Overview

Sarah H. Hill reviews An Empire of Small Places: Mapping the Southeastern Anglo-Indian Trade, 1732–1795 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2012) by Robert Paulett.

Review

|

Understanding the creation of social spaces in an unfamiliar landscape is, according to Robert Paulett, a productive way to account for eighteenth-century developments in the American Southeast, particularly in Georgia. In his interesting but not entirely successful study of non-Native participants in the southeastern deerskin trade, Paulett uses the word "mapping" to convey their processes of coming to know and create ways to live in a particular place, a process that included imagination and adaptation as well as habitation.

Paulett finds that the geography of place varied with those who conceptualized, created, and utilized the "small spaces" they inhabited in the geography of the deerskin trade. The participants of his analysis are the British who bought and marketed deerskins and the boatment who transported trade goods in the American colonies. As a study of the trade from the perspective of non-Natives, the book provides a useful comparison to the work of ethnohistorians such as Kathryn Holland Braund and Claudio Saunt who focus on the Native American side of colonial contests over space. Moreover, while Saunt and Braund examined the contested spaces of houses and farms, Paulett looks at an entire river system, the Savannah, and its surrounding landscape.

In Paulett's study, the British traders, white and African boatmen, and colonial town merchants who shared the landscape of the deerskin trade created geographies that overlapped and were similar but not identical. Those connected to the trade conceptualized and developed a system of linked places that persisted through the upheavals of the eighteenth century and continually challenged British notions of order and control. Paulett asserts that incompatible mapping between British ideals and colonial reality led to the recurring pattern of misunderstanding and conflict that continually threatened the deerskin trade. His study threads its way through an era of turmoil, war, negotiation, environmental destruction, and English incursion on Native lands by concentrating on one arena where various populations charted their own courses.

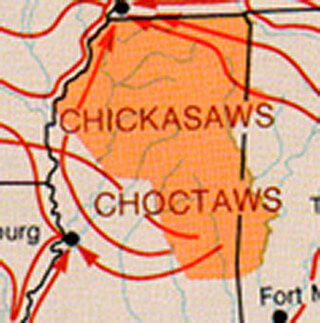

Paulett's study area is the trade route from Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina) up the Savannah River through Augusta, past several Creek Indian towns, and ending in the Chickasaw towns of present-day north Mississippi and west Tennessee. Temporally, the book covers most of the 1700s, beginning with the settlement of the Georgia colony and concluding with the aftermath of the American Revolution.

The empire of the book's title is a predominantly British vision of orderly settlements on the land of colonial Georgia, an imagined place that implied the English longing for control of lands and economies. The empire is also a landscape of commerce that developed locally and largely eluded British control at the hands of merchants, traders, and boatmen. By the end of the American Revolution the old geography had given way to what Paulett calls an "Empire of Liberty," a space imagined by white settlers who tried to redefine the region for themselves.

Each of the five chapters, as well as the introduction and conclusion, opens with a character sketch of a participant in the trade, providing immediacy, reinforcing the role of imagination in the creation of social space, and bringing the reader into the historical moment. Paulett begins with a consideration of James Oglethorpe on the banks of the Savannah River visualizing the possibilities of trade and concludes with a group of Augusta leaders eyeing the fencing on a former trader’s land. The sketches skillfully illustrate the power of spatial imagination while introducing the concept Paulett uses to organize his narrative.

|

| Edw. Crisp, Detail of A compleat description of the province of Carolina in 3 parts, the west part by Capt. Tho. Nairn, 1711. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 2004626926. |

|

| Henry Popple, A map of the British Empire in America with the French and Spanish settlements adjacent thereto, 1733. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 2009582407. |

|

| John Mitchell, A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements, 1755. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 74693187. |

Referencing literal as well as metaphorical maps and mapping, Paulett's first chapter persuasively establishes the tension between imperial efforts to control trade and local resistance expressed by the participants' point-to-point network of small places, a tension between the ideal and real. With no defined boundaries between southeastern occupants, Europeans drafted manuscript maps that reinforced imagined empires with drawings of a land whose features they did not know. In contrast to European spatial and static maps, those conceived and experienced by local Indians and traders were processional geographies of connected places. The book's cover presents an image of such geographies: the early-1700s Chickasaw map of friends and enemies denoted by a series of separate but linked circles. Although the eight other maps and two cartouches in the chapter are neither large nor clear enough to augment Paulett's discussion, they demonstrate that the early manuscript maps reveal the ambitions of the builders of American trade empires. He successfully repositions European maps as texts about power rather than information, and local maps as geographies of relationships.

In the following four chapters Paulett expands his argument to examine four arenas central to the deerskin trade: the Savannah River, the town of Augusta, trading paths connecting Augusta to Indian towns, and houses built by traders in Indian communities. Like blank parchments carefully inked by European cartographers, these venues were also spaces onto which various participants in the trade inscribed their maps. Each chapter looks at the competing and overlapping spatial concepts of the English, traders, merchants, and African American laborers, with some attention to Creek Indians. His review of diverse groups, settings, and activities highlights the everyday and personal elements of a global economy.

Paulett's spatial analysis is particularly illuminating when he examines a location, such as the trade town of Augusta, or discrete elements, such as maps. His discussion of Augusta details the ways English traders shaped a space to suit their needs rather than conforming to the imperialist vision of an orderly, fortified town. In contrast to other southern settlements, Augusta lacked town walls because the traders required an open town with easy and rapid communication among buyers and sellers, providers and purchasers. Individual trade houses were fortified and spaced a mile or so apart, which emphasized the dominance of trade rather than government or religion, and shaped the town in a unique configuration. As Paulett effectively shows, Augusta was a traders' space that articulated their economic, physical, and social authority.

|

| Archibald Campbell, Sketch of the northern frontiers of Georgia, extending from the mouth of the River Savannah to the town of Augusta, 1780. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 73694481. |

When addressing more fluid locations, Paulett's use of spaciality as an analytical framework is less effective. His chapter on the Savannah River, for example, seems unnecessarily encumbered by frequent assertions of space creation by the English, the traders, and the white and African boatmen. Certainly the corridor of water that was so essential to the deerskin trade carried different meanings to the trade's participants. Relying on his spatial paradigm, Paulett claims the English viewed rivers as empty spaces to be occupied and managed but could not accommodate their vision to the realities of the uncontrollable Savannah. Merchants relied on the river as a connector to one another and a link to the European world but experienced it only as infrequent, transitory visitors.

In contrast to both groups, according to Paulett, the white and enslaved African boatmen considered the Savannah a singular space in which they acted independently and experienced a measure of freedom. While his documentation and discussion of cross-cultural experiences expands our understanding of trading history, Paulett's imposition of spatial mapping onto the minds and experiences of African boatmen is not persuasive. Perhaps a boatman's momentary experience of freedom from plantation slavery inevitably led to his creation of a unique cultural space, but we have no evidence of his attendant development of identity derived from and expressive of that creation. Here, as in the chapter on the trading path, additional evidence is necessary to support the author's provocative assertions about the ways individuals conceptualized their experiences.

The book concludes with an overview of the American Revolution's dissolution of the trade that led to revised concepts of American geography. With little or no deerskin trade, new generations of Georgians could abandon the old trade geography to imagine a new, homogeneous kind of space with farms, settlements, and no Native Americans. Richly conceived and well expressed, the chapter documents the rise in upcountry newspaper articles about geographical boundaries, the growing public and academic interest in atlases and maps, and an increased frequency in use of the term "neighborhood" as indicators of Georgians' evolving American geography.

Robert Paulett has given us a refreshing consideration of life in the eighteenth-century deerskin trade. His focus on disparate groups occupying the same arena but living different experiences challenges us to reimagine the complexities of life among multiple cultures and changing landscapes. Reliance on a spatial framework enables him to shift his gaze and lead ours to see the agency of those groups in their effort to imagine, conceptualize, and shape their place in a shared world. Although Paulett's argument does not always succeed, his work adds new information and a different perspective to studies of the American South.

Recommended Resources

Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685–1815. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

Davis, Harold E. The Fledgling Province: Social and Cultural Life in Colonial Georgia, 1733–1776. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976.

Kane, Sharyn and Richard Keeton. In Those Days: African-American Life near the Savannah River. Atlanta, GA: National Park Service, 1994.

Saunt, Claudio. A New Order of Things: Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Stokes, Thomas L. The Savannah. New York: Rinehart, 1951.

Sweet, Julie Anne. Negotiating for Georgia: British-Creek Relations in the Trustee Era, 1733–1752. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005.

Links

Dubcovsky, Alejandra. "A Colonial Snapshot: Reading William Hammerton's 'Map of the Southeastern Part of North America, 1721'." Common-Place 12, no. 4 (July 2012), http://www.common-place.org/vol-12/no-04/tales/.

"Interview with Robert Paulett about his new book, An Empire of Small Places," Early American Places Blog, August 21, 2012, http://earlyamericanplaces.org/blog/?p=223.

"Georgia—Maps—Early Works to 1800," Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries, http://hmap.libs.uga.edu/hmap/search?year=1700;year-max=1799;f1-subject=Georgia--Maps--Early%20works%20to%201800.