Overview

Amy Louise Wood reviews Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Mob Violence Outside the South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013) edited by Michael J. Pfeifer and Swift to Wrath: Lynching in Global Historical Perspective (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013) edited by William D. Carrigan and Christopher Waldrep.

Review

"Lynching of Negroes is growing to be a southern pastime," declared the Reverend D. A. Graham of the A.M.E. church in a sermon preached in Indianapolis, Indiana, as part of a nationwide protest against the practice, organized by the National Afro-American Council in 1899.1Rev. D. A. Graham, "Some Facts About Southern Lynching," Indianapolis Recorder, June 10, 1899, reprinted on BlackPast.Org: An Online Reference Guide to African American History, accessed October 9, 2013, http://www.blackpast.org/1899-reverend-d-graham-some-facts-about-southern-lynchings. In the late nineteenth century and through the twentieth century, Rev. Graham's perception of lynching as a southern problem was a common one. After all, the overwhelming majority of the over five thousand lynchings in this period happened in the states of the former Confederacy, where terror served to enforce legalized segregation and disenfranchisement and lynching stood as the most visible and brutal signifier of Jim Crow apartheid. For these reasons, when historians began writing the history of this violence in the 1970s and 1980s, they focused their attention on its causes and effects in the South.

|

More recently, historians have come to reconsider this sectional focus, as it gives the impression that lynching was a uniquely southern practice. In fact, lynchings happened in almost every state in the nation. (Graham's quote notwithstanding, many observers at the time recognized this; civil rights activist Ida B. Wells, for instance, called lynching not a southern, but a national pastime).2Ida B. Wells, "Lynch Law in America," January 1900, accessed October 9, 2013, http://www.blackpast.org/1900-ida-b-wells-lynch-law-america. Some scholars, myself included, have studied lynching as part of a wider national consciousness through its representation in popular culture or the work of nationally-situated writers and activists. Others, as exemplified in Lynching Beyond Dixie, have researched lynching outside the South. Historians of the West have long studied vigilantism, but new scholarship on lynching draws connections between the "rough justice" of the West and other areas and southern lynchings in the Jim Crow era in part to challenge the notion that southern lynchings were categorically distinct from other vigilante practices. An emphasis on this widespread practice beyond the US South was critical to Michael Pfeifer's previous two books on lynching, and remains central in this new edited volume.

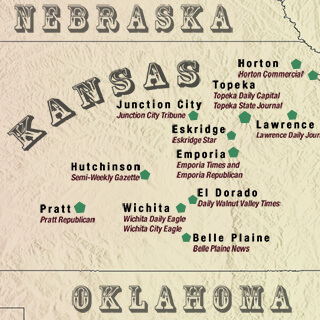

This comparative approach that examines lynching across sectional boundaries is a welcome addition. The ten essays that comprise Lynching Beyond Dixie examine lynching practices, as well as acts of resistance in the West, the Midwest, and the Northeast. This approach makes a worthy contribution to a broader historiography that seeks to undermine "the myth of southern exceptionalism," or the notion that the history of the South stands separate from that of the rest of the nation, its values disconnected from American ideals.3See, for example, Matthew D. Lassiter and Joseph Crespino, eds., The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). It is through this myth that non-southerners have projected national sins, particularly racial sins, upon the South. As Brent Campney notes in his essay on Reconstruction-era violence in Kansas, if non-southerners "inflicted less violence" in the aggregate than southerners, "they did not do so because their racism was "less deep" but because conditions differed so greatly between the sections" (101).

Lynching Beyond Dixie also has the laudable effect of bringing otherwise forgotten lives back into the historical narrative. True, the vast majority of lynching victims were southerners, but, as Sundiata Keita Cha-Jua notes in his addition to the collection, while only three percent of African Americans were lynched outside the South, "that three percent mattered" (169); as did the lives of the hundreds of Mexicans, Native Americans, Chinese, and whites who were lynched across the country. In his essay on race riots in Springfield, Ohio, Jack S. Blocker points out that from the perspective of African Americans, life was no less dangerous outside the South, since violence tended to occur in proportion to population size.

Yet, if the goal of Lynching Beyond Dixie is to challenge the distinctiveness of southern lynchings or, as Pfeifer writes, to "compel us to rethink the geography, chronology, and social relations" of lynching practices (7), it does not quite succeed. The best essays examine lynchings and responses to lynchings outside the South, not to obscure geographic (or chronological) boundaries, but to demarcate and comprehend them. What we learn is how much the practice of lynching and its effects were bound by space and place, as Campney's quote makes clear. Campney's finely-crafted essay explores Reconstruction-era racial violence in Kansas to overturn presumptions that a relative degree of interracial harmony existed there after the Civil War. That illusion of harmony was due to the influence of the state's Radical Republicans, who called for black social and legal equality out of principle or, in the case of moderates, out of a pragmatic adjustment to social reality and law. Campney, however, examines incidents of racist violence after the Civil War that reveal the attitudes of a "great mass of silenced white Kansans" (83)—a silent majority. He, importantly, shifts our conception of Reconstruction away from a series of bloody events confined to the South. Yet, his essay also shows the political forces that made those Kansans "silenced" compared to their counterparts in the South. Similarly, William Carrigan and Clive Webb's essay on the lynching of Mexicans in Arizona explores the reasons why lynching in that state ended after a 1915 lynching of two Mexican outlaws. That particular lynching spurred a strong reaction from political authorities concerned about the credibility of their new state with the rest of the nation and with business investors. Both essays underscore how drastically conditions in these two states differed from those in the South.

Two essays provide interesting case studies of local African American activism against lynching, a vastly understudied topic. Cha-Jua's offers an illuminating account of local black resistance to an 1893 lynching in Decatur, Illinois. Dennis Downey examines local responses to a 1903 lynching in Wilmington, Delaware, of a black laborer, George White, accused of assaulting a young white woman. Specifically, the lynching spurred African Americans in the city to stage a public protest led by the minister and activist Montrose W. Thornton. These essays bring to light stories of black empowerment and allow the reader to glimpse ways in which acts of protest influenced national civil rights activities. Yet, again, these essays ultimately reinforce sectional differences. Scholars of southern lynchings have found a dearth of successful public black protests in the South, not because they have not looked for them, but because the repercussions for African Americans who acted openly against lynching in the South were swift and brutal. The essays beg us to consider the conditions in northern localities that allowed protests to occur. Racial animosity might have been as deep outside the South, and certainly many citizens had equal desires for "rough justice," but countervailing forces existed in many of these non-southern states to mitigate the effects of that animosity and propensity for vengeance. Pfeifer shows as much in his essay on lynching in Michigan, where only seven people were lynched in the history of the state, due to both the "preponderance of Yankee settlers" who were more likely to reject vigilantism and accept racial equality, and the relative paucity of immigrants from the South. Ultimately, Lynching Beyond Dixie, including Pfeifer's own essay, reinforces the very geographical distinctions it was meant to challenge.

Considering this implicit conclusion, the accusatory tone in Pfeifer's introduction and in some of the essays is puzzling. In making the case for the significance of his approach, Pfeifer dismisses the value of other approaches to the topic—an unfortunate, but all too common, academic habit. In particular, Pfeifer discredits any study that takes neither a national or a comparative view as lacking and reproaches those scholars who have focused on southern lynchings for their "parochialism" (2), as if there were not legitimate reasons to study southern lynchings, many of which become apparent in reading the volume. Even more unfortunate is Cha-Jua's claim that those who have not addressed the topic of his essay—local black collective resistance to racial violence—are guilty of racism and "academic lynching" (166). Scholars of national anti-lynching efforts or other, less visible, forms of black resistance are no less guilty of this crime, in his view. This sort of scholarly one-upmanship should have been edited out.

|

The second book under review here, Swift to Wrath, pairs well with Lynching Beyond Dixie, as it expands the study of lynching even farther, taking it not just out of the South, but beyond US borders. (The collection is the second in the last two years to take a global perspective, a recent trend in the field.)4Manfred Berg and Simon Wendt, eds. Globalizing Lynching History: Vigilantism and Extralegal Punishment from an International Perspective (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011). Rather than challenge the exceptionalism of southern lynching, the editors of this collection, William Carrigan and Christopher Waldrep, two esteemed and prolific scholars in the field, want to "refute the popular notion" that lynching was "unique or exceptional to the United States" (1). Yet, as with Lynching Beyond Dixie, the collection undermines its own goal. The first section of the volume consists of five essays on various practices of collective violence that stretch geographically and chronologically from the ancient Near East to Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 1980s. Another essay, by Joël Michel, surveys various forms of collective violence in France and its colonies from the nineteenth century forward, offering various comparisons to US violence. Carrigan's contribution with co-author Clive Webb on the decline of mob violence against Mexicans in New Mexico, though a strong essay that presents a similar argument to that made in Lynching Beyond Dixie, seems out of place here. The editors do not claim that these essays provide comprehensive coverage of the topic, nor should they, but the selection of topics in this section feels somewhat disjointed and random.

I am also not convinced that it is conventional wisdom that mob violence is unique to the United States. That acts of vengeance, vigilantism, witch hunting, and other forms of collective, extra-legal violence have long histories in many cultures around the globe is surely well-known. Instead, scholars have posited that the term "lynching" was specific to the United States and has its own complicated history. As Waldrep has shown in previous work, in the United States, from the late eighteenth century through most of the nineteenth, lynching referred to acts of popular justice.5 Christopher Waldrep, The Many Faces of Judge Lynch: Extralegal Violence and Punishment in America (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002). From the late nineteenth century to the present, however, lynching was primarily associated with mob violence aimed at controlling racial minorities, primarily African Americans, and it lost its positive connotations. In most of the essays in the first section of Swift to Wrath, titled "The Practice of Lynching: From the Ancient Middle East to Late Twentieth-Century Northern Ireland," the authors seem to impose the term "lynching" on various acts of mob violence throughout history, but it is not clear what is gained by doing so. This is particularly perplexing since another stated goal of the collection is to consider lynching as a discursive act. Precisely because the word "lynching" has a fraught history, as the editors are careful to point out, to label "a violent act a lynching is often a political act" (7). What does it mean, then, for these historians to use the term to discuss historical acts of violence that participants and observers at the time did not call "lynching"? This approach is also confounding, since, in their introduction, the editors warn against using the term "lynching" to describe all acts of mob violence, thereby erasing historical context and making claims for "a universal human behavior that can be objectively understood outside time and space" (7). Unfortunately, this section of Swift to Wrath falls into the trap the editors hoped to avoid by presenting a series of essays on collective violence that imply trans-historical, trans-geographical behaviors. Any comparisons that these essays draw to lynching in the United States that could highlight historical particularities remain underdeveloped.

|

| An issue of Soviet magazine Bezbozhnik, depicting the lynching of an African American, 1930. Courtesy of Wikipedia. |

A more interesting question, which Michel's essay touches upon, is how the term "lynching" arrives in other societies, many of which use the word to describe certain acts of mob violence as a means to frame those acts politically. This is a question that Swift to Wrath takes up in its second section, which explores the discursive and representational uses of US lynchings in various contexts. The four essays in this section redeem the collection as a whole. Each is analytically sharp and nuanced, but together cohere to illuminate the wide ripple effects of lynching within and beyond US borders. Robert Zecker discusses the ways in which newspapers in Slovak immigrant communities in northern cities reported on mob violence against African Americans at the turn of the twentieth century. This coverage, which repeated the tropes and imagery of pro-lynching newspapers, schooled Slovaks in American racism, a process that furthered their Americanization and their self-conception as white citizens. Sarah Silkey provides a rich understanding of the ways in which lynching operated as a "flexible rhetorical construct" (161) in her essay on British responses to American lynchings. By conceiving of lynchings as barbaric acts of extra-legal violence—something that Americans do—British citizens were able to perceive of themselves as civilized, even as they used state violence to assert racial control over colonial subjects in Africa and India. Essays by Meredith Roman and Fumiko Sakashita examine Soviet and Japanese uses of US lynching in state propaganda during the 1930s and World War II. Both the Soviets and the Japanese, in condemning American lynchings, were able to deflect international attention from their own totalitarian abuses and imperial designs, positioning themselves as enlightened.

Notably, the foreign subjects in these essays make no real distinctions between geographies within the United States; once the coverage of lynching moves beyond US borders, "southern exceptionalism" recedes, and the goal of viewing lynching as a US rather than a southern phenomenon is achieved. Notably, "lynching" has been used to condemn acts of extralegal violence through its association with American racism. Swift to Wrath, a volume meant to move beyond a kind of US-centrism, ultimately places US racial violence at its center. Nevertheless, both these collections represent the most recent trends in the study of lynching, and, as such, they lay important groundwork and should spur further comparative studies, both within the United States and across the globe.

About the Author

Amy Louise Wood is an associate profesor of history at Illinois State University. She is the author of Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), which examines visual representations of lynching and the construction of white supremacy in the Jim Crow era. Lynching and Spectacle won the Lillian Smith Book Award and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award in History. Wood was co-guest editor with Susan V. Donaldson of Mississippi Quarterly's 2008 "Special Issue on Lynching and American Culture," and the editor of the volume on violence for the New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011).

Recommended Resources

Text

Berg, Manfred. Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America. New York: Ivan R. Dee Publishers, 2011.

Berg, Manfred and Simon Wendt, eds. Globalizing Lynching History: Vigilantism and Extralegal Punishment from an International Perspective. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011.

Carrigan, William. The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central Texas, 1836–1916. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Carrigan William and Clive Webb. Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848–1928. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Goldsby, Jacqueline. A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

McGrath, Robert D. Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Pfeifer, Michael J. Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

———. The Roots of Rough Justice: The Origins of American Lynching. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Waldrep, Christopher. The Many Faces of Judge Lynch: Extralegal Violence and Punishment in America. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002.

———, ed. Lynch Law in America: A History of Documents. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Williams, Kidada. They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonials of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. New York: New York University Press, 2012.

Wood, Amy Louise. Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Web

"Fear Tactics: A History of Domestic Terrorism." NPR. Backstory with the American History Guys, September 14, 2012. http://backstoryradio.org/shows/fear-tactics-a-history-of-domestic-terrorism/.

Taylor, Quintard, ed. BlackPast.Org: An Online Reference Guide to African American History. http://www.blackpast.org/.

Without Sanctuary: Photographs and Postcards of Lynching in America. 2000–2005.

http://withoutsanctuary.org.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Rev. D. A. Graham, "Some Facts About Southern Lynching," Indianapolis Recorder, June 10, 1899, reprinted on BlackPast.Org: An Online Reference Guide to African American History, accessed October 9, 2013, http://www.blackpast.org/1899-reverend-d-graham-some-facts-about-southern-lynchings. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ida B. Wells, "Lynch Law in America," January 1900, accessed October 9, 2013, http://www.blackpast.org/1900-ida-b-wells-lynch-law-america. |

| 3. | See, for example, Matthew D. Lassiter and Joseph Crespino, eds., The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). |

| 4. | Manfred Berg and Simon Wendt, eds. Globalizing Lynching History: Vigilantism and Extralegal Punishment from an International Perspective (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011). |

| 5. | Christopher Waldrep, The Many Faces of Judge Lynch: Extralegal Violence and Punishment in America (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002). |