Overview

Alexis S. Wells reviews Ras Michael Brown's African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Review

|

Although scholars of the African diaspora have long acknowledged the persistence of African cultural forms within the musical, material, and linguistic cultures of African Americans in the United States, with few exceptions, the prevailing wisdom concerning religion has been: "In the United States the gods of Africa died."1On the non-survival of African forms, see Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South, updated edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004 [1978]), 86. Brown references Raboteau's statement in the first sentence of his Prologue, which speaks to the significance of Raboteau's text in setting the methodological agenda for many subsequent studies. For more on the influence of Raboteau's study on studies of US African American religious cultures, see Dianne M. Stewart Diakité and Tracey E. Hucks, "Africana Religious Studies: Toward a Transdisciplinary Agenda in an Emerging Field," Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 1 (January 2013): 37. One of the most significant reports on African forms in Lowcountry religious cultures is the Georgia Writers' Project, Savannah Unit, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, (Spartanburg, SC, Reprint Co, 1974 [1940]). Consequently, US African American religious cultures have rarely figured as prominently as their Caribbean and South American counterparts in conversations about African cultural continuities in the African-Atlantic—the geographical, cultural, and symbolic space linked by the dispersion of African-descended peoples across the Atlantic.2Although a number of studies reference African antecedents in their analysis of African American religions, few attempt to trace the persistence of African spirits in the United States. Published in the field of art history, one notable exception is Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, (New York: Vintage Books, 1983). With his 2012 publication, African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry, University of Illinois-Carbondale history professor Ras Michael Brown joins a small group of scholars who are re-engaging the United States, particularly the Anglophone American South, in conversations about African-Atlantic religions. He situates the South Carolina Lowcountry as a "Bantu-Atlantic spiritual landscape rooted in West-Central Africa," where Kongo nature spirits, called simbi, manifested in the rituals, mythology, folklore, and worldsense of enslaved Africans and their descendants from the arrival of Africans in 1670 to the flooding of simbi territory in the early 1940s.3Ras Michael Brown, African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 5. On the significance of the term "worldsense" to studies of African cultures, see Oyeronke Oyewumi, The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 3. In the Lowcountry, the gods of Africa did not die—but in fact—enjoyed a reign far beyond the estimations of previous studies of the region.

By putting the South Carolina Lowcountry in dialogue with West-Central Africa and the Western hemispheric African Atlantic, Brown revives the iconic debate between anthropologist Melville Herskovits, who privileged African antecedents in the analysis of African American forms, and sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, who privileged US African American innovation.4Melville J. Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990 [1941]). E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939). Brown understands continuity and creativity as interdependent products of African American agency. Africans and their descendants in the Lowcountry did not "retain" practices—an idea which neglects the role of agency in the maintenance and adaptation of sacred cultures—but elaborated upon the principles and practices of their African ancestors over the course of three centuries, even amid the ruptures imposed by enslavement and Protestant Christianity. They remained in dialogue with their homelands through the conscious transmission of spiritual ideas and practices regarding the visible elements of the natural world. For displaced Africans, the Lowcountry was not solely a place of captivity, but also an "African conceptual space that connected the visible, physical domain with the invisible, spiritual realm."5Brown, 143. Employing sources that span from sixteenth-century European traveler accounts of Kongo practices to the early twentieth-century oral histories of Lowcountry African American Protestants, Brown's study traces the simbi, and similar nature spirits, across time and diaspora to argue for a dynamic understanding of West Central African sacred forms in the US.

Although Brown is not the first to use West or West-Central African spirituality as an interpretive framework for Lowcountry African American religious formations,6See Margaret Washington Creel, A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs (New York: New York University Press, 1988); Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance: African Atlantic Religion in Kongo and the Lowcountry South in the Era of Slavery (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007). the scarcity of data on the simbi during the height of the slave trade to the Lowcountry and on African religious formations in the United States during slavery require methodological innovations from scholars who study non- and pre-Christian religions amongst African Americans. Historians frequently use the presumed cultural heterogeneity of the captive Africans to justify their decisions to elide ethnic and regional specificity in the interpretation of religious forms, and to instead begin the conversation in the Americas. Brown uses probate records, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, and plantation inventories to suggest a Kongo majority in the South Carolina Lowcountry during the formative, frontier period of the region between 1670 and 1750. As members of the Niger-Congo language family, captives from Senegambia, the Bight of Biafra, and West-Central Africa—the most well-represented regions of origin amongst Lowcountry Africans—shared similar understandings of the spiritual dimensions of the natural world. Information about the Kongo simbi, and similar nature spirits, anchor Brown's analysis of Lowcountry beliefs and practices.

|

| Map of west Africa depicting the prominent regions of origin of Lowcountry Africans, 2013. Map created by Southern Spaces. |

|

| General Map of the Carolinas with location of the Cooper River indicated, Amsterdam, 1683. Map by Nicolas Sanson. Courtesy of the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection, SouthCarolina1683a.sid. |

Brown contends that the absence of nature spirits from discussions of African-descended people in the Lowcountry results from the imposition of Judeo-Christian concepts of an omnipresent, universal God, a rigid bifurcation of the visible-natural and the invisible-spirit worlds, and the hegemony of Western definitions of religion.7Brown, 26–27, 30. In the West-Central African worldsense, the land of the living and the land of the dead exist as separate places in the unified space of the natural world; as "invisible physical forces" on the "continuum of being," the simbi inhabit the natural world, just as elements of the natural world, such as rocks and springs, compose the spiritual landscape.8Ibid., 102. Brown's reference to "'invisible physical forces'" comes from Buakasa Tulu Kia Mpansu, L'Impensé du Discours: "Kindoki" et "Nkisi" en Pays Kongo du Zaire (Kinshasa: Presses Universitaires du Zaire, 1973), 239–240, 299–300. Brown uses the West-Central African worldsense to discern the spiritual dimensions of mundane acts, such as planting, fishing, and hunting, as well as the African spiritual elements of Protestant Christianity.

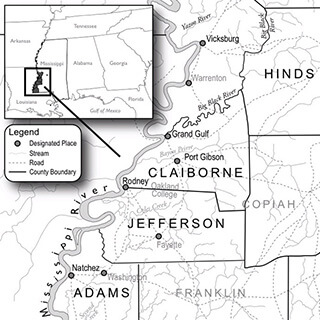

The versatility of the simbi—historically and as a methodological concept in African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry—emerges from the fluid form and function of nature spirits, which are understood as either "primordial" ancestors originating from the land of the dead or iterations of people who once inhabited the land of the living. Most importantly for Brown, the simbi constitute a class of spirits that do not require the remembrance of lineal kin to gain influence in the land of the living. As the primordial inhabitants of lands, the simbi were already present in the Lowcountry when the first African captives disembarked, and their presence established displaced Africans' connections to the Lowcountry. With this subtle but significant claim, Brown suggests the persistence of an African worldsense and locates the West-Central African simbi in the springs of the limestone region (the western tributary of the Cooper River) of South Carolina—a region possessing the quintessential topographical features of simbi territory.

Anthropologist Igor Kopytoff's concept of precedence provides the foundation for Brown's discussion of the pioneer generation of Lowcountry Africans, or "firstcomers," and their role in the entrenchment of the West-Central African worldsense, as represented by the simbi.9Igor Kopytoff, "The Internal African Frontier: The Making of African Political Culture," in The African Frontier: The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies, ed. Igor Kopytoff (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). The status of first inhabitants as "owners" of the land imbues them with the right and responsibility to narrate and shape the spiritual landscape. Citing the work of Kongo scholar Buakasa Tulu Kia Mpansu, Brown points out that some Kongo peoples underscored the ritual function of the simbi to reconcile Kongo newcomers' relationship to the land and to reestablish community in the wake of conquest.10Brown 88. Buakasa, L'Impense du Discours, 294–295. Yet the simbi's inhabitance of the space between the land of the living and the land of the dead enabled them to assume the social function of familial ancestors. In the Americas, African captives within the Bantu-Kongo spiritual lineage mitigated the crisis of estrangement from consanguineous ancestors through the collective adoption of ancestors in the form of the simbi, and "cognate spirits" called nkisi and nkita.11Brown, 30, 91, 106. The simbi, nkisi, and nkita are all "spirits of place"; they are spirits of similar function in different regions of West and West-Central Africa. The nkisi are the nature spirits of the north side of the Nzadi River, and the nkita are the similar spirits of the Eastern provinces of Kongo. Brown surmounts the relative obscurity of the simbi in Kongo historical records during the period of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade by using data on the nkisi and nkita to augment his discussion of the simbi prior to the nineteenth century.

Using traveler, merchant, and scholarly accounts of simbi, nkisi, and nkita from the sixteenth through twentieth centuries in Kongo, along with oral histories, diaries, planter papers, and anthropological accounts of the Lowcountry during and following slavery, Brown expertly demonstrates that the form and meaning of the simbi developed over time, on both sides of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Sacred stories present the varied understandings of nature spirits as powerful guardians of human livelihood, spiritual experts (banganga) transitioned to the land of the dead, initiators of migrations, primordial inhabitants of natural formations, facilitators of natural disasters, and catalysts of illness. Brown concedes that captive Africans likely did not transport beliefs about the simbi wholesale to the Americas and notes variant interpretations of the simbi among continental and Lowcountry Africans in response to the slave trade. While some continental Africans began to understand the simbi as executors of misfortune and sought to harness their powers through capture, Lowcountry Africans used the simbi to construct a sense of place amid captivity and displacement. Brown suggests that nature spirits provided a common spiritual lexicon for Africans in the earliest Lowcountry societies and persisted—even as the number of Carolina-born people increased—due to the coexistence of multiple arenas of identity and contact.12This point is an elaboration upon Michael A. Gomez's concept of polyculturalism. Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 10.

In his most innovative turn, Brown traces the history of nature spirits in the Lowcountry, against the claim that the "gods of Africa died" in the US. Linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner's work provides source material for Brown's discussion of the West-Central African worldsense evidenced in the subsistence activities of enslaved Lowcountry Africans.13Lorenzo Dow Turner, Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949). As the guardians of the landscape, the simbi sanctioned and ensured the success of subsistence activities. The persisting use of Bantu terms and consecrated objects among enslaved Africans in reference to hunting, fishing, and farming activities points towards the importation of West-Central African concepts of the spiritual landscape into US African American understandings of the natural world. Likewise, the prominence of the simbi by the early nineteenth century speaks to the significant influence of the seventeenth-century pioneers upon the re-imagining of American lands through African rubrics and, consistent with Brown's emphasis upon agency, suggests "conscious and repeated choices by African-descended people" to retain particular ways of conceptualizing plants, animals, and subsistence activities.14Brown, 145. Contrary to passive notions of African "retentions," Brown uses newspaper accounts of enslaved peoples' self-emancipation attempts to argue for the importance of the mfinda (forest) as a site of material and symbolic protection and peril. Moreover, he links stories of enslaved peoples' journeys and, at times, deaths in the mfinda to the spiritual significance of the wilderness as a space inhabited by the ancestors and as a threshold between the land of the living and the land of the dead.

As African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry progresses, the question of the interaction between the West-Central African worldsense and Christianity, particularly southern Protestantism, looms. Brown contends that the Kongo simbi provide an interpretive key through which to understand the white bundles and babies that appear in Lowcountry African Americans' Christian conversion experiences, or "seeking" rituals.15Ibid., 242, 245. Brown uses Kongo initiation societies, such as the Lemba society, to make this point. Creel, A Peculiar People, 2, 47, 285. In her exploration of the Gullah community during enslavement, Creel argues that the Poro-Sande societies of present-day Sierra Leone and Liberia were adapted to and fused with the Gullah Christian practice of "seekin" to create adult initiation rites. The prevalence of the color white, the appearance of the beings/objects as either bundles or babies, and the experience of the beings/objects within the context of spiritual transformation echo ideas around the simbi. Yet, since the nature spirits are unnamed within their Christian iterations, Brown offers accounts of Kongo people's engagement with Christianity, and their endowment of European Christian figures such as the Virgin Mary with simbi functions, to establish precedence for simbi symbolism in Lowcountry Christianity.16Brown, 209. Similarly, in his analysis of the mermaids and sirens of Lowcountry folklore, he moves beyond the European images and terminology to instead note the ways they assume the maternal and nature-controlling qualities of the simbi.

Brown challenges interpreters of religion to transcend explanations that hasten to locate US African American practices as either African or American in origin, and, instead, acknowledges the potential for cohabitation and communication between seemingly rival cosmologies. In this way, African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry responds to religion scholars Dianne M. Stewart Diakité and Tracey E. Hucks's call for an Africana Religious Studies agenda in which scholars "develop research parameters sensitive to the analytical necessity of conceptualizing the Atlantic and North America as dialogical spaces where ‘ethnic' continental African, pan-African, and neo-African religious cultures, including Christianity, have appeared and continue to be improvised."17Diakite and Hucks, "Africana Religious Studies," 51. For Diakite and Huck's assessment of Brown's book, see pages 57–59. Arrival in Western hemispheric lands did not make the Americas home in the eyes of captive Africans and their descendants. Rather, spiritual and ancestral presences were central to African-Atlantic peoples' notions of habitation and their transitions between geo- and religio-cultural spaces. Perhaps the most significant contribution Brown makes to the study of US African American religious cultures is the premise that captive Africans in the United States maintained West-Central African ways of understanding the world, and those understandings are traceable within historical records for much longer than previous scholars have assumed. African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry contextualizes US African American religious cultures in the transnational, transoceanic psychic and cultural space of the African-Atlantic, and offers the promise of future forays into yet unexplored scholarly terrains.

About the Author

At the time of writing this review Alexis S. Wells was a PhD candidate in the Graduate Division of Religion at Emory University working on her dissertation, "Re/Membering the Sacred Womb: The Sacred Cultures of Enslaved Women in Georgia, 1750–1861." She is currently assistant professor of Religious Studies, American Religious History, and African-American Religious History at Vanderbilt University.

Recommended Resources

Text

Creel, Washington. A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs. New York: New York University Press, 1988.

Diakité, Dianne M. Stewart and Tracey E. Hucks. "Africana Religious Studies: Toward a Transdisciplinary Agenda in an Emerging Field." Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 1 (January 2013): 28–77.

Gomez, Michael A. Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Herskovits, Melville J. The Myth of the Negro Past. Boston: Beacon Press, 1941.

Web

Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

http://www.slavevoyages.org.

Similar Publications

| 1. | On the non-survival of African forms, see Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South, updated edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004 [1978]), 86. Brown references Raboteau's statement in the first sentence of his Prologue, which speaks to the significance of Raboteau's text in setting the methodological agenda for many subsequent studies. For more on the influence of Raboteau's study on studies of US African American religious cultures, see Dianne M. Stewart Diakité and Tracey E. Hucks, "Africana Religious Studies: Toward a Transdisciplinary Agenda in an Emerging Field," Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 1 (January 2013): 37. One of the most significant reports on African forms in Lowcountry religious cultures is the Georgia Writers' Project, Savannah Unit, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Among the Georgia Coastal Negroes, (Spartanburg, SC, Reprint Co, 1974 [1940]). |

|---|---|

| 2. | Although a number of studies reference African antecedents in their analysis of African American religions, few attempt to trace the persistence of African spirits in the United States. Published in the field of art history, one notable exception is Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy, (New York: Vintage Books, 1983). |

| 3. | Ras Michael Brown, African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 5. On the significance of the term "worldsense" to studies of African cultures, see Oyeronke Oyewumi, The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 3. |

| 4. | Melville J. Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (Boston: Beacon Press, 1990 [1941]). E. Franklin Frazier, The Negro Family in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1939). |

| 5. | Brown, 143. |

| 6. | See Margaret Washington Creel, A Peculiar People: Slave Religion and Community Culture Among the Gullahs (New York: New York University Press, 1988); Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance: African Atlantic Religion in Kongo and the Lowcountry South in the Era of Slavery (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007). |

| 7. | Brown, 26–27, 30. |

| 8. | Ibid., 102. Brown's reference to "'invisible physical forces'" comes from Buakasa Tulu Kia Mpansu, L'Impensé du Discours: "Kindoki" et "Nkisi" en Pays Kongo du Zaire (Kinshasa: Presses Universitaires du Zaire, 1973), 239–240, 299–300. |

| 9. | Igor Kopytoff, "The Internal African Frontier: The Making of African Political Culture," in The African Frontier: The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies, ed. Igor Kopytoff (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). |

| 10. | Brown 88. Buakasa, L'Impense du Discours, 294–295. |

| 11. | Brown, 30, 91, 106. The simbi, nkisi, and nkita are all "spirits of place"; they are spirits of similar function in different regions of West and West-Central Africa. The nkisi are the nature spirits of the north side of the Nzadi River, and the nkita are the similar spirits of the Eastern provinces of Kongo. Brown surmounts the relative obscurity of the simbi in Kongo historical records during the period of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade by using data on the nkisi and nkita to augment his discussion of the simbi prior to the nineteenth century. |

| 12. | This point is an elaboration upon Michael A. Gomez's concept of polyculturalism. Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 10. |

| 13. | Lorenzo Dow Turner, Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949). |

| 14. | Brown, 145. |

| 15. | Ibid., 242, 245. Brown uses Kongo initiation societies, such as the Lemba society, to make this point. Creel, A Peculiar People, 2, 47, 285. In her exploration of the Gullah community during enslavement, Creel argues that the Poro-Sande societies of present-day Sierra Leone and Liberia were adapted to and fused with the Gullah Christian practice of "seekin" to create adult initiation rites. |

| 16. | Brown, 209. |

| 17. | Diakite and Hucks, "Africana Religious Studies," 51. For Diakite and Huck's assessment of Brown's book, see pages 57–59. |