Overview

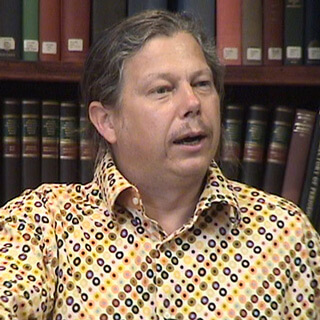

This roundtable discussion, moderated by Dr. Michael Elliott, brings together several prominent scholars of Native American Studies and Native American literature (from left to right: Arnold Krupat, Lisa Brooks, Elvira Pulitano, Craig Womack) to discuss issues of cosmopolitanism, nationalism, translation, and hybridity.

Introduction: Theorists in Dialogue about Native American Literature, Hybridity, and Tribal Sovereignty

Craig Womack: Each of the participants who joined me in the Emory discussion on April 22, 2011—Lisa Brooks, Michael Elliot, Arnold Krupat, and Elvira Pulitano—has authored a range of writings that we might view as creating a dialogue with each other in the field of Native American literature. By meeting together we hoped to increase opportunities for understanding each other’s perspectives, even envisioning a larger conversation that might ensue among interested scholars.

|

Arnold Krupat, the author or editor of ten books on Native literature, dealt with issues of nationalism as early as 1989 in The Voice in the Margin: Native American Literature and the Canon. Without many other resources to rely on that placed Native American literature in a political and legal context, he provided an impetus for later critics to respond to definitions he provided, for example, in a chapter titled “Local, National, Cosmopolitan Literature.” In recent works such as Red Matters: Native American Studies (2002) and All That Remains: Varieties of Indigenous Expression (2009), Krupat expands those preliminary accounts, making the case that in order to effectively resist colonialism, scholars must not define cosmopolitan, national, and indigenous approaches antithetically. In All That Remains, and recent work on Native elegy, he has offered suggestions about ways some of his own cosmopolitan readings have included nationalist understandings. For three decades he has passionately advocated on behalf of Native American literature’s inclusion in the American literary canon and actively supported Native scholars, arguing that no one can have a competent understanding of the history, or literatures, of the Americas, without a substantial consideration of Native peoples.

|

Elvira Pulitano is the author of Toward a Native American Critical Theory (2003), Transatlantic Voices: Interpretations of Native North American Literatures (2009), and a third book on the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Her first book argues that Native literary works are either implicitly theoretical or deal directly with theory.

One of Pulitano’s important contributions to our field in Toward a Native American Critical Theory is that she avoids simply affirming the greatness of all the tribal writers who she focuses on. Scholars have often treated Native writers as sacred cows with the inside scoop on all things Indian, an essentialist notion that Pulitano strongly interrogates, especially in her early chapters. Pulitano argues that certain writers more effectively subvert western authority by fusing Native and western traditions, forcing readers to reconsider Eurocentric hegemony. In contradistinction to this group, she analyzes Native authors who have embraced forms of tribalism which, she argues, ignore the realities of the interdependencies of centuries of colonial contact. Pulitano’s claims, built on a wealth of analysis of postcolonial scholarship, certainly gave me opportunities to reflect on the effectiveness of my own writing.

Robert Warrior, Jace Weaver, and I responded to Pulitano’s book in part but also wanted to honor an essay that had influenced the entire field of Native American literary studies, Simon Ortiz’s seminal 1981 work, “Towards a National Indian Literature.” In American Indian Literary Nationalism (2006), we discuss the Ortiz essay in the Preface and reprint it in the Appendix. As is often the case with great, evocative work, I have seen both hybridists and separatists, and all points in between and beyond, claim that the Ortiz essay proves their point and disproves those they disagree with. For me, it is an essay in which Ortiz prioritizes artful storytelling as a way of explaining how a literature written in English can remain profoundly Indian.

|

In a beautiful Afterword that complements Ortiz’s theory-laden stories in his national literature essay, Lisa Brooks creates a narrative about her community’s fishing rights activism on Vermont's Missiquoi River, working between personal accounts and the language of the court, particularly its emphasis on what one judge called “the weight of history.” Brooks’s stories about language choices provide the basis for her idea that nation language might still appeal to tribal people even at a time when nationalism may be viewed warily.

Lisa Brooks is also the author of The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast (2008), a work that traces historical connections between New England Native intellectuals in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, arguing that we should understand their efforts in concert, not as isolated acts of individual scholarship.

In closing I will mention some questions we could take up in order to continue the dialogue:

If all indigenous expression is mediated by colonial contact, as must surely be the case, is it all mediated in the same way and to the same degree? The issue before us is this: what is the nature of our homework, our next assignment? How can we go beyond theoretical abstraction into specific contexts that explain the meaning of this mediation which, after all, is not universal but of great variation?

|

For me, getting together with Elvira, Arnold, Lisa, and Michael is part of a spiritual journey. I began to realize that my own language has sometimes been problematic, especially for someone who claims an interest in waging peace in our world. As debates go, I felt like I had done fairly well for myself by making some arguments in American Indian Literary Nationalism concerning why tribal viewpoints, even if hybrid, could still be claimed as tribal and as national. The problem with debates, however, is they do very little in terms of community building, a case that is especially evident if one watches presidential debates. Both the Republicans and Democrats will claim their guy won, often based on competing interpretations of the same “facts.” Red on Red and American Indian Literary Nationalism, books I had written with great passion, at some point, began to haunt me. Passion, yes, but compassion? I wasn’t as sure. I had made arguments, maybe even convincing ones. But had I learned anything about listening? Had I sometimes closed down communication instead of opening it up?

As for this conversation at Emory, Pulitano, Krupat, and Brooks deserve special thanks for their courage since, after writing works they might not have anticipated would create controversy, they were not only willing but enthusiastic about sitting down together and working through ideas.

|

Michael Elliott is the author (most recently) of the fine study, Custerology: The Enduring Legacy of the Indian Wars and George Armstrong Custer (2007) that details the way the Custer battle site, and the wider cultural phenomenon of interest in the nineteenth century General, are memorialized from groups as diverse as the National Park Service and Custer re-enactors. Besides being chock full of insightful analysis, it is a rollicking good tale. Michael is also a dean of arts and sciences at Emory, and he did a good job of taking our script for the meeting and turning it into a thought-provoking conversation. PhD students Maud Alamachere, Levin Arnsperger, Dustin Gray, and Ieva Larchey prepared the questions that accompany the video excerpts. Maud, Levin, and Ieva, and their fellow grad student Guirdex Masse, also gave presentations on a morning panel where they spoke about how issues of cosmopolitanism and nationalism affect their own areas of research. Maud spoke about the canonical implications of translating African American dialogue in general, and the writer Toni Cade Bambara in particular, into French. Ieva described oral interviews she undertook with Lithuanian immigrants in Atlanta regarding their hopes for a culture and language after-school program they have founded in the city for their children. Guirdex analyzed the first gathering of the International Meeting of Black Artists and Writers at the Sorbonne in 1956, highlighting some of the tensions between politics and aesthetics among its participants.

Which parts of this debate matter? If one side argues for an open-ended, inclusive nationalism, can we distinguish such a stance from cosmopolitanism, or is the difference merely semantic? What arguments might be served by continuing to insist on our differences? When does the conversation become so esoteric that it no longer provides us the language we can use in our class rooms and home communities? My hope is that we can face these questions together.

Panel Discussion

Part 2: Craig Womack addresses court cases, governmental politics, and historical works

Part 3: Craig Womack and Lisa Brooks discuss the law and legal categories in how Native nationhood is conceived and practiced

Part 4: Lisa Brooks, Arnold Krupat, Craig Womack, & Lisa Pulitano discuss the limits of “literary nationalism.”

Part 5: Arnold Krupat notes how translation affects understandings of cosmopolitanism and nationalism

Part 6: Lisa Brooks and others continue the discussion of translation

Part 7: The panelists discuss the constructedness of critical terms and the usefulness of “hybridity.”

Conclusion and Future Conversations

In this section, the panelists reflect on their discussion at Emory and suggest avenues for future conversations.

Michael Elliott: In the 1990s, while I was in graduate school, the MLA sessions on Native American literature were intense intellectual exchanges—full of creative, passionate thinking about everything from the abstract questions of methodology and canon formation to the concrete ones of syllabus construction. What was exciting was the sense that everyone who was willing to read widely, listen carefully, and contribute generously would be part of building a critical community. The exchange that takes place in this panel continues those conversations—conversations that are also continuing not only at MLA, but also the annual conferences Native American and Indigenous Studies Association and the pages of Studies in American Indian Literature. At stake in these conversations is the purpose of reading Native American literature itself—the question of how literary expression relates to the tangled histories of colonialism, sovereignty, and community. For those of us who are privileged to be members of the academy, we must wrestle with what it means to teach this body of expression in the context of contemporary higher education. Now, in 2011, such inquiry has a particular urgency given the precarious state of literary studies in the academy, and it is no accident that we finally turned to that subject at the end of the conversation. While there are a variety of terms we employ, dissect, and sometimes debate, we all share a commitment to an endeavor that we hope will remain a part of the academic enterprise for generations to come.

Arnold Krupat: Of the many valuable things that came out of our panel, I’d single out the opportunity provided for clarification. I got the chance to explain further my sense that critical perspectives such as nationalism, indigenism, and cosmopolitanism are complementary and overlapping, not oppositional or mutually exclusive. I noted that a good deal of my current work is largely nationalist in perspective—a nationalism that seems to me entirely consistent with my earlier cosmopolitan and ethnocritical perspectives. Further, I explained how and why I had not, in my own critical work (e.g., in Red Matters), used—as Elvira had—the categories hybrid/hybridity to describe either contemporary Native identities or contemporary Native critical perspectives. My preference in these regards has been to speak of “the changing same,” a phrase that resonates well with Gerald Vizenor’s instantiations of continuance and survivance. Finally, to state the obvious, I gained a clearer sense of the other panelists’ positions, something for which I am grateful.

Lisa Brooks: I found it invigorating and illuminating to engage in conversation, over meals and in the classroom, with people whose writing I had passionately disagreed with. I found that we were able to find common ground and to challenge each other, and that we had actually been instrumental to each other’s learning. One of the most important insights I came to during the discussions, which I communicated to the graduate students, was that my own thinking and writing had developed rapidly in response to writings that Arnold and Elvira had produced. As much as Craig’s writing (in Red on Red) had inspired me, Arnold’s early scholarship on Christian Indian writers in New England and Elvira’s later work on Native literary criticism had fueled my own desire to write about those subjects. Because I believed they had missed very critical insights and contexts, I was all the more impassioned with the drive to explore, unpack and explain them. It had never occurred to me what a huge influence this was on my own work, and as I discovered, it turned out that we had all learned a great deal through our engagement with each other’s writing. I have to say that I really enjoyed our time together, more than I imagined. For me, it further solidified my own belief in the importance of gathering together, over food, in private and public spaces, to have those very real conversations. But it also showed me that sometimes the stuff that makes you the most angry is the stuff that fuels your strongest work.

Elvira Pulitano: Upon receiving the invitation to attend the gathering at Emory, I knew that this was going to be a wonderful opportunity for honest academic conversation. As I said to Craig in my initial response, I have always considered intellectual discourse a form of democracy, a forum in which people who might disagree with each other can still learn from the experience. What clearly transpired from this panel discussion was the attempt that all of us made at clarifying concepts that have created so much controversy in the past and, more important perhaps, to think about how we can apply some of these concepts in newly changed contexts.

The panel gave me the opportunity to contextualize my current project on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP or the Declaration) within my previously published work at the same time as it offered all of us additional insights on how questions of nationalism and cosmopolitanism play out in current debates on indigenous rights. The subject of the UNDRIP is a significant departure from my previous work on Native American literature and theory and it might as well reflect my teaching in an ethnic studies department and the kind of interdisciplinary work that goes with it. Yet, what fascinates me about this project and the Declaration per se is the question of whether or not international law, as illustrated by this landmark document, is an instrument that indigenous peoples can use for their emancipation, and, more significantly, whether or not the quintessential Eurocentric nature of international law can be changed upon considering indigenous worldviews and perspectives. In that I see interesting convergences with the theoretical orientation of my previous books. At the same time I was very adamant in editing a collection on the UNDRIP to include literary perspectives—namely, essays that discuss Native writers’ response to some of the provisions set out in the Declaration. Gordon Henry, Jr., Thomas King and Gerald Vizenor among others have written with unrelenting humor about questions of repatriation of remains, museum collections, and ownership (the subject of Articles 11 and 12 of the Declaration), always upholding the centrality of stories to affirm Native histories and identities. Whereas Western legal discourse does not accept stories as valid forms of testimony, Vizenor, in “Genocide Tribunals” (2009) forcefully reminds us that stories have allowed individuals such as Charles Aubid during a dispute with the federal government over of the regulation of wild rice in Minnesota to affirm “his anishinaabe human rights and sovereignty” (131).1Gerald Vizenor, “Genocide Tribunals” in Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009, 131-158.

In terms of our discussion of concepts such as nationalism, cosmopolitanism, and translation, it was illuminating for me to reflect upon how we all agreed that these terms are not necessarily oppositional, but complement each other in interesting, complex ways. Lessons from Frantz Fanon, the advocate of national consciousness and national liberation come to mind. Fanon concludes his seminal study Peau noire, masques blancs with a passionate appeal for a (transnational) humanism, thus paving the way for some of the debates that in subsequent decades would shape the changing nature of the definition of nationalism. We might have not reached the same kind of conclusion over the term hybridity, but Arnold’s point about self-determination or more precisely the sense of feeling “more at home” with specific terms was useful in coming to an understanding of the way in which our use of language is inevitably determined by our cultural experiences. I am not fully convinced that we cannot take a term so vested with negative connotations and transform it into something positive. A few examples from past experiences have clearly shown otherwise: the French nègre as used by the Négritude movement; mixedblood as celebrated by Leslie Marmon Silko in Ceremony; and of course indian as re-imagined by Gerald Vizenor in his postindian interventions. I agree with Craig that this was an important conversation for us to have and that we should all continue to reflect on it next time we address some of these issues in print.

In closing I would like to offer a point of reflection on the idea of bridging cultures and creating dialogue. This gathering would have not been possible without the contributions of the students who attended Craig’s graduate seminar on nationalism and cosmopolitanism. I could not help thinking that the majority of the students in that seminar were from Europe. In reading and reflecting about their questions, I re-lived my experience as a graduate student at the University of New Mexico in the mid-1990s when, by taking courses in Native American literature, I was trying to understand what I could learn from these texts in terms of cross-cultural communication. A generation later, in a post 9/11 America, European students continue to engage Native American literary texts and theories in the attempt to make sense of the world that has shaped them and that they in turn will contribute to re-shape, translating and mediating along the way. The Europe that these students come from has become undoubtedly more complex than the Europe I left when I first came to the United States as a Fulbright scholar from Italy. It has also become more xenophobic and, to put it bluntly, more racist. Yet, as Leslie Marmon Silko reminds us, we must continue to find meaning in “the boundless capacity of language” if we indeed want to bridge those distances between cultures that have kept us apart for way too long. Thank you all for being part of such engaging conversations.

Craig Womack: Criticism and theory, to my way of thinking, should do three things: express itself artfully, illuminate texts, and address conditions in the material world. These three objectives, often in tension, exist on a continuum rather than a set of prescribed rules about what criticism should do. When they come together—for example, Lisa Brooks' telling of generations of families fishing the Missiquoi River, often gathered in recent times at the kitchen tables of Abenaki community leaders, their livelihood undone by a judge’s phrase, while relating her narratives to theories of language that do and undo the nation—worlds open up for me.

This conversation at Emory, born of the goodwill of its participants, will, I hope, continue to elicit and evoke art, illuminate texts, and seek change in the world by addressing our material circumstances.

In terms of artfulness, I have to profess a fondness, if not passion, for those theoretical works that best combine style and substance. In American Indian literary studies, Greg Sarris’s Keeping Slug Woman Alive: A Holistic Approach to American Indian Texts (1993) is a delight to read because of the way it combines excellent storytelling with fresh theoretical insights that make me think and act differently, particularly in terms of examining my teaching practices. Certain of Gerald Vizenor’s works accomplish similar feats of leading me toward new vistas of thought, particularly Interior Landscapes: Autobiographical Myths and Metaphors (1990). In the strictest sense more a work of autobiography, Interior Landscapes, nonetheless, remains an exciting critical study because it involves hard analytical work at the highest levels of creativity. Our job as critics, I believe, is to do whatever we can to facilitate works of such extraordinary caliber and to move people beyond statements that repeat, rather dutifully, platitudes about Native tradition. We should hold true to our calling that we ought to be different than the rest of academe, (and, at times, different than the rest of the tribal world), creating hope that deviant, rather than affirmational, work is always a possibility. As far as our conversation at Emory goes, I think we need to follow up with a discussion of how we might foster this kind of creative criticism. Heavily narrativised literary studies, the kind I have confessed loving, may be only one form of excellence. What other possibilities might exist that could reach the levels of some of these earlier excellent beginnings?

In terms of illumination, I would love to know more about the ways Elvira’s work on her new collection of essays on the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples relates to her earlier work in Toward a Native American Critical Theory. Such analysis could foster discussions regarding what is literary about the UN Declaration as well as what is international (or lacking in international perspective) about US Native fiction and criticism. I would like to continue our discussion of the cosmopolitan citizen of the world since I share Lisa Brooks’s concerns about whether we can rely on this person to concern him or herself with the rights of tribes, a point she raises in our exchange. Which leaders with an international orientation have demonstrated such concerns and how might cosmopolitans and nationalists emulate them?

We address, pretty directly, the subject of hybridity. A central issue we broach is whether or not we need to adapt our understanding of the word or reject it in Native Studies. Some might wonder why, if we had a correct understanding of hybridity's emancipatory potential, we would reject it? Or, similarly, scholars might ask this: if we can get people to understand its power, why not educate them about the meaning of hybridity, the ways it can indicate transculturation rather than assimilation? I find our discussion illuminating because it occurs face to face rather than in print, conveying the immediacy of our concerns about hybridity, and does so in a different way than we had discussed in writing. I am hopeful that the next time we write about this subject we will take into consideration this exchange.

As for examining the material world and creating change, will talking about hybridity affect any aspect of the worlds we live in? If so, let us identify this kind of hybridity talk and start talking it. If not, let’s talk about something else. I see more work at hand in terms of identifying what types of hybridity might have some applicability. I’m in favor of calling it whatever might best facilitate moving hybridity toward action.

About the Participants

Lisa Brooks is an assistant professor of history and literature and of folklore and mythology at Harvard University. She is the author of The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast.

Michael Elliott is the Winship Distinguished Professor of English at Emory University. He is the author of Custerology: The Enduring Legacy of the Indian Wars and George Armstrong Custer.

Arnold Krupat is a Professor of global studies and literature at Sarah Lawrence College. He is currently serving as the editor for Native American materials for the Norton Anthology of American Literature and has recently completed a monograph entitled "That the People Might Live:" A Theory of Native American Elegy.

Elvira Pulitano is an associate professor of ethnic studies at California Polytechnic State University. She is the author of Toward a Native American Critical Theory.

Craig Womack is an associate professor of English at Emory University. He is the author of Red on Red: Native American Literary Separatism.

Recommended Resources

Acoose, Janice, Lisa Brooks, Tol Foster, LeAnne Howe, Daniel Heath Justice, Phil Carroll Morgan, Kimberly Roppolo, Cherl Suzack, Christopher B. Teuton, Sean Teuton, Robert Warrior, and Craig S. Womack. Reasoning Together: The Native Critics Collective. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Brooks, Lisa. The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Elliott, Michael. Custerology: The Enduring Legacy of the Indian Wars and George Armstrong Custer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Krupat, Arnold. The Turn to the Native: Studies in Criticism and Culture. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1976.

———. For Those Who Come After: A Study of Native American Autobiography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

———. The Voice in the Margin: Native American Literature and the Canon. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

———. Ethnocriticism: Ethnography, History, Literature. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

———. Red Matters: Native American Studies. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

———. All That Remains: Varieties of Indigenous Expression. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Pulitano, Elvira. Toward a Native American Critical Theory. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

———. ed. Transatlantic Voices: Interpretations of Native North American Literatures. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

———. ed. "We the peoples": Indigenous Rights in the Age of the UN Declaration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming 2012.

Sarris, Greg. Keeping the Slug Woman Alive: A Holistic Approach to American Indian Texts. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Interior Landscapes: Autobiographical Myths and Metaphors. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

Warrior, Robert. Tribal Secrets: Recovering American Indian Intellectual Traditions. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Weaver, Jace, Craig Womack, Robert Warrior, and Simon Ortiz. American Indian Literary Nationalism. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Womack, Craig. Red on Red: Native American Literary Separatism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

———. Drowning in Fire. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 2001.

———. Art as Performance, Story as Criticism: Reflections on Native Literary Aesthetics. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.

Links

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Gerald Vizenor, “Genocide Tribunals” in Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009, 131-158. |

|---|