Overview

Mark Auslander examines evidence that enslaved persons were involved in the construction of the original Smithsonian Building in Washington, DC. Many enslaved workers who labored at the Maryland quarry from which all the building's "freestone" or sandstone blocks were obtained had roots in enslaved families owned by Martha Custis Washington at Mt. Vernon.

Essay

And what erudition. He can even read stone. Only he never figures out that the veins in the marble of Diocletian's baths are the burst blood vessels of slaves from the stone quarries.—Zbigniew Herbert, "Classic."1Zbigniew Herbert, Collected Poems, 1956–1968 (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 141. Thanks to Allen Tullos for suggesting this apt quote.

|

| Carol M. Highsmith, Smithsonian Institution "Castle," Washington, DC, between 1980 and 2006. Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-HS503- 4211. |

Were enslaved persons involved in the construction of the original Smithsonian building, known today as "The Castle"? As is well established, enslaved African Americans worked on the construction of many buildings in antebellum Washington, DC, including the US Capitol and the White House, rarely receiving any monetary compensation.2The contributions of enslaved African American workers to the construction of the US Capitol are detailed in: William C. Allen, "History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol, Report by the Architect of the Capitol," June 1, 2005, https://emancipation.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/emancipation/publication/attachments/History_of_Slave_Laborers_in_the_Construction_of_the_US_Capitol.pdf. Was this true for the Smithsonian as well?

First, a little background. Slavery was an active presence in Washington during the years that the first Smithsonian building was under construction, from 1847 to 1855. To the immediate south of the Smithsonian grounds lay two of the most notorious 'slave pens' in the region, where persons of color, many of them kidnapped or arrested on the flimsiest of pretexts, were held under horrific conditions pending their sale to points south.3Kirk Savage evocatively writes, ". . . slave pens sat right on the edge of the Mall, and slave coffles—groups of slaves chained together—shuffled across the Mall's "waste" on their way to loading docks on the river. What L'Enfant had imagined as a glorious avenue leading to the equestrian image of Washington was now a scrubland pockmarked by the visible traces of the slave trade." Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington DC, The National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 46. One of these, the Williams House or "Yellow House" was located on the south side of "B" street (now Independence Avenue), more or less across the street from the present location of the Hirshhorn Museum. In 1850, Smithsonian regent Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy, remarked of this structure, "It is the house by which all must go who wish to reach the building of the Smithsonian Institution." Davis, a defender of slavery, claimed the building looked quite benign to him, but many abolitionist commentators circulated detailed narratives of the horrors that occurred within it.

|

| Balloon view of Washington, DC, Harper's Weekly, July 27, 1861, p. 476. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-71022. Smithsonian Institution Building can be seen at the top center east of the Potomac River and Virginia, Washington Canal visible, proceeding from the Potomac River due east and then southeast. |

A block away, at 7th and Maryland (the area now occupied by a park in front of Capital Gallery) stood the equally notorious Robey Tavern and Slave Pen. Coffles of chained enslaved people were regularly marched through the streets of downtown Washington, attracting a series of outraged petitions by anti-slavery advocates across the nation and inspiring passionate Congressional speeches by abolitionist representatives, appalled that slavery and the slave trade were openly conducted in the nation's capital. The spring that construction began in earnest on the Smithsonian building saw one of the most dramatic incidents in the local history of slavery; in April 1848, over seventy enslaved persons attempted to escape Washington on board the schooner Pearl. They were soon recaptured. Most were taken to the New Orleans slave markets to be sold into plantations in the Deep South; some were transferred back to Alexandria, Virginia, to be sold there. The freedom of the two most prominent escapees, the Edmonson sisters, was purchased by Reverend Henry Ward Beecher's Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York, where Reverend Beecher famously staged a mock "auction" of the two young women to raise funds.4Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape Attempt on the Potomac (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: Harper Collins, 2007). As part of the great compromise of 1850, centered on the Fugitive Slave Law, Congress in September 1850 prohibited the slave trade within the District of Columbia. Slavery itself continued in the District until April 16, 1862, when Congress provided that all slaveowners in the city would be compensated financially for the loss of their human property. Nonetheless, the Fugitive Slave Law was still, in principle, in force throughout the Civil War in the District of Columbia for enslaved persons who escaped from non-Confederate states and sought refuge in the city.

|

| A slave coffle in Washington, DC, possibly marching to auction, from William S. Dorr, Slave market of America, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19705. The J. W. Neal slave house was near the city's center market. |

Even free people of color did not feel safe on DC's streets. From 1852 until 1906, the celebrated free African American Solomon G. Brown had a remarkable career in many different departments of the Smithsonian. He was deeply trusted by the first Smithsonian secretary, Joseph Henry, who left the building under Brown's supervision during his absences from Washington. Yet, Brown, whose parents were free residents of Washington City, was clearly apprehensive of local slave merchants, who often kidnapped free persons of color and sold them into slavery. On July 21, 1858, six years after he began work at the Smithsonian, Brown took the precautionary step of obtaining a certificate of freedom, in which his white friend and former employer at the post office, Lambert Tree, swore in front of a justice of the peace that Brown had always been free.

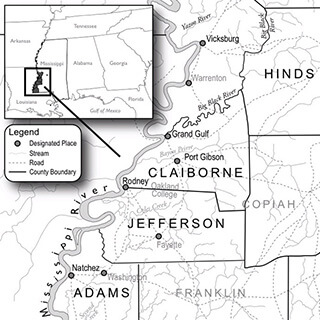

During this early period, did enslaved people actively contribute to the making of the Smithsonian? Our strongest evidence comes from records associated with the Seneca quarry, about twenty-three miles up the C & O Canal from the capital city. After extensive field research and laboratory tests on local stone deposits, geologist David Dale Owen, brother of Congressman Robert Dale Owen, head of the Smithsonian building committee, recommended that the Potomac "freestone" in the vicinity of Seneca was the most promising building material. The quarry's owner, John Parke Custis Peter, wrote the building committee on March 22, 1847 that he would charge "twenty-five cents a perch for all stone intended for face or cut work, and twelve and a half cents per perch for all calculated for backing or rubble work."

|

| Simon J. Martenet, Detail of Martenet and Bond's Map of Montgomery County, 1865. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 2002620533. A white box shows John P. C. Peter's sandstone quarry and residence at Seneca Mills, just north of the Potomac River in Virginia. |

John P. C. Peter, the quarry owner, was a great-grandson of Martha Custis Washington, the wife of George Washington, and a slaveowner. Present-day African American residents of Seneca share oral historical accounts, passed down through the generations, that before the Civil War, the quarry was mainly worked by enslaved men.5It would appear that few free persons, white or African American, labored in the quarry during this period. The 1850 census, enumerated two years after the Smithsonian sandstone was quarried, records only one white stonecutter residing in the entire Medleys District of Montgomery County, Maryland. Charlesworth Wood, age forty seven, born in England, lived adjacent to the widow of John P. C. Peter and her new husband Rev. Charles Nourse. Of the approximately one hundred free persons of color residing in the Medleys district in 1850, nearly all are accounted for in terms of employment in farm labor or other trades, such as plastering. It thus seems a fair conclusion that, as oral history accounts by Seneca's current African American community members attest, the majority of labor in the quarry was done by enslaved men possessed by quarry owner John Parke Custis Peter, or by slaves that he rented from fellow slaveowners in the area. (After the Civil War, the quarry was worked by Irish and African American laborers.) The 1840 census records that John P. C. Peter, then residing at his mansion Montevideo, owned twenty-three slaves.

The "back story" of these enslaved people is in itself a fascinating chapter in early American history. The Peter slaves were closely connected, through kinship and common servitude, with the enslaved people owned by George Washington and Martha Custis Washington. Around 1795, eleven families of enslaved people were transferred to Martha Custis Washington's grand-daughter Martha Custis Peter, as her "patrimony" or "dower slaves." In the ensuing months, Mrs. Peter's husband, the prominent Georgetown merchant Thomas Peter, sold away many of these slaves, realizing several thousands dollars in revenue. It appears that the proceeds from some of these slave sales helped to pay for the construction of Tudor Place in Georgetown, one of the nation's most magnificent private residences. In his book, An Imperfect God, historian Henry Wiencek speculates that George Washington's decision to free his own slaves in his will was partly inspired by these slave sales, which broke up enslaved families related to the Mount Vernon enslaved community.6Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003), 335–339. Manumission was to be effective following the death of his wife, Martha Custis Washington.

After Mrs. Washington's death in 1802, a number of her slaves at Mount Vernon were inherited by Martha Custis Peter, adding to the Peter family holdings. (George Washington's will stipulated that his slaves would be freed upon Martha’s death. The will did not impact the legal status of the “dower slaves” which Martha had brought into their 1759 marriage, who were eventually passed onto her first husband’s heirs.)

Over the next several decades, some of the remaining enslaved people in "Mrs. Peter's patrimony," and their offspring, were transferred to the son of Thomas and Martha Custis Peter, John Parke Custis Peter, owner of a farm and quarry in Seneca, near lock twenty-four of the C & O Canal. (An 1835 court petition notes that prior to the death of Thomas Peter, he transferred forty-six slaves to his two sons, John Parke Custis Peter and George Washington Peter, and a family associate.)7The use of enslaved labor at the Peter family’s Seneca quarry definitively dates to as early as 1823. In that year the Federal government undertook excavations at Seneca quarry, then under the ownership of Thomas Peter, the father of John P.C. Peter. A ledger book recording payments for this enterprise has been located in the National Archives by historian Garrett Peck, who has generously shared its contents. The ledger book indicates the presence of at least eighteen enslaved workers in Seneca quarry. Three men, Benjamin Delahey, Benjamin Bird, and “James,” are identified as “Boy.” Thirteen men--Alexander, Frank, Harry, Hall, Hillary , Ishmael, Luke, Martin, Nace (evidently also referred to as Ignatius), Rezin, Salsbury, Thomas, William--are identified only by first name. Of those thirteen, two are specifically identified by race, “Negro Martin” and “Negro Frank.” It is not clear if these enslaved men were directly compensated for their labor in the quarry or if only their owners were paid. In the case of two workers, Harry and a Leonard Mattingly, the name, “Anthony B. Smith,” is listed besides their names, suggesting that Mr. Smith may have been their owner, renting them out for quarry labor. Rachael Cheney is also listed as a “cook”; it is not clear is she was enslaved or free. (For more information on Seneca quarry, and a discussion of this ledger book, see the forthcoming book, Garrett Peck, Seneca Castle and the Smithsonian Castle, Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2013.)

Two of the enslaved quarry workers may be the same as persons listed in the 1795 inventory of Mrs. Peter’s Patrimony, currently held at Tudor Place. William, who worked at the quarry in April and May 1823, may be the same person as Will, age seventeen, son of Bob and Sal, in the 1795 list. Harry, who worked in the quarry in June 1823, may be the same person as the seven-year-old Harry, son of Joe and Patty, in the 1795 list.

Through a "lucky" historical accident we can determine the names of the enslaved people owned by John P. C. Peter at the time he sold the Smithsonian the sandstone for the Castle. Since he died without a will in early 1848, the Montgomery County Court of Orphans ordered an inventory of his property. This document records the names, ages, and monetary values of the twenty-four people John Peter held as human property at the time of his death:

Inventory of the Goods chattels and personal estate of John P C Peter, late of Montgomery Co, decd.

Negro man Sandy over 50 years [valued at] $175

Negro man Dave over 50 years $200

Negro man George (?) over 50, $225

Negro man John over 50, $225

Negro man Daniel 33, $410

Ned, 30, $500

Morris (?) 24, $600

George? (?) 14, $350

Sandy, 7, $200

Joseph very old, $100Woman Celia old, (?) $40

Betsey and child, (?) $400

Harriet and child, (?) $350

Hinta (?) $100

Eliza and 3 children, (?) $625

Anna (?) $150

Mary 35, (?), $200

Girl Mary 12, (?) $250

Cornelia, (?) 150

Of these persons, it seems probable that two or more had numbered among the "Dower slaves" brought by Martha Dandridge Custis into her marriage to George Washington in 1759. These slaves labored at Mount Vernon and its associated farms, prior to the death of Martha Washington in 1802. 8Strictly speaking, Martha Custis Washington did not own the dower slaves, which were to be held by the Custis Estate until her son, John “Jacky” Custis, attained majority and assumed ownership. Since John died during the American Revolution, these slaves then passed to his heirs, including Martha Custis Peter, the wife of Thomas Peter of Georgetown. Upon the death of her first husband in 1757, Martha was guaranteed life use of one third of her husband’s lands and slaves. This dower share was the source of much of Mount Vernon's income, resources which in turn made it possible for George Washington to expand Mount Vernon’s land and slave holdings. For a more detailed discussion, see Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003). Our principal evidence for this is the detailed 1799 inventory made of the Mount Vernon slaves at George Washington's command. The most likely matches are as follows:

The man Sandy, listed as "over 50" in the 1848 inventory, could be the eighteen month old Sandy, son of Ann, listed in 1799 as residing in the Mount Vernon Mansion House.

George, "over 50" in 1848, could well be the one-year-old George, residing in the Dogue Run Farm, brother of Barby, Abbay, Hannah, and son of Sall T.

Davy, "over 50" in 1848, might be the six-year-old Davy residing in 1799 in the River Farm, son of Cornelia, and brother of Lewis, four, and Alec, two. Or he might be the same person as the eight-year-old Davy, Son to Rachel, living in the Union Farm.

John, "over 50" in 1848, might be in 1799 either John, age unknown, son to Mima and brother to Randolph, living in the Mount Vernon Mansion House, or John, age sixteen son of the sixty-two-year-old Betty, residing in the Union Farm.

Celia, listed simply as "old' in 1848, might be the same person in the 1799 inventory as Cecelia, age fourteen, unmarried, in the River Farm. Cecilia was the daughter of Agnes, who was married to the carpenter Sambo; Cecilia was thus the sister or half sister of Heuky, age seventeen, Anderson, age eleven, and Guy, age two.

Finally, Eliza, listed with her three children in 1848, might have been the same person as Elizabeth, age nine, Daughter to Doll, at the Union Farm (sister to Sucky and Elias) or she might have been Eliza, daughter to Charlotte, no age given, residing in the Mount Vernon Mansion House. She was the sister of Elvey and Jenny.

In any event, after 1802 about one quarter of Martha Washington's slaves from the Mount Vernon farms, amounting to about thirty people, were transferred to Martha and Thomas Peter in Georgetown. At some later point many were moved out to the Peter family holdings in Seneca, which included the Bull Run sandstone quarry.9There are four possible matches between the names in the 1848 Peter estate inventory, and a list of slaves brought to the marriage by Martha Parke Custis in 1795, held in the Archives of Tudor Place in Georgetown. (Most of these 1795 slaves would appear not to have come from Mount Vernon, but rather from the outlying Custis plantations in York and New Kent.) The possible matches are as follows: Joseph, “very old” in the 1848 inventory, may be the same person as Joe, age twenty-seven in 1795, the husband of Patty and father of Tom and Harry; George, over fifty in 1848, may be the same person as George, age seven, in 1795, the son of Bob and Sall ; Anna (age not given) in the 1848 inventory may be the same person as the four year old Anna (child of Molly) or the eight year old Anna (child of Rose) in 1795; John, “over fiffty” in 1848, may be the same person as the two year old John in 1795. Many thanks to Henry Wiencek for generously sharing his transcription of the 1795 inventory. It would appear that a number of Thomas and Martha Peter's slaves were transferred to John Parke Custis Peter well before Thomas' death. A year after Thomas died, an 1835 petition seeks to recover debts from his estate. The plaintiffs allude to an 1820 deed through which Thomas Peter transferred forty-six slaves to John Parke Custis Peter and other persons, along with six hundred acres of land in Montgomery County.10Loren Schweninger, ed., Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Series II, Petitions to Southern County Courts, 1775–1867 (Bethesda, MD: LexisNexis, 2005), microform. The petition asserts that Thomas Peter on "[illeg.] day of August in the year 1820 did convey to the said Robert Pick and P. P. C. Peter part of a tract of land called Conclusion containing about six hundred acres at that time in the possession of said Thomas Peter, and the management of one Wm Robbin and also forty six negroes the slaves of said Thomas who are named in the same copy, a copy of which is herewith exhibited marked No. 3." As of this writing I have not been able to locate the August 1820 deed. Records indicate that John Peter in the 1820s and 1830s continued to hold multiple residences, in Georgetown, Tenleytown in Washington, DC, and Seneca in Montgomery County, Maryland, and that he held slaves at these locations.

|

| "150 Dollars Reward," Daily National Intelligencer, July 28, 1831. John P. C. Peter offered a reward for the return of three enslaved men, who had escaped from Seneca Mill. |

It seems likely that a number of the adult men enumerated in the 1848 inventory worked in the Seneca quarry during the months the triassic sandstone (ironically, often termed "freestone") blocks were quarried for the Smithsonian contract from the rockface and milled in preparation for barge transport down the canal to the Smithsonian building site, evidently in the spring of 1848.

We can surmise that work in the quarry was extremely difficult, but we know very little of the precise conditions under which the Peter slaves worked and lived. Standing near the Montevideo mansion are remnants of a stone slave quarters, in more recent years used as a youth hostel; we do not know if the enslaved quarry workers resided there or closer to the quarry, near the canal and the Potomac River. From a runaway slave advertisement placed by John P. C. Peter in 1831 we know that three enslaved men—Peter Bowman, George Bowman, and Beverly Davis—escaped from the Seneca property, presumably heading for Pennsylvania and freedom. (None of these three are listed in the 1848 inventory, so it is possible that their escape attempt was successful.11Perhaps twenty-three-year-old George Boman, mentioned in the 1831 Runaway Ad, is the same person as the "George," over fifty years of age, listed in the inventory of John P. C. Peter's estate.

Many descendants of Seneca African American quarrymen continue to live in the Seneca area near Darnestown and Germantown in Montgomery County, and continue to pass on stories of the quarry and the canal.12After Peter's death, some slaves from the John P. C. Peter estate were retained by Peter's widow Elizabeth and her second husband, the clergyman and educator Charles Nourse. The Nourses relocated to Virginia, Elizabeth's home state, in the late 1850s with several slaves. (Rev. Nourse served as a Confederate courier during the Civil War and was for a period imprisoned by the Union military in Washington, DC, until he was exchanged for pro-Union detainees.) Other slaves from the estate were apparently conveyed to John P. C. Peter's children as they reached the age of majority. Still others may have been sold off to settle the estate's debts or raise cash for other purposes. At least two of the enslaved people listed in the 1848 inventory evidently obtained their freedom soon after the death of John P. C. Peter. In the 1850 census for Medleys, Montgomery County, Maryland, a free woman of color, Harriet Beale, age thirty-one, and her thirteen-year-old daughter Nelly, are listed as living next door to Elizabeth Nourse, the widow of John P. C. Peter and her new husband, Charles Nourse. These Beales presumably are the same two people as "Harriet and child", valued at $350.00 in the 1848 slave inventory of the late John P. C. Peter's estate. Harriet continued to reside in Medleys as a freewoman until at least 1860. Her daughter Nelly appears to have married a George Green and settled after the Civil War in Sandy Spring, on the other side of Gaithersburg from the Medleys district. I recently participated in worship services with many of these descendants at the Seneca Community Church, where stories of African American contributions to the first Smithsonian building are proudly remembered.

|

| Edward Sachse, Detail of Panoramic view of Washington City from the new dome of the Capitol, looking west, published by E. Sachse and Company, c. 1856. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-02582. |

After they had been milled, the blocks of Seneca sandstone were transported down the canal to Georgetown and along the canal that then ran beside the National Mall.13Members of the African American descendant community in Seneca, Maryland (associated with the Seneca Community Church congregation) recall oral historical accounts, passed down from elders, that enslaved people at the quarry were tasked with transporting quarried stone down the canal to Washington, DC, and to the Smithsonian site. I have not been able to confirm this assertion from the extant documentary record. (The rather isolated terrain on which the Smithsonian was located, bounded by the canal and the Potomac River, was often referred to as "the Island.")14At the time of the construction of the original Smithsonian building (1847–1855). Pierre L'Enfant's original plan that the Mall would serve as a grand national park had not yet been realized. The Mall area was used for farming, horticulture and the storage of lumber and trash; the area on which the Castle was built was a marshy floodplain, difficult to traverse. The Tiber Creek, running along the Mall's northern boundary, had been transformed into the Washington Canal, running east from the Potomac River (where it entered the city at the area of the present-day "Watergate" complex). Present-day Constitution Avenue is built atop the remnants of the old Washington Canal, which was filled in, in the early 1870s, as a health and sanitation hazard. See: Richard Longstreth, ed. The Mall in Washington, 1791–1991, 2nd edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003); Kenneth Hafertepe, America's Castle: The Evolution of the Smithsonian Building and its Institution, 1840–1878 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984); Cynthia Field, Richard Stamm, and Heather Ewing, The Castle: An Illustrated History of the Smithsonian Building, 2nd edition (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2012). Once the materials reached the Smithsonian site, did enslaved workers aid in the construction of the new building and the creation of the Smithsonian grounds?

While many antebellum US institutions, including colleges, universities, and railroads, owned slaves, the Smithsonian Institution never owned human property. However, there is some suggestive evidence that contractors compensated by the Institution may have rented enslaved persons for labor. For instance, according to the Smithsonian Day Book, in which the Institution's financial expenditures were recorded, a payment was made on January 15, 1850 in reference to the labor of hauling trees from Georgetown and replanting them on the Smithsonian grounds:

|

| Ledger entry for January 15, 1850, Smithsonian Institution Day Book, 1846–1856, p. 578. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives. On Jan. 15, 1850, either the white gardener and florist John Howlett or Jonathan Clark were compensated for the labor (one half day each) of "two colored men", at a total of one dollar, working on the Smithsonian grounds. |

Digging trees for Smithsonian

3 days self & man, $2

1/2 day each for 2 col'd (colored) men, $1

3 days excavating trees self and man, $6

We cannot be sure if "man" in this entry refers to a free or enslaved person, but given the usage of the day, "col'd" or "colored" most likely refers to enslaved men. The ledger entry is a little ambiguous as to who precisely was compensated for this labor. It falls under a larger entry for John Howlett, an English-born gardener and florist who worked for the Smithsonian, but concludes with a line on which the word "for" is struck out and replaced with "by", followed by "Jno. Clark, $36.50," evidently indicating that a Jonathan Clark was compensated for the above-mentioned labor by the "colored men."

The gardener John Howlett is not listed as a slaveowner in the 1850 slave schedule in Washington. A white man identified in the 1850 slave schedule for the District of Columbia as "J. Clarke" (Ward 3, Washington) is listed as owning one eighteen-year-old male slave. The Day Book, under February 16, 1850 next makes reference to a "W. Clark" arranging for a "driver" and "man" to haul trees from Georgetown to the Smithsonian Grounds.15Smithsonian Institution Day Book, 1846–1856, p. 578. In 1850, William Clarke of Washington, DC, owned eight slaves, including four males between the ages of sixteen and sixty. It is possible that one or more of these enslaved men was tasked with hauling trees from Georgetown.16It appears possible to reconstruct the names of these enslaved men. The slaveowner William Clark died July 7, 1855. In 1862, his widow petitioned for compensation for a group of slaves that had been freed by the act of Congress. These included three adult men, whose ages roughly match with those of the unnamed male slaves enumerated in the 1850 slave schedule for the William Clark household: Benjamin Marler, age seventy; William Butler, thirty-two; Frank Joyce, thirty. It seems quite possible that one or more of these men, as slaves, hauled the trees to the Smithsonian grounds. At least two of these men continued to live in Washington: Eight years later, in the 1870 census, William Butler, age forty, is listed as a brick maker, living near seventh street. Residing in the same neighborhood is Frank Joyce, "expressman," age thirty-eight. In the mid-nineteenth century, an "expressman" referred to a wagon driver; speculatively, perhaps Frank Joyce was the "driver" referred to in the Day Book's entry for February 16, 1850.

Also in January 1850, the Smithsonian compensated the upholsterer D. A. Baird for the work of "a man 2 1/2 days papering screens @ $2," for a total of $5.00. In July of the same year, contractor William Harrover, working on the building's east wing, installing air flues and pipes, billed for the following labor, "three days work man and boy" at the rate of $2.75 per day for a total of $8.25. William H. Harrover, born in Virginia, was a well-known Washington stove and hardware merchant. Although William Harrover is not listed as a slaveowner, a David Harrover, evidently his brother or cousin, resided in nearby Fairfax, Virginia, and in 1850 owned a thirty-five-year-old man and a twelve-year-old boy. Perhaps William rented these two "colored men" from David and was paid by the Smithsonian for this expense.

|

| Old Smithsonian Institution Building (now known as the "Castle"), in upper left, viewed from downtown Washington. Washington Canal visible in upper right, c. 1855. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives. |

The principal contractor for the Smithsonian construction project was the Scottish stonecutter and master builder Gilbert Cameron. Cameron was not a slaveowner but it is possible that he or his subcontractors rented the labor of enslaved people during the 1847–1855 period. Some payments to Cameron are suggestive along these lines. On May 12, 1851, he was reimbursed for the work of "16 1/2 days work bricklayers at $2.50, 2 days carpenters at $3.00 per day and 16 1/2 days work of laborers, at 1.25 per day" and "8 days stonecutters" at 2.00 per day." In November of the same year Cameron was paid for "12 days laborers putting in coal," at $1.25 per day. It is possible, given the nature of the Washington labor market at the time, that some of these skilled and unskilled laborers were enslaved. (Many District of Columbia slaveowners during this period earned significant income from renting out slaves with artisinal skils.)

|

| The Smithsonian Institution, from a stereograph, 1859. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-55101. |

In 1862, by a special act of Congress, all enslaved persons within the District of Columbia were manumitted, and their owners financially compensated for the loss of their human property. Free African American workers at the Smithsonian, however, continued to face racial discrimination and hostility. Consider an event that took place soon after a fire swept through the Smithsonian building on January 24, 1865, collapsing the roof and severely damaging the interior. Professor Joseph Henry, the Smithsonian secretary, observed in his desk diary on January 27: "Today, a large number of carpenters commenced the putting on the roof—a gang of colored men were also engaged to assist in handling the boards—but as soon as the Irishmen saw the negroes they all cleared out without giving notice." We do not know the identities of these free African American workers, whose presence so upset the Irish carpenters, but we presume they continued with the repairs of the building roof.

Solomon Brown, his colleague James Gant (who worked at the Smithsonian from the 1850s until 1900), and these unnamed African American restorers of the Castle roof inaugurated a long and proud history of free African American employment at the Smithsonian, a history that dates from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day. In addition to these free persons of color, we should recognize the likely contributions of enslaved persons, names known and unknown, to the early years of the Institution. The evidence does seem strong that at least some of the enslaved African American men listed above—the adult men Joseph, Sandy, Dave, George, John, Daniel, Ned, Morris, and perhaps the fourteen-year-old George—labored to extract and mill the sandstone blocks that still adorn the Castle building. The unnamed "two colored men" and perhaps the other "men" and "boy" listed in the Daybook in 1850–51 may quite likely have been enslaved as well.

|

| Early photograph of Washington, DC, from the Capitol looking west-southwest, c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-127632. |

In 1862, the very year that all enslaved men and women in the District of Columbia were at last freed, the Smithsonian was at the heart of the bitter national debate over slavery. Abolitionist lectures in the Smithsonian lecture hall, by such prominent figures as Horace Greeley and Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, were fiercely denounced by pro-slavery advocates, including those on the Union side of the Civil War. Secretary Joseph Henry, no friend of abolitionism, became infuriated when the Washington Lecture Association attempted to schedule a lecture in the Castle by Frederick Douglass. Secretary Henry blocked Douglass' lecture and then moved to ban all subsequent public lectures at the Institution for the remainder of his tenure.17The controversy over the Washington Lecture Series is detailed in Michael F. Conlin, "The Smithsonian Abolition Lecture Controversy: The Clash of Antislavery Politics with American Science in Wartime Washington," Civil War History 48, no. 4 (December 2000), 301–323. Secretary Henry, a firm believer in scientific racism, argued for the natural inferiority of persons of African descent. A close friend of Senator John C. Calhoun (no friend of the Smithsonian), Henry maintained that blacks could only co-exist with whites in the United States if maintained in a state of slavery. During the Civil War, Henry attempted to maintain the Smithsonian's neutrality in the conflict, refusing to authorize the flying of the Stars and Stripes over the Castle building. He was suspected in some Union quarters of pro-confederate sympathies; he did, however, serve as a trusted scientific and technical advisor to Lincoln on military matters throughout the War. Henry's second in command and successor at the Smithsonian, Spencer Baird, was a noted anti-racist and served as an important advocate for African American Smithsonian employees during his tenure as Secretary (1878–1887).

In 1902, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his employment at the Smithsonian Institution, Solomon Brown composed a poem, looking back on his many years of service. The poem concluded:

Since eighteen hundred and fifty-two,

This may seem far back to you;

But much has passed I have not told-

Then I was young but now I'm old,

But still I am observing.

What, we may wonder, did Brown, a constant and keen observer of all aspects of the Institution, not tell us in the poem and in his other written records? Working at the Smithsonian for a decade before Emancipation came to the District of Columbia, did he observe enslaved men and women working at the Institution? Although we may never know for certain, we can with confidence assert that the Smithsonian, while formally dedicated to the highest principles of democracy and scientific inquiry celebrated by the young republic, emerged out of an economic and cultural context predicated on slave labor. The legacies of this contradictory history remain with us to this day at the Smithsonian and in our nation. In seeking to uncover, and to honor, the early contributions of enslaved laborers to the institution, we hold up a mirror to ourselves, confronting enduring challenges of race, power, and the quest for human liberation.

This essay was updated on December 18, 2012 to incorporate corrections.

Acknowledgments

Research for this project was supported by a senior fellowship from the Smithsonian's Office of Fellowships and Internships at the National Museum of African Art, and by the Office of the Dean, College of the Sciences, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington. The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following persons and organizations: Pamela Henson, Historian, and the staff at the Smithsonian Institution Archives; Rick Stamm, Keeper, Castle Collection, Architectural History and Historic Preservation Division, Smithsonian Institution; Wendy Kail, archivist, Tudor Place Foundation; Julie Miller, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress; Special Collection Archivist Jerry A. McLeod and staff at the Washingtonia Division, Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library; the Washington Historical Society; the staff of the Jane C. Sween Library, Montgomery County Historical Society; and Rev. Kenneth H. Nelson and the congregation of Seneca Community Church, Germantown, Maryland. Special thanks to Lonnie Bunch, Rex Ellis, John Franklin, Johnnetta Cole, Mary Jo Arnoldi, Christine Mullen Kreamer, Jessica Martinez, Fath Davis Ruffins, Ellen Schattschneider, Judith Knight, Ruth Auslander, and Tracey Cones for their guidance, support, and encouragement in this project. This essay is dedicated to the memory of the late Herb Shapiro (1929–2012), who always encouraged us to uncover legacies of slavery, liberation struggles, and African American historical agency in the most diverse of spaces.

Discussion

To join the discussion on this piece, please visit "Seneca Quarry," a response on the Southern Spaces blog by Garrett Peck, and add your comment.

Recommended Resources

Burleigh, Nina. The Stranger and the Statesman: James Smithson, John Quincy Adams, and the Making of America's Greatest Museum, The Smithsonian. New York: Harper Collins, 2004.

Davis, Damani. "Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation's Capital: Using Federal Records to the Explore the Lives of African American Ancestors," Prologue Magazine (National Archives) 42, no. 1 (Spring 2010), http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2010/spring/dcslavery.html

Ewing, Heather. The Lost World of James Smithson: Science, Revolution, and the Birth of the Smithsonian. New York: Bloomsbury, 2007.

Harrison, Robert. Washington during Civil War and Reconstruction: Race and Radicalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Holland, Jesse J. Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African-American History In and Around Washington, DC. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2007.

Rhees, William Jones, ed. The Smithsonian Institution. Documents Relative to its Origin and History. 1836–1899. Vol. 1, 1835–1887. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1901.

Roig-Franzia, Manuel. "Researcher Finds Slaves Quarried Sandstone Used to Build Smithsonian Castle," The Washington Post, December 12, 2012. http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2012-12-12/lifestyle/35789178_1_slaves-quarry-site-smithsonian-officials.

Links

Legacy of Slavery in Maryland, Maryland State Archives

http://www.mdslavery.net.

Smithsonian History, Online Exhibits, Smithsonian Institution Archives

http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits.

Smithsonian Institution Archive Collection

http://siarchives.si.edu/collections.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Zbigniew Herbert, Collected Poems, 1956–1968 (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 141. Thanks to Allen Tullos for suggesting this apt quote. |

|---|---|

| 2. | The contributions of enslaved African American workers to the construction of the US Capitol are detailed in: William C. Allen, "History of Slave Laborers in the Construction of the United States Capitol, Report by the Architect of the Capitol," June 1, 2005, https://emancipation.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/emancipation/publication/attachments/History_of_Slave_Laborers_in_the_Construction_of_the_US_Capitol.pdf. |

| 3. | Kirk Savage evocatively writes, ". . . slave pens sat right on the edge of the Mall, and slave coffles—groups of slaves chained together—shuffled across the Mall's "waste" on their way to loading docks on the river. What L'Enfant had imagined as a glorious avenue leading to the equestrian image of Washington was now a scrubland pockmarked by the visible traces of the slave trade." Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington DC, The National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 46. |

| 4. | Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape Attempt on the Potomac (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: Harper Collins, 2007). As part of the great compromise of 1850, centered on the Fugitive Slave Law, Congress in September 1850 prohibited the slave trade within the District of Columbia. Slavery itself continued in the District until April 16, 1862, when Congress provided that all slaveowners in the city would be compensated financially for the loss of their human property. Nonetheless, the Fugitive Slave Law was still, in principle, in force throughout the Civil War in the District of Columbia for enslaved persons who escaped from non-Confederate states and sought refuge in the city. |

| 5. | It would appear that few free persons, white or African American, labored in the quarry during this period. The 1850 census, enumerated two years after the Smithsonian sandstone was quarried, records only one white stonecutter residing in the entire Medleys District of Montgomery County, Maryland. Charlesworth Wood, age forty seven, born in England, lived adjacent to the widow of John P. C. Peter and her new husband Rev. Charles Nourse. Of the approximately one hundred free persons of color residing in the Medleys district in 1850, nearly all are accounted for in terms of employment in farm labor or other trades, such as plastering. It thus seems a fair conclusion that, as oral history accounts by Seneca's current African American community members attest, the majority of labor in the quarry was done by enslaved men possessed by quarry owner John Parke Custis Peter, or by slaves that he rented from fellow slaveowners in the area. |

| 6. | Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003), 335–339. |

| 7. | The use of enslaved labor at the Peter family’s Seneca quarry definitively dates to as early as 1823. In that year the Federal government undertook excavations at Seneca quarry, then under the ownership of Thomas Peter, the father of John P.C. Peter. A ledger book recording payments for this enterprise has been located in the National Archives by historian Garrett Peck, who has generously shared its contents. The ledger book indicates the presence of at least eighteen enslaved workers in Seneca quarry. Three men, Benjamin Delahey, Benjamin Bird, and “James,” are identified as “Boy.” Thirteen men--Alexander, Frank, Harry, Hall, Hillary , Ishmael, Luke, Martin, Nace (evidently also referred to as Ignatius), Rezin, Salsbury, Thomas, William--are identified only by first name. Of those thirteen, two are specifically identified by race, “Negro Martin” and “Negro Frank.” It is not clear if these enslaved men were directly compensated for their labor in the quarry or if only their owners were paid. In the case of two workers, Harry and a Leonard Mattingly, the name, “Anthony B. Smith,” is listed besides their names, suggesting that Mr. Smith may have been their owner, renting them out for quarry labor. Rachael Cheney is also listed as a “cook”; it is not clear is she was enslaved or free. (For more information on Seneca quarry, and a discussion of this ledger book, see the forthcoming book, Garrett Peck, Seneca Castle and the Smithsonian Castle, Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2013.)

Two of the enslaved quarry workers may be the same as persons listed in the 1795 inventory of Mrs. Peter’s Patrimony, currently held at Tudor Place. William, who worked at the quarry in April and May 1823, may be the same person as Will, age seventeen, son of Bob and Sal, in the 1795 list. Harry, who worked in the quarry in June 1823, may be the same person as the seven-year-old Harry, son of Joe and Patty, in the 1795 list. |

| 8. | Strictly speaking, Martha Custis Washington did not own the dower slaves, which were to be held by the Custis Estate until her son, John “Jacky” Custis, attained majority and assumed ownership. Since John died during the American Revolution, these slaves then passed to his heirs, including Martha Custis Peter, the wife of Thomas Peter of Georgetown. Upon the death of her first husband in 1757, Martha was guaranteed life use of one third of her husband’s lands and slaves. This dower share was the source of much of Mount Vernon's income, resources which in turn made it possible for George Washington to expand Mount Vernon’s land and slave holdings. For a more detailed discussion, see Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003). |

| 9. | There are four possible matches between the names in the 1848 Peter estate inventory, and a list of slaves brought to the marriage by Martha Parke Custis in 1795, held in the Archives of Tudor Place in Georgetown. (Most of these 1795 slaves would appear not to have come from Mount Vernon, but rather from the outlying Custis plantations in York and New Kent.) The possible matches are as follows: Joseph, “very old” in the 1848 inventory, may be the same person as Joe, age twenty-seven in 1795, the husband of Patty and father of Tom and Harry; George, over fifty in 1848, may be the same person as George, age seven, in 1795, the son of Bob and Sall ; Anna (age not given) in the 1848 inventory may be the same person as the four year old Anna (child of Molly) or the eight year old Anna (child of Rose) in 1795; John, “over fiffty” in 1848, may be the same person as the two year old John in 1795. Many thanks to Henry Wiencek for generously sharing his transcription of the 1795 inventory. |

| 10. | Loren Schweninger, ed., Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Series II, Petitions to Southern County Courts, 1775–1867 (Bethesda, MD: LexisNexis, 2005), microform. The petition asserts that Thomas Peter on "[illeg.] day of August in the year 1820 did convey to the said Robert Pick and P. P. C. Peter part of a tract of land called Conclusion containing about six hundred acres at that time in the possession of said Thomas Peter, and the management of one Wm Robbin and also forty six negroes the slaves of said Thomas who are named in the same copy, a copy of which is herewith exhibited marked No. 3." As of this writing I have not been able to locate the August 1820 deed. |

| 11. | Perhaps twenty-three-year-old George Boman, mentioned in the 1831 Runaway Ad, is the same person as the "George," over fifty years of age, listed in the inventory of John P. C. Peter's estate. |

| 12. | After Peter's death, some slaves from the John P. C. Peter estate were retained by Peter's widow Elizabeth and her second husband, the clergyman and educator Charles Nourse. The Nourses relocated to Virginia, Elizabeth's home state, in the late 1850s with several slaves. (Rev. Nourse served as a Confederate courier during the Civil War and was for a period imprisoned by the Union military in Washington, DC, until he was exchanged for pro-Union detainees.) Other slaves from the estate were apparently conveyed to John P. C. Peter's children as they reached the age of majority. Still others may have been sold off to settle the estate's debts or raise cash for other purposes. At least two of the enslaved people listed in the 1848 inventory evidently obtained their freedom soon after the death of John P. C. Peter. In the 1850 census for Medleys, Montgomery County, Maryland, a free woman of color, Harriet Beale, age thirty-one, and her thirteen-year-old daughter Nelly, are listed as living next door to Elizabeth Nourse, the widow of John P. C. Peter and her new husband, Charles Nourse. These Beales presumably are the same two people as "Harriet and child", valued at $350.00 in the 1848 slave inventory of the late John P. C. Peter's estate. Harriet continued to reside in Medleys as a freewoman until at least 1860. Her daughter Nelly appears to have married a George Green and settled after the Civil War in Sandy Spring, on the other side of Gaithersburg from the Medleys district. |

| 13. | Members of the African American descendant community in Seneca, Maryland (associated with the Seneca Community Church congregation) recall oral historical accounts, passed down from elders, that enslaved people at the quarry were tasked with transporting quarried stone down the canal to Washington, DC, and to the Smithsonian site. I have not been able to confirm this assertion from the extant documentary record. |

| 14. | At the time of the construction of the original Smithsonian building (1847–1855). Pierre L'Enfant's original plan that the Mall would serve as a grand national park had not yet been realized. The Mall area was used for farming, horticulture and the storage of lumber and trash; the area on which the Castle was built was a marshy floodplain, difficult to traverse. The Tiber Creek, running along the Mall's northern boundary, had been transformed into the Washington Canal, running east from the Potomac River (where it entered the city at the area of the present-day "Watergate" complex). Present-day Constitution Avenue is built atop the remnants of the old Washington Canal, which was filled in, in the early 1870s, as a health and sanitation hazard. See: Richard Longstreth, ed. The Mall in Washington, 1791–1991, 2nd edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003); Kenneth Hafertepe, America's Castle: The Evolution of the Smithsonian Building and its Institution, 1840–1878 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984); Cynthia Field, Richard Stamm, and Heather Ewing, The Castle: An Illustrated History of the Smithsonian Building, 2nd edition (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2012). |

| 15. | Smithsonian Institution Day Book, 1846–1856, p. 578. |

| 16. | It appears possible to reconstruct the names of these enslaved men. The slaveowner William Clark died July 7, 1855. In 1862, his widow petitioned for compensation for a group of slaves that had been freed by the act of Congress. These included three adult men, whose ages roughly match with those of the unnamed male slaves enumerated in the 1850 slave schedule for the William Clark household: Benjamin Marler, age seventy; William Butler, thirty-two; Frank Joyce, thirty. It seems quite possible that one or more of these men, as slaves, hauled the trees to the Smithsonian grounds. At least two of these men continued to live in Washington: Eight years later, in the 1870 census, William Butler, age forty, is listed as a brick maker, living near seventh street. Residing in the same neighborhood is Frank Joyce, "expressman," age thirty-eight. In the mid-nineteenth century, an "expressman" referred to a wagon driver; speculatively, perhaps Frank Joyce was the "driver" referred to in the Day Book's entry for February 16, 1850. |

| 17. | The controversy over the Washington Lecture Series is detailed in Michael F. Conlin, "The Smithsonian Abolition Lecture Controversy: The Clash of Antislavery Politics with American Science in Wartime Washington," Civil War History 48, no. 4 (December 2000), 301–323. Secretary Henry, a firm believer in scientific racism, argued for the natural inferiority of persons of African descent. A close friend of Senator John C. Calhoun (no friend of the Smithsonian), Henry maintained that blacks could only co-exist with whites in the United States if maintained in a state of slavery. During the Civil War, Henry attempted to maintain the Smithsonian's neutrality in the conflict, refusing to authorize the flying of the Stars and Stripes over the Castle building. He was suspected in some Union quarters of pro-confederate sympathies; he did, however, serve as a trusted scientific and technical advisor to Lincoln on military matters throughout the War. Henry's second in command and successor at the Smithsonian, Spencer Baird, was a noted anti-racist and served as an important advocate for African American Smithsonian employees during his tenure as Secretary (1878–1887). |