they insisted over and over again, and should not be lumped together with the state's black residents.

By the 1930s, the Choctaws were teaming up with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to send a Choctaw woman to North Carolina to learn to make native dyes. "Authenticity" in handicrafts, Choctaws and BIA agents understood, would create a more marketable product (105). As the Choctaws improved their standing with the BIA, tension increased between their desire for self-determination and their desire for federal aid, two goals that turned out not to be mutually exclusive. "Using the resources of the Great Society," Osburn concludes, Choctaws "finally resolved the myriad dilemmas created by BIA paternalism" (150). That is, they were able to leverage one federal agency against another and extract themselves from the heavy hand of BIA officials. By wisely investing federal funds, they launched the "Choctaw Miracle."

Today, the Mississippi Choctaws are among the most successful of Indian nations, and their prosperity rests not solely on Indian gaming, but on a broad portfolio of enterprises. This nation of 10,000 people employs nearly 6,000 individuals full time, making it one of the ten largest employers in Mississippi. They operate hi-tech firms specializing in robotics, calibration, and metrology, run an office supply company, and own a business park that is home to firms producing equipment for unmanned aircraft and military vehicles. Irony abounds: Because of the various sovereign rights that Great Society Democrats and others recognized in Indian country, Choctaws were able to create a pro-business environment, even marketing the reservation as a shelter from lawsuits (204).

| |

| Group of Choctaw men, a young woman and a young girl posed outdoors, probably at a stick ball game, Neshoba County and Scott County, Mississippi, 1908. Photograph by Mark Raymond Harrington. Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Mississippi Choctaw Collection, N02667. | |

| |

| Choctaw Nation Labor Day Stickball Tournament. Photograph of Beaver Dam Team. Posted to Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians Public Facebook Page, September 2, 2014. |

Osburn skillfully highlights various strategies Choctaws used to chart their way through Mississippi's racial politics, but at times, she perhaps pushes her analysis too far. There is so much employing and deploying of strategies to further national interests that the Choctaws begin to resemble an improbably successful team of policy analysts and political scientists. "Indians deployed race," she summarizes in the epilogue (210). Racism is insidious, however, and it seems unlikely that any population in North America—and most especially in the US South—can live outside it or wield it as a strategic tool, to be taken up when useful, laid aside when not.

Nonetheless, Osburn's approach underscores how the Mississippi Choctaws had an active hand in determining their future. Carefully researched and clearly written, Choctaw Resurgence in Mississippi is a welcome and much-needed investigation into the unlikely survival and surprising success of this remarkable indigenous community.

About the Author

Claudio Saunt is the Richard B. Russell professor in American History, Associate Director of the Institute of Native American Studies, and the Co-Director of the Center for Virtual History at the University of Georgia. His works include West of the Revolution: An Uncommon History of 1776 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014) and Black, White, and Indian: Race and the Unmaking of an American Family (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Recommended Resources

Text

Carson, James Taylor. Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

Lambert, Valerie. Choctaw Nation: A Story of American Indian Resurgence. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Web

Gardner, Chief David. "A Brief Talk on Choctaw History," Hello Choctaw, December 1, 1976. http://www.choctawnation.com/history/choctaw-nation-history/removal/a-brief-talk-on-choctaw-history.

Choctaw Indian Fair. 2014. http://www.choctawindianfair.com.

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. 2013. http://www.choctaw.org

Similar Publications

| 1. | Works that describe the struggles of other native peoples in the post-Civil War South include Brian Klopotek, Recognition Odysseys: Indigeneity, Race, and Federal Tribal Recognition Policy in Three Louisiana Indian Communities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Malinda Maynor Lowery, Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, and the Making of a Nation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); and Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996). |

|---|