Overview

|

| Crystal Bowne, Back-to-the-Land Ozarker Gardens, Newton County, Arkansas, 2010. |

Taking form in cultivated fields and gardens, managed hedgerows and woodlands, varieties of crop species, and livestock breeds, agricultural biodiversity refers to the human-modified components of the natural world that contribute to the sustenance of human populations. Traditional subsistence systems frequently rely on multiple levels of agricultural biodiversity to ensure sufficient food. Such agrobiodiverse subsistence strategies occur most often in marginal landscapes, where large-scale intensive agriculture systems cannot succeed. The Ozark Highlands’ karst topography precludes most forms of intensive industrial agriculture. While the region has advanced technologically, the Ozarks remain a haven for agrobiodiverse farmers and gardeners. Five years of applied agricultural anthropology research in different locales of the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks reveals three clearly interconnected characteristics integral to traditional subsistence in the region: agroecological knowledge, diversity, and frugality. These values allowed Ozarkers of historical times to survive, and they permit contemporary hill dwellers an alternative to the industrial food system. Highlighting the practices of Willodean Smyth, a traditional Ozark farmer/gardener, this essay uses archival and ethnographic research to discuss the interrelationships between agricultural biodiversity and subsistence patterns in the past and present.

Introduction

This here tale begins in the summer of that year, whatever year it was . . . The year don't matter. The national situation don't even matter, because even though we were smack dab in the middle of what we’ve been told was the Depression, folks in the Ozarks was so poor to begin with that they scarcely noticed. No, that's not right, because poverty’s so relative. A better way to put it is that folks in the Ozarks still had everything they needed to subsist and endure, and they didn't want for nothing. So they didn’t even know that people elsewhere all over the country was suffering from want."

—Donald Harington’s “Vance Randolph” character in Butterfly Weed1Donald Harington, Butterfly Weed (New Milford, CT: The Toby Press, 1996), 5.

After supper Uncle Greene . . . began speaking of the Ozarks. ‘Used to be a real happy land for us outlaws,’ he recalled. ‘But for us reformed sons of bitches no country ain’t no great sight better than no other country . . . But I still say . . . that whichever the country, hit’s the backhills that stay interestin’ and closest to everlastin’ . . .’

—Charles Morrow Wilson in The Bodacious Ozarks2Charles Morrow Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks: True Tales of the Backhills (New York: Hastings House Publishers, 1959), 28.

A former student introduced me to her great-uncle who runs the family hardware store in a small town in the Arkansas Ozarks. The store is the modern-day equivalent of the old-timey gristmill, a place of congregation for anyone with a minute to spare. I began the Arkansas component of a long-term research project in that turn-of-the twentieth century brick building in downtown Marshall. I arrived with tape recorder, notepad, and pen, ready to identify participants for a study of Ozark agricultural biodiversity. One of the many names I scribbled that day was Dean Smyth, short for Willodean. When it came to discussing traditional foodways in the region (and in this essay), Willodean, one of the most charismatic and enthusiastic of my contacts, serves as a guide to the continuity of self-sufficient traditions in the Ozarks.

The research foundation for this essay consists of archival data collected in and about each of the subregions of the Ozark Highlands (see Ozark Relief Map below), in addition to semi-structured interviews and participant observation in the St. Francois Mountains (2002-2004), the Boston Mountains and Salem and Springfield Plateaus (2006 and 2009). This research is a component of an applied anthropology endeavor to document and conserve traditional varieties (heirloom) of crops and the family stories related to them. Students, volunteers, and researchers conduct interviews with people who maintain heirloom seed varieties, document and (hopefully) acquire the seeds, store them (along with the stories) in a seed bank and database, grow them out in campus and gardens, and give them away at Seed Swaps.

|

| Crystal Bowne, Back-to-the-Land Ozarker Gardens, Newton County, Arkansas, 2010 |

The most traditional, conservative Ozark inhabitants, who constitute the cultural focus of this research, have been ethnocentrically misrepresented in both popular and academic media.3Brooks Blevins, Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). Misrepresentations of Ozarkers emerge through a lack of cultural relativism and an inability or unwillingness to comprehend traditional Ozark culture. The cultural anthropology approach, with its methods of participant observation and semi-structured interviews, allows the researcher to move beyond stereotypes and gain an understanding of the interconnections between the motivations, perceptions, and practices of a group of people.4Karl G. Heider, Seeing Anthropology: Cultural Anthropology through Film, 4th ed. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2006). Robert H. Lavenda and Emily A. Shultz, Core Concepts in Cultural Anthropology, 3rd ed. (Boston: McGraw Hill Companies, Inc., 2007).

This study presents Ozark seed savers and agrobiodiverse farmer-gardeners at the beginning of the twenty-first century, but it expands beyond conventional ethnography in two ways. I do not focus strictly on the present; instead I engage past subsistence traditions to elucidate contemporary practices, and I cast a wider net, utilizing a more diverse range of media to illustrate the Ozarks as a refuge for agricultural biodiversity. Drawing upon historical and contemporary photographs, recipes, folk tales, works of ethnographic/historical and autobiographical fiction, as well as excerpts from interviews with Willodean and other Ozarkers, these sources illustrate the diversity, agroecological knowledge, and frugality inherent in the region’s subsistence traditions.

Agricultural Biodiversity

With its adoption of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro highlighted the implications of species extinction and imprinted biodiversity upon the public consciousness as a buzzword for species richness and global health.5Hope Shand, Human Nature: Agricultural Biodiversity and Farm-Based Food Security (Ottawa: RAFI, 1997). While biodiversity became synonymous with the importance of not cutting down the rainforest, environmental anthropologists have attempted to expand that narrow conception. Most of the “natural,” pristine, or “virgin” landscapes that early European explorers encountered in the Americas were actually anthropogenic, created through human modification and management.6Bill Balee and Darrell Posey, Resource Management in Amazonia: Indigenous and Folk Strategies (New York Botanic Garden series, Advances in Economic Botany, 1989). Nancy J. Turner, The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005). Unlike the common perception of humans as the cause of biodiversity loss, humans have enhanced or created biodiversity in their ecosystems through traditional management systems.7 Gary Paul Nabhan, Cultures of Habitat: On Nature, Culture, and Story (Washington DC: Counterpoint, 1997). Virginia Nazarea, Cultural Memory and Biodiversity (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1998). M.L. Oldfield and J.B. Alcorn, "Conservation of Traditional Agroecosystems," Bioscience, 37 (1997) 199-208. E. Smith and M. Wishnie, "Conservation and Subsistence in Small-scale Societies," Annual Review of Anthropology 29 (2000): 493–524. Nancy J. Turner, The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005).

Agricultural biodiversity refers to human-modified components of biodiversity that contribute to the sustenance and health of human populations.8Shand, Human Nature. This includes the domesticated plants and animals that constitute the foundation of agriculture and the non-domesticated plants, shrubs, and trees utilized for subsistence and health and the related soil biota and insects necessary for plant propagation and reproduction.9T. Johns, I.F. Smith, P. Eyzaguirre, "Understanding the Links Between Agriculture and Health" IFPRI, 13 (2006), 12-16. Several approaches characterize agrobiodiverse farming systems: 1) polyculture; farmers grow an assortment of crop species within a field or agricultural landscape; 2) intraspecific diversity; more than one variety of a species exists in the fields; 3) wild-domesticated continuum; farmers allow non- and semi- domesticated species to grow within and around fields; and 4) utility diversity; species in the fields have multiple uses, as livestock feed and human food, medicine, dye, clothing, storage, cordage, etc.10M.A. Altieri, Agroecology: The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture (Boulder: Westview Press, 1995). Shand, Human Nature. Farmers the world over engaged in such practices before the now ubiquitous modern industrial agricultural model replaced diversity and self-sufficiency with specialization.11Altieri, Agroecology. T. Smith and Eyzaguirre, 2006. Eugene Odum, Ecology: A Bridge Between Science and Society (Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 1997). When the farmer focuses strictly on large-scale production of one crop for the market, the animals that previously produced manure for fertilizer, in addition to their meat, eggs, milk, or labor, must now be replaced with tractors, chemical fertilizers, and store-bought food. If the farmer moves to large-scale animal production, s/he must purchase large amounts of feed and abandon diversified production of crops. Instead of using manure as fertilizer, it becomes a point-source pollutant, requiring extensive mitigation measures to prevent groundwater pollution. Either way, a loss of self-sufficiency results.

While much agricultural biodiversity research has focused on farms and full-time farmers, studies reveal the comparatively high diversity of species and varieties in home gardens.12Virginia Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005). J.W. Watson and P.B. Eyzaguirre, editors, "Proceedings of the Second International Home Gardens Workshop: Contribution of home gardens to in situ conservation of plant genetic resources in farming systems," 17–19 July 2001, Witzenhausen, Federal Republic of Germany. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, 2002. This new angle makes sense in light of the widespread shift from traditional to industrial agriculture throughout the world, transforming home gardens into refuges for culturally important crop species and varieties.13Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers. Agricultural biodiversity researchers have encouraged an investigative approach emphasizing persistence in traditional farming practices within or despite culture change.14B. Orlove and S. Brush, "Anthropology and the conservation of biodiversity," Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996), 329-352. In Heirloom Seeds and their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity, Virginia Nazarea explores “seedsaver gardens as repositories of ambiguities and alternatives that can effectively counteract homogenization and avert cultural and genetic erosion.”15Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers, 16. She encourages researchers to “shift from conceptual, aggregate units such as “organizations” and “populations” (whether local or not) to actual people – people who acquire and pass on knowledge collectively and individually.”16Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers, 19. This essay follows these leads by focusing on the diversity of one particular farmer/gardener to gain insight into traditional agrobiodiverse farming and gardening practices in the Ozarks.

The Biophysical Geography of the Ozark Highlands

The Ozark Highlands region comprises the southern half of Missouri, northern third of Arkansas, and a small fraction of northeastern Oklahoma, which geographers generally delimit by rivers: the Missouri on the north, the Mississippi on the east, the Grand on the southwest. Geographic characteristics that distinguish the Ozarks as a region include the general ruggedness and vertical topography, and the relative age of surface rocks being older than those in adjoining areas.17Milton Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001). The karst topography of the Ozarks creates many of these geographic characteristics; the soluble rock (dolomite and limestone) dissolves as groundwater filters through it. Much of the precipitation in karst areas carries nutrients critical to plant growth directly into the groundwater, well below rooting depths of most agricultural plants.18Tom Aley, "Karst Topography and Rural Poverty," Ozarkswatch 5.3 (1992), 19-21. Land cover in the Ozarks relates directly to these effects of the karst topography; unlike the surrounding regions, large-scale monoculture agriculture is untenable in the Ozark hills. Deciduous forests of oak-hickory-pine mixes with intermittent cedar glades compose the Ozarks’ primary landscape feature.

|

| Ozark Relief Map, 2007 |

People from in and around the region refer to the Ozarks in a variety of ways, as the Ozark mountains, hills, highlands, plateau, escarpment, and to residents as Ozarkers, Ozarkians, hillbillies, baldknobbers, ridgerunners, hillpeople, in addition to some others not fit to print.19Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Vance Randolph, Pissing in the Snow, and other Folktales (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1976). Before modernization thoroughly infiltrated the Ozarks, even as late as the 1960s, the Ozarks constituted a discrete cultural province, with communities and isolated homesteads of self-reliant forager/gardener/farmers with their unique folkways and dialect scattered throughout.20Brian Campbell, "Ethnoecology of the Ozarks’ Agricultural Encounter," Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology, 48.1(2009), 1-20. John Soloman Otto and Augustus Marion Burns III, "Traditional Agricultural Practices in the Arkansas Highlands," The Journal of American Folklore, 94 (1981), 166-187. Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Vance Randolph, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society (New York: Vanguard Press, 1931). With the construction of roads and bridges in previously remote areas, exposure to mainstream media through television and radio, and the concomitant decline of diversified farming as a livelihood, a significant percentage of the Ozark population abandoned or never learned the agrarian lifeway.21Blevins, Hill Folks. W.O. Cralle, "Social change and isolation in the Ozark Mountain Region of Missouri," The American Journal of Sociology 41 (1936), 435–446. Art Gallaher Jr., Fifteen Years Later (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961). James West, Plainville, U.S.A. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1945).

|

| Arthur Keller, Old Stock garden, Baxter County, Arkansas, early 20th century. Courtesy University of Central Arkansas Archives, Butcher-Keller Collection. |

Despite these relatively sudden and vast changes, the Ozark Highlands has retained many farming and gardening traditions, and constitutes a distinct bio-region. Researchers recognize the region as a contemporary refuge for unique open-pollinated (folk, heirloom, old-timey) varieties of agricultural crops.22Campbell, "Ethnoecology of the Agricultural Encounter in Ethnology." James R. Veteto, "The history and survival of traditional heirloom vegetable varieties in the southern Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina," Agriculture and Human Values 25 (2008), 121–134. K. Whealy, Foreword. In S. Stickland (ed), Heirloom Vegetables: A Home Gardener’s Guide to Finding and Growing Vegetables from the Past (New York: Fireside, 1998). The Ozarkers who engage in agrobiodiverse farming and gardening rarely constitute a “population” or community or discrete cultural unit, but rather are dispersed throughout the region in pockets or “hollers” disconnected from one another. In the rural areas outside of the small Ozark towns, most homes feature a garden that has some mix (depending on the season) of basic staples, such as beans, cabbage, canteloupes, cucumbers, mustard greens, okra, peppers, potatoes, squash, tomatoes, turnip (greens), watermelons, and perhaps some corn. Yet the percentage of those gardens that house open-pollinated varieties rather than hybrids has fallen drastically over the last quarter century; I estimate that less than one quarter of Ozark gardens today can be characterized as “agrobiodiverse,” with at least several open-pollinated crop species in cultivation (not including hybrids and ornamental species). The total percentage of Ozarkers engaged in agrobiodiverse farming and gardening at the beginning of the twenty-first century is likely around ten percent, if not less, and these are spread throughout the region. As Nazarea and Orlove and Brush indicate, this discussion of agricultural biodiversity conservation acknowledges “the complexity of plant populations in dynamic and patchy social contexts.”23Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers. Orlove and Brush, "Anthropology and the conservation of biodiversity," 342. Indeed, the contemporary Ozarks, as much as anywhere else, represents the patchiness and dynamism of agricultural biodiversity.

|

| Zachariah McCannon, Old Stock Ozark garden, Newton County, Arkansas, 2007. |

Ozark Settlement history and Demography

Prior to Euro-American settlement, the Ozarks was sparsely populated. There is archaeological evidence (spearpoints and mastodon and mammoth kill-sites) for Paleo-Indian (12000-8000 BC) and Archaic (8000-1000 BC) period occupation of the region. During the Woodland (1000 BC – AD 900) and Mississippian (AD 900-1700) periods the region housed forager-gardeners similar to the pre-modern Euro-American Ozarkers, with the main difference being the agricultural species grown. Deer and elk provided the bulk of the meat consumed; nuts (acorn, hickory, and walnut) and fruits (elderberry, grape, persimmon, plum) constituted the majority of the plant foods; and now-obsolete domesticated species (amaranth, chenopod, little barley, maygrass, sumpweed, sunflower), squash species and small amounts of corn provided a minimal percentage of the diet.24Gayle Fritz, "Identification of Cultigen Amaranth and Chenopod from Rockshelter Sites in Northwest Arkansas," American Antiquity, Vol. 49 No. 3 (1984), 558-572. George Sabo and Jerry E. Hilliard, "Woodland Period Shell-Tempered Pottery in the Central Arkansas Ozarks," Southeastern Archaeology, Winter 2008. From approximately AD 1500 through 1700 there was very little Native American occupation of the interior Arkansas Ozarks.25Kenneth L. Smith, Buffalo River Handbook (Little Rock, AR: The Ozark Society, 2004). During the historic period, from about 1700 until 1808, when they ceded the lands to the US government, the Osage maintained the Ozarks as a seasonal homeland and hunting reserve. The region also served as a refuge for displaced Native American groups (Cherokee, Choctaw, Delaware, Kickapoo, Shawnee) who came into conflict with the Osage as they attempted to settle.26Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Of these diverse contemporary Native American groups, the Cherokee have established the most lasting and evident imprint on the region. By the late eighteenth and through the mid-nineteenth century, Cherokee splinter groups left the east and settled in the Ozarks.27Timothy Jones, "Commentary on 'Cultural Conservation of Medicinal Plant Use in the Ozarks.'" Human Organization 59(1)(2001), 136-140. During the 1830s, the Indian Removal Act forced southeastern tribes onto the Trail of Tears. En route to Oklahoma many Cherokee escaped into the Ozark hills. Despite forced removal of known Native Americans from the Ozarks to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) beginning in 1820, many Cherokee maintained anonymity and remained in the Ozarks. Some Cherokee intermarried with Euro-American homesteaders or clandestinely remained with groups of fellow Cherokee, which was not all too difficult because many they had already adopted the general subsistence and architectural strategies of their Euro-American neighbors in the Southeast.

The first Europeans in the Ozarks were French creoles, who almost exclusively exploited the mineral resources and fur-bearing animals. They established settlements on the fringes of the Ozarks, in what is now southeastern Missouri. Spain took formal possession of the region in 1770 and readily distributed land-grants to Americans to protect the territory from the British. France similarly used “Louisiana” strategically, and after re-establishing control of the region, sold it to the United States in 1803. Subsequently, Ozark lands were given to veterans of the American Revolution and the War of 1812 as payment for their military service. Ozark homesteaders of the nineteenth century were predominantly Scots-Irish, accustomed to living on the frontier, in close contact with Native American enemies and allies.28Blevins, Hill Folks. Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Typically young men would precede their families and begin the homesteading process, later sending word for the rest of the family to join them. In their relative isolation, they frequently became involved with local women, often of Native American (Cherokee, Choctaw, Quapaw, Shawnee) heritage. Native Americans contributed significantly to contemporary agricultural biodiversity because early homesteaders learned how to harvest and utilize wild species from Cherokee and other Native American residents and also integrated some of their domesticated species into their gastronomy. African-Americans, on the other hand, constituted a small proportion of the Ozark population in the past and present. Early settlers were mostly poor, landless, and without slaves. A few slaveholders settled in the fringe river valleys. During the Civil War and the decade after, many African Americans fled because of the lawlessness and violence.

|

| Arthur Keller, Display of pumpkin harvest, Mountain Home, Baxter County, Arkansas, early twentieth century. Keller-Butcher Collection, University of Central Arkansas Archives. |

Descendants of the earliest Ozark homesteaders who continue to reside in the region, such as Willodean, are referred to as Old Stock Ozarkers to differentiate them from more recent in-migrants.29Russel L. Gerlach, Immigrants in the Ozarks : A Study in Ethnic Geography (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1976). While some Old Stock residents in the twenty-first century continue to engage in seed saving and agrobiodiverse gardening traditions, most have adopted technological conveniences and abandoned traditional practices. More recent Ozark settlers have arrived with specific intentions of perpetuating traditional agrobiodiverse farming practices. Beginning with Depression era “back-to-the-landers” of the Arts and Crafts and Country Life movements through the counter-culture of the 1960’s and ‘70s, people raised in urban environments have sought the Ozarks as a pastoral getaway to experiment with, and sometimes persevere in rural living.30Blevins, Hill Folks, Campbell n.d.

The Ozarks has consistently served as a destination for disillusioned Arcadia-seekers because of the inexpensive land, isolation, beauty and abundance of water. Most of these back-to-the-landers have been “driven back to civilization by snakes, chiggers, heat, cold, and starvation,” but many have also remained.31Blevins, Hill Folks, 200. While exact numbers are impossible to ascertain because there is no census category for this variable and these homesteaders are by choice difficult to document because of their avoidance of mainstream societal institutions, they represent a small percentage (five to ten) of the population in most Ozarks counties, but in some, such as Newton and Stone counties in Arkansas and Ozark County in Missouri, the percentages are much higher. Donald Harington characterizes such back-to-the-land Ozarkers as similar to earlier homesteaders:

Elsewhere in Arkansas the latest blooming hippies have all cleaned up and moved back to the suburbs. Those who persist and endure in Newton County, are the strong ones, fit survivors, like the real pioneers in the nineteenth century, who came as a kind of spillover of the mountain settlement to the east.32Harington, Let Us Build Us a City: Eleven Lost Towns. (New Milford, CT: The Toby Press, 1986), 98-9.

|

| Arthur Keller, Man standing among tomato plants, early 20th century, Mountain Home, Baxter County, Arkansas, Keller-Butcher Collection, University of Central Arkansas Archives. |

Harington’s romanticized portrayal in this semi-autobiographical work captures the back-to-the-land subset relevant to this research; however it omits the poverty and difficulties of many such inexperienced urban refugees.

Back-to-the-land homesteaders may not have the family tradition or childhood experience in the Ozarks, but they usually bring a range of seeds, many of which are new to the region, and books on homesteading, organic gardening, and seed-saving, and eventually develop local networks to assist them in their adaptation to the landscape. They typically share the frugality of Old Stock residents and engage in traditional, long-abandoned practices such as plowing with mules or horses. They rarely realize their aspirations of self-sufficiency. Back-to-the-landers almost always fall back on some form of occupation to supplement their gardening, farming, and/or foraging. As Tina Marie Wilcox, Ozark Folk Center head gardener and back-to-the-lander explains: “I moved to the Ozark Mountains with the mission of growing all of my own food. I’ve learned that this is easier said than done.” Contemporary Old Stock Ozarkers have no such illusions of making a living through farming, rather they tend to heavily supplement another occupation with foraging, farming, gardening, and hunting. Old Stock Ozark families invariably refuse to sell their garden surplus, preferring to give it away to family and neighbors.

General Characteristics

These subsistence strategies supplement Ozarkers wage income, which tends to be comparatively low. For example, Searcy County, Willodean’s home county, has 667 square miles, with twelve people per square mile, which is a very low population density. According to the US Census Bureau, the median household income in 2008 was $25,807, with approximately one quarter of the county population living below the poverty level. The most common jobs for men in Searcy County include construction (20%), agriculture, foraging, and forestry (13%), and woodworking (12%) (timber and furniture and related production); for women they are health care (17%), education (14%), and food services (12%). 96.8% of the population is characterized as “White Non-Hispanic,” followed by “American Indian” (1.8%). Sixty-eight percent of residents over twenty-five years of age hold a high school degree, while only 8.4% have a bachelor’s degree or higher. The Ozarks in general has been described as “overchurched” in reference to the myriad sects, denominations and evangelical fervor.33Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. An overwhelming majority, 92%, of Searcy County residents (who participated in the census) reported their religion as evangelical Protestant, (Baptist 57%, Church of Christ 13%, Assembly of God 10%, and other) while the remaining 8% reported themselves as United Methodist. The residents lean toward the right in their political stance, with between 60 and 75% voting Republican in the presidential elections of 2004 and 2008.

Geography and Gastronomy

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the vast forests of the region attracted the industrial timber industry from outside. Logging companies denuded many of the Ozark hillsides of their virgin white oak forests. The shallow soils, with nothing to hold them in place, washed away, choking streams and rivers. Previously abundant fish and game disappeared as their habitats were destroyed and desperate Ozarkers over-harvested those that remained. Many Ozark homesteaders left, typically heading for California, because they could no longer make a living in the degraded landscape. The US government purchased enormous tracts of this Ozark land for pennies on the dollar and converted it into National Forests.34Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life.

Those families who scraped by in the Ozarks represent the defining sociological character of the region – mirrored by the landscape – ruggedness. They survived because they diversified their subsistence base; they obtained food not only from their own production, but also by their awareness of it in the wild. Charles Morrow Wilson, journalist and chronicler of the Ozarks in the first half of the twentieth century, documented and celebrated the Ozarks as a special place with a uniquely independent population, noting the traditional foodways. Few other primary or secondary sources from this era indulge the reader with ethnographic details about the agricultural biodiversity used in Ozark foodways. A key motivation for his in-depth discussion must be that Wilson had the “Divine permission to grow up on an Ozarks farm in an era when the utilization of the home-grown and home-picked, plucked or otherwise recovered, was in prime.”35 Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 152. As modernity increasingly invaded, Wilson lamented the decline in subsistence traditions:

There is no substitute for experience in the actual growing or gathering, cooking and eating of the foodstuffs. . . . It stays particularly true in the rural Ozarks where many of the most distinguished and delectable dishes were born directly of poverty and isolation. Both of the latter-named phenomena are now on the wane. So is at least some part of the charm of Ozarks cookery. But this is not inevitable. The culinary distinction can be restored and maintained to the extent that people are willing to experiment, to propagate both new and old varieties of edible plants in fields, gardens, orchards and berry beds, and even more definitely to take food materials directly from the open fields, ranges, woods and creeks or rivers.36Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 164-5.

While Wilson worried that these Ozarkian traditions might perish half a century ago, this essay aims to reveal that in terms of agrobiodiverse subsistence his Uncle Green was on track with his opinion “that hit’s the backhills that stay interestin’ and closest to everlastin’.”37Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 28. His assessment resonates with anthropological literature on cultural characteristics of pre-modern mountain regions; they are frequently inhabited by marginal groups with traditions distinct from lowland, mainstream populations.38Robert Rhoades, "Integrating Local Voices and Visions into the Global Mountain Agenda," Mountain Research and Development 20(1)(2000), 4-9. A significant portion of the cultural traditions that distinguish highland populations revolve around subsistence. As long as people seek out the mountains to avoid the mainstream, they subsist by consuming locally adapted species in that landscape. The isolation of the Ozark mountains also allows for a flourishing, clandestine underground economy, which consists of a wide range of economic transactions outside the formal market. These activities range from general barter, undocumented hunting and foraging, and the production and sale of illicit substances such as moonshine, marijuana and methamphetamines.39Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Rural Ozarkers usually adhere to a “live and let live” philosophy; whether they approve of, or engage in such activities or not, they tend to ignore them as long as they do not negatively affect their families directly.

Willodean: Ozark Subsistence Traditions in the Present

|

| Brenda Smyth, Willodean's garden, Searcy County, Arkansas, July 2009. |

On a spring day in 2009 I visited the home of Kenneth and Willodean Smyth in Marshall, Arkansas. They live a mere six blocks off the main highway, but their fifteen acres boasts a very large garden, fruit trees, nut trees, blackberry brambles, chicken coops, a humble, comfortable residence, and a priceless view of the forested Boston Mountains (Ozarks) in the distance. During the interview Willodean toured me around her gardens, planted approximately a month earlier, showed me the coop for her bantam fan-tail chickens, and led me down into the cellar. The cellar contained a woodstove, an enormous freezer stocked with meats and grains, most notably her family variety cornmeals milled down the road, and a 12’ x 12’ room completely full of canned preserves. She proceeded to rattle off the contents of every group of Mason jars, with agronomic and culinary anecdotes accompanying each. This essay uses those anecdotes as springboards for detailed discussions of the three interconnected concepts that emerge in my analysis of traditional Ozark subsistence: diversity, agroecological knowledge, and frugality.40While animals constitute a very significant component of traditional Ozark subsistence, this research focuses exclusively on the diversity of the home garden and cellar (for more on animals in traditional Ozark agroecology see Brian Campbell, "'A gentle work horse would come in right handy': Animals in Ozark Agroecology," Anthrozoös: A multidisciplinary journal of the interactions of people and animals, 22(3) (2009), 239-253).

Willodean Smyth exhibits agroecological knowledge and frugality in the creative strategies she uses to recycle materials to ensure that nothing goes to waste. Diversity is on display by the range of species and varieties grown and used and in the array of methods of preservation and consumption. Prior to the early twentieth century, the only methods of preservation consisted of salting (meats), pickling (various vegetables), drying (fruits and meats) or burying (typically tubers and some squashes) in the ground. Once canning was introduced and caught on, with much urging from Extension agents, Ozark housewives prided themselves on the amount of food they could “put up,” with estimates of “100 to 400 jars (quarts or half-gallon)” being acceptable.41West, Plainville, U.S.A., 37. The unpublished memoirs of Alice Dillard Smith of Marion County, Arkansas, born in 1894, set the bar even higher:

We use to have to raise our living, can and preserve it for winter use. I was always glad when the first frost fell for that meant my canning was about over, which I always did a lot of. One summer we canned 1600 quarts of fruit and vegetables. We didn’t have to worry about something to eat after the canning season was over; we looked forward to Hog Killing time.42Alice Dillard Smith (born 1894), Unpublished, hand-written memoirs. Marion County, Arkansas.

Diversity

|

| Carl Mydans, Drying Jars for Canning Time, Missouri Ozarks, May 1936. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

Diversity exists not only in the range of species grown in a garden or field, but also in the distinct varieties of a species grown annually or from one year to the next. Old Stock Ozarkers who grow an annual garden frequently maintain some of their parents’ open-pollinated seed varieties. Gardening provides them with their own produce, and saving seed closes the loop, conferring independence, a valued trait. While many Old Stock seed savers do not refer to their family seeds as heirlooms, seed saving became so rare in the late twentieth century that mainstream society applied the term to such inter-generationally saved seeds. Old Stock Ozarkers who maintain family varieties do so for various reasons: to preserve their family history, to grow seed that requires minimal inputs to successfully produce on their farms, and especially to have the correct ingredients for the meals they like the most (e.g. bean dishes, cornbread, fried okra, grits, hominy, soups, squash casseroles). They consistently inform me that hybrid varieties just “don’t taste right” in their family recipes. Willodean maintains her open-pollinated varieties because she enjoys the holistic process of gardening, seeing the seed through the entire cycle.

|

| Vaughn Brewer, Claudia Gammill, age 89, Stone County, Arkansas, 1979. Courtesy of University of Central Arkansas Archives, Rackensack Collection. |

Willodean continues an Ozark tradition when she plants a wide array of species in her garden; squash, cucumbers, garlic, onions, lettuces, corn, beans, peas, peppers, potatoes, tomatoes, turnips, and more fill every last inch of her tidy one acre patch. Abundant and diverse garden produce historically provided a significant portion of most Ozarkers’ diets. In 1979, Claudia Gertrude Gammill of Stone County, Arkansas asserted: “I made sixty-eight gardens in the same garden spot out here and I have not missed a year.” Her gardens included:

. . . tomatoes. . . peanuts. . . two or three acres in peas, a sorghum molasses patch, the cane to cut for hay for mules and stock to eat. . . Kraut cabbage. . . Three or four acres or five in cotton and corn. . . Taters, turnips, taters of both kinds and all kinds of garden stuff, onions, cabbage, and everthing beans, beans, planted in the corn, what is called white soup beans, . . . a yellow-pale yellow bean that I raised out just in the rows. There is a bunch bean. All of the beans we could eat all winter long.43Rackensack Collection, unpublished oral histories conducted in Stone County, Missouri in association with Jimmy Driftwood. University of Central Arkansas Archives. Conway, Arkansas.

In 1833, an immigrant to the region noted the seed varieties she transported from Germany to the Missouri Ozarks in cloth bags and paper seed packets:

. . . three kinds of green peas, four kinds of beans, three of carrots, three of onions, three of cabbages, two of beets, plus parsnips, cucumbers, gherkins, spinach, rhubarb, kohlrabi, leeks, and four kinds of turnips, two of which were for animal feed. . . gooseberry, blackberry, raspberry, and strawberry seeds, and for her planned orchard apple, cherry, peach, pear, quince, apricot, and plum seeds. Some twenty years later she wrote, "We have 22 apple trees; 10 cherry; 12 peach; 5 quince; 9 plum; 16 pear; 6 apricot; 16 crab-apple. We started by planting from seeds that I brought with me from home.44Erin McCawley Renn, "German Food: Customs and Traditions in the Missouri Ozarks," Ozarkswatch 3(3) (1990), 14-19.

Corn (Zea Mays), an Ozark Staple

Corn has been a key component of Ozark subsistence, appearing in one way or another at each meal.45William McNeal, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992). The continuity of culinary traditions perpetuates diverse seed saving because family recipes sometimes require (or taste better with) particular varieties of crops such as corn. Because hominy remains a popular food in traditional Ozark homes, those families continue to grow open-pollinated field corn.

|

| Zachariah McCannon, Hominy made with Hickory King corn, Stone County, Arkansas, 2008. |

In Bittersweet Country Ellen Gray Massey explains the practicality of hominy:

Making hominy was a way to continue using corn after the growing season in some form other than corn meal. Since the stored dried corn would not spoil, the ingredients were always at hand and it could be made throughout the year as a vegetable dish. Either yellow or white corn can be used, though most preferred white corn because it makes such a pretty white fluffy product. The variety that most preferred was Hickory King (usually pronounced “cane”).46Ellen Gray Massey, Bittersweet Country (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978), 40.

Ozarkers maintain that neither sweet corn nor hybrid field corn varieties can be used to make hominy appropriately. In 1982, Anna McDowell, of Madison County, Missouri explained:

I can tell you one thing, you can’t make hominy out of this hybrid corn. It’s got to be old fashioned or whatever you call it. I’ve tried it twice since I’ve been here with that hybrid corn, and you just can’t make hominy out of it. Oh, it’ll peel good, but . . . you just can’t cook it done enough. There’s a big difference in it.47Dana Hamilton, My Daddy Taught Me to Doctor Snake Bites! Mozark: Cultural Journalism of Madison County, Missouri High School English Class (Fredericktown Missouri Public Library Collection, 1982), 56.

| Willodean's Hominy with Lye recipe | |

| 6 cups corn 8 or 9 cups of water 1 tbsp lye | |

| Put in stone jar or glass, stir with wooden spoon. Soak overnight in glass or crock container in lye solution. Cook 30 minutes or until eyes come off easy in porcelain or cast iron pot. Stir last 15 minutes constantly. Dip out of kettle and strain. Change water and put corn back in. Boil 20 minutes. Repeat 2 or 3 times or until the water clears up. Fill jars ¾ full and add water and 1 tsp salt to top. Cook 1 hour. 10 lb pressure for 40 minutes. Yield 6 ½ pints. |

|

| Brenda Smyth, Willodean in her garden, Searcy County, Arkansas, July 2009. |

Willodean conveys ecological knowledge about the cross-pollination of various species and how to maintain pure seed varieties. Specifically she indicates that because she has more than one corn variety in her field she must separate them to prevent cross-pollination. Corn is wind-pollinated; once the tassels emerge and produce pollen the wind blows it onto the silks emerging from the developing ears below. Each kernel has a silk that must be dusted with pollen in order to develop. Corn varieties can easily cross, unless separated by a mile or two, or their planting is staggered to ensure that only one variety is spreading pollen at a time.48Suzanne Ashworth, Seed to Seed: Seed Saving and Growing Techniques for Vegetable Gardeners (Decorah IA: Seed Savers Exchange Press, 2002).

In the Ozarks, I have documented both seed-saving farmers who consciously prevent cross-pollination to ensure seed purity and others who do not concern themselves with cross-pollination, allowing the genetics of their seeds to intermingle. In this case, Willodean planted both Tennessee Red Cob, a field corn used to make corn meal, hominy or grits, as well as a sweet corn variety that would be eaten on the cob. Ozark farmer/gardeners frequently plant one field corn and one sweet corn variety each year.49Massey, Bittersweet Country. To reduce the possibility of cross-pollination, Willodean strategically plants other species in between each variety to block the flow of pollen from one corn variety to the other. She also chronologically staggers their plantings. Another way to prevent cross-pollination is to have someone else grow it, as Willodean explains about her daughter:

She got some black corn at the Seed Swap and she didn’t have space [in her garden]. I didn’t want it to cross with my corn in my garden so she had a neighbor up in Harrison grow it. She says: “It’s the strangest lookin’ corn I ever seen. It’s like a bush, with an ear on every stalk.”

The most common field corn (Zea mays) varieties found as heirlooms from the Ozarks include Bloody Butcher, Hickory Cane (King), Old Joe Dent, Pencil Cob, Possum Walk Special, Red Indian, Tennessee Red Cob, in addition to several popcorn varieties, such as Strawberry and Indian. I have documented many additional varieties that families name after a specific person, such as Ted Horton or Alfred Drury corn. Some of these corn varieties can be recognized as variants of historical varieties that were brought into the area from Appalachia (Hickory “Cane” [King], Tennessee Red Cob). The names indicate an Ozarkian (possibly universal) tendency to name a seed variety after the person who introduced it into the family. A comical exchange occurred when the sixty-year-old son of a seed saving matriarch was sent back to the pantry to retrieve some “Grandma Milsap’s” pinto beans and came back with several bags of bean seeds. He poured the contents of a bag out in his hand: “Is this them mama?” She studied the seeds and finally said: “No. That’s them John Dee beans.” Her son and daughter both giggled, having never heard about these beans, and she clarified: “I don’t know where John got them. They’ve been in the family for years. We don’t plant them anymore, because we don’t really grow field corn anymore and you have to have the field corn to vine’em.” She continued with a genealogical overview of John Dee, which reflects the power of seeds to preserve history and root cultural identity.

This exchange also elucidates a distinctive practice in agrobiodiverse farming: interplanting; in this case, John Dee beans are “cornfield” beans because they vine and climb the corn stalks, simultaneously fixing nitrogen for the corn plants. But because the family no longer grows field corn, they have abandoned this related seed variety. This exemplifies agricultural biodiversity loss and the interconnections between species; as particular traditions cease, related components, such as seed varieties disappear also.50S.B. Brush, Genes in the Field, On-Farm Conservation of Crop Diversity (Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers, 2000).

|

| Brian C. Campbell, John Dee cornfield beans, Newton County, Arkansas, 2007. |

|

| Photographer unknown, Avery Brothers’ grandfather’s water-powered gristmill on Big Springs, Stone County, Arkansas, circa 1900. Courtesy of University of Central Arkansas Archives, Rackensack Collection. |

Gristmills were commonplace in rural areas through the mid-twentieth century. They were a place of congregation where people told stories, went on short hunting expeditions, whittled and/or reminisced while their corn was being milled. As early as 1840, there were at least four gristmills for stone grinding corn in each county of the Ozarks.51Blevins, Hill Folks, 22. In the early 1940s, Mr. A. O. Weaver, who “was seen on his mule, with a sack of corn strapped to his saddle, a gun in his hand, and his hound-dogs following along . . . on his way to the old Cedar Grove gristmill, to have his corn ground into meal” remarked:

This ol’ Cedar Grove mill is a real ol’ timer an’ has been grindin’ out corn meal ever since long before the Civil War. It has purtnye [pretty near] raised my family ‘cause there is where I’ve allers [always] took my corn to have it made into meal,. . . We’ve got to have corn meal at our house or we can’t live. I’ve got a big family an’ it takes lots ov bread, an’ when I go to the mill, I allers take my gun an’ dogs along an’ by the time I make the round an’ get back home, I’ve usually got a bunch of squirrels tied to this ol’ white mule, an’ that shore helps a lot at our table ‘cause we all like wild meat, sich as fish, squirrels, ‘possums an’ ‘coons an’ ground hogs, an’ turkeys.52Lennis L. Broadfoot, Pioneers of the Ozarks (Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd, 1944).

|

| Zachariah McCannon, Searcy County miller Rick Horton discussing local corn varieties with University of Georgia anthropology graduate student James Veteto, Searcy County, 2009. |

Whereas early Ozark gristmills were usually water-powered, contemporary ones typically run on fossil fuels or electricity. The general disappearance of gristmills throughout the United States contributes to the decline in heirloom corn varieties because without a local miller, field or dent corn used for cornmeal, hominy, and grits, is suitable only as livestock feed.53Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 139. The Searcy County miller who grinds Willodean’s family corn works fulltime for the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission as a habitat biologist. He constructs and sells gas-powered gristmills and mills local families’ corn as a hobby. He estimates that only five to 10 percent of the corn brought for him to mill is hybrid, the other 90-95% is open-pollinated family corn. When a family brings him corn to be milled there is a fee for the service, unlike in the past when Ozark families had little (if any) cash money and instead paid a “miller’s fee,” a percentage of the corn. Willodean’s miller sets aside a small percentage of the corn unmilled in a deep freeze as seed stock to ensure that these family heirlooms are not lost. Several years ago one family planted all its seed corn and a severe storm washed it from their fields. The family was overjoyed when they contacted the miller and found that he had saved their corn seeds and their ancestral corn variety was not lost.

Agroecological Knowledge

Ozarkers who engage in agrobiodiverse farming have knowledge of their environment and the species within it that allow them to survive (agroecological knowledge). They utilize both wild and domesticated species, observe their behavior and interrelationships, and apply that information to use in gastronomy and agriculture. In the Ozarks and throughout the world, gourds (C. pepo,and Lagenaria siceraria) have found myriad uses.54Antonio Bisognin Dilson, "Origin and Evolution of Cultivated Cucurbits," Ciência Rural 32 (4)(2002), 715-723. Willodean and other Ozark farmers grow egg gourds (Cucurbita pepo) [also known as “nest” gourds] to use as surrogate eggs to indicate to a hen where she should be laying (rather than in hard-to-reach places) or to check the broodiness of a hen. Likewise, gourds have been grown on chicken houses to reduce or deter mite infestations55 Dilson, "Origin and Evolution of Cultivated Cucurbits." Nancy McDonough, Garden Sass: A Catalog of Arkansas Folkways (New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1975), 213. Gourd vines have an especially pungent, putrid smell and contain, like other members of the cucurbit family, a secondary metabolite called cucurbitacin. Cucurbitacin has been documented as an insect repellant and attractant, and a purgative, emetic, and antihelminthic, in addition to other medicinal applications for humans. This particular metabolite may assist the plant in repelling mites that affect chickens. Hard-shelled (Lagenaria) gourds serve as containers of different sorts, birdhouses, and toys, and as the bodies of the earliest banjos and fiddles.56Ballentine UCA Rackensack Oral History Collection

Wild Species

Willodean Smyth, like many contemporary Ozarkers and their ancestors, utilize wild foods, especially berries, in a range of dishes and beverages. Lissie Moffett of Turtle, Missouri, explained: I pick an’ can enough wild berries every summer to do me through the winter. I take my basket on my arm an’ go out into the hills an’ stay all day, pickin’ huckleberries an’ blackberries.57Broadfoot, Pioneers of the Ozarks, 148.

| Willodean's Ozark Mountain Grape Drink | |

| Wash and stir fresh, firm, ripe grapes. Put 1 cup of whole grapes into hot quart jars. Add ½ to 1 cup of sugar (I use 2/3 cups) fill jar with boiling water, leaving ¼ in headspace. Adjust cap, press quart in pressure cooker (5 lbs) or 10 minutes in boiling water bath. Wait about 3 few weeks for flavor to develop. |

A wide range of wild plants continue to be important in Ozark subsistence. Willodean references the most widely used and appreciated wild green in the Ozarks, American Pokeweed (Phytolacca Americana).58William McNeil, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992), 193. WPA Collection. She cans wild greens for her family to eat throughout the winter. Wild plants serve more than just culinary uses; they also provide medicine, stimulate growth in other plants, deter pests, and attract beneficial insects and pollinators.59Altieri, Agroecology. Michael Balick and Paul Cox, Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany (New York: Scientific American Library, 1996). Ozarkers harvest spring culinary greens, in this approximate order: 1) watercress (Nasturtium officinale), sticky thistle (Cirsium species), wild lettuce (Lactuea Canadensis), wild onions [garlic] (Allium species) 2) plantain (Plantago species), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), pokeweed, Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule), and broad-leaf (Rumex obtusifolius), and curley (Rumex crispus) dock 3) lamb's quarters (Chenopodium album), wild mustard (Brassica species), wild sage (Salvia lyrata) shepherd's purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), and along creek banks: crow's foot (Ranunculus Trichophyllus) and colt's foot (Tussilago farfara), and then last to emerge in May is sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella).60Nancy Holssinger, "Wild Greens: Values of the Roadside," Bittersweet 3(3)(1976), 52-57. Loma L. Paulson, "Greens Gathering through Generations," Bittersweet 3(3)(1976), 57-58. Randolph, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society, 33. Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks.

Pokeweed or poke sallit is a perennial plant that grows in just about any disturbed areas regardless of the quality of the soil. The ubiquity of the poke makes it a reliable food source even in the most stressed conditions. A folk tale collected in Stone County, Arkansas, in 1982 illustrates Ozarkers’ reliance on the plant, and their sense of humor:

Renzie Dow went to a place one night to stay. . . The man says come right on in. He says I do not have but one bed. You will have to sleep with me and my wife tonight. Says I will put a bolster [a long pillow] between us.

When time come to eat supper they did not have a thing in the world but poke salet. Renzie Dow was starving to death so he just eat poke salet until man it was a sight on earth, and the old man he reached over and he jerked the bowl away from him. He said . . . “to have some of that for breakfast; do not eat it all.”

Well, Renzie Dow was still just a starving to death. They went to bed and he was still laying there thinking about . . . all of that poke salet that he wanted. About midnight, why the stock just went to shouting out at the barn and all and the old man he had to go out and see what was bothering the stock. This woman . . . whispered to him. . . “now is your time.” Renzie Dow said, “huh?” and she says “now is your time, get over that bolster.” He said “Oh boy, I will get up and eat all of that poke salet.”61Rackensack Collection

The use of pokeweed as food requires knowledge of the plant’s properties, for it is poisonous if not cooked properly. Due to toxicity, only the young tender leaves are picked and boiled in water, and as Willodean explains, “boiled again” to ensure removal of the toxins.

Some plants produce toxic alkaloids and compounds to prevent herbivorous browsing, coincidently creating useful medicines or entheogens that lead to their increased propagation.62Balick and Cox, Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany. Michael Pollan, The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World (New York: Random House Books, 2001). The toxicity of pokeweed results in medicinal properties that Ozarkers have identified.63Justin M. Nolan and Michael C. Robbins, "Cultural Conservation of Medicinal Plant Use in the Ozarks," Human Organization 58(1)(1999), 67-72. Poke’s early spring shoots are considered an invaluable spring tonic.64Holssinger, Wild Greens, 58. McNeil, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook, 193. Historically, after the preserves were finished off, Ozarkers had only smoked meat and hunted game to eat in the latter half of the winter, which led to a “thickening” of the blood. Spring greens “thinned” the blood, thereby restoring health. The roots can be used in tinctures or bitters, a combination of alcohol (historically homemade corn whiskey) and medicinal herbs, and in decoctions to treat a range of ailments, especially rheumatism and arthritis, and as a general tonic. Some Ozarkers eat a poke berry a day for similar reasons (spitting out the seeds due to the “pizen” in them).

Traditional Ozark meals consist of cooked greens (sometimes mixed with eggs) and some form of pork served with a variety of beans and cornbread. An Arkansas WPA (Works Progress Administration) researcher in the 1930s recorded a recipe for “Poke Sallit, one of the best-liked spring vegetable dishes,” that concludes “Many persons like to pour pepper sauce on sallit at the table” and provides a recipe for this particular pepper sauce that includes vinegar and “freshly picked ripe bird peppers” (Capsicum Annuum). I have documented and collected heirloom seeds from a range of “bird peppers” in the area that have been variously referred to as Bouquet Peppers, Chiltepins, and Poinsettia Peppers.

|

| Brian C. Campbell, Poinsettia Peppers in the Seed Bank Heritage Garden, Greenbriar, Arkansas, 2008. |

The WPA recipe continues: “pot licker from poke greens as cooked in this way is particular-good eaten with corn bread.” Pot likker (licker) is the liquid left over after cooking greens and was commonly spread over cornbread. The cooked greens were usually poke, mustard (Brassica juncea) or turnip (Brassica rapa); the latter was the most common cultivated green. In Three Years in Arkansaw, Marion Hughes conveys the importance of turnip greens in early Ozark subsistence when he tells the story of a cow escaping into “John Brown’s garden and eat up his turnip greens, and John he sued [the cow’s owner] for maintenance until rostenears is hard enough to eat.”65Marion Hughes, Three Years in Arkansaw (Chicago: M.A. Donohue & Company, 1904), 44. The ubiquity of corn in traditional Ozark meals continues here, with the reference to “rostenears” [roasting ears]. This treatment of young field corn as a vegetable rather than a grain resembles our contemporary use of sweet corn.66West, Plainville, U.S.A., 45.

Frugality

|

| Brian C. Campbell, Ladybug on Whippoorwill field pea plant, Faulkner County, Arkansas, Seed Bank Heritage Garden, 2007. |

Growing species and varieties that tend to be well-adapted and resilient in their region, Ozarkers use (and reuse) plants that require limited work and inputs to produce and avoid the outlay of cash as much as possible. Field or cow peas (Vigna unguiculata) exemplify these traits and constitute another key foodways component.

Charles Morrow Wilson describes the Whippoorwill cowpea variety cooked with hog jowls as “distinctive Ozark fare.”67Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 157. The Whippoorwill pea – a hardy cowpea that survives the most extreme Ozark weather and readily self-seeds – was known to numerous Ozarkers as the food that “got them through the Depression.” In a 1979 inverview, the Avery brothers of Stone County, Arkansas said that when they were growing up their parents and grandparents referred to hard times as “eating peas and dance,” because that was all one could do then.68Rackensack Collection

|

| Vaughn Brewer, Lonnie and Asburn Avery, Stone County, Arkansas, September 6, 1979. Courtesy of University of Central Arkansas Archives, Rackensack Collection. |

|

| Brenda Smyth, Old chicken feed bags in garden with rocks on them as mulch, Searcy County, Arkansas, July 2009. |

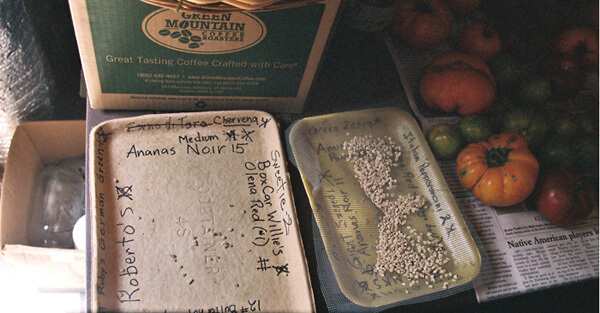

Willodean refuses to throw away feed bags because of their utility as garden mulch. The bags retain soil moisture and prevent weeds from outcompeting her desired crops. She reuses a wide range of containers and other materials. The foam trays from meats or other packaged store produce stacked in her kitchen pantry, remind me of another seed saver who uses these materials as seed drying trays. He is a back-to-the-land farmer who settled in Newton County, Arkansas, in the early 1980s, built his own home, and runs a plant nursery. He and his wife reuse a wide range of materials, from plastic bags and plastic garden pots to foam and cardboard trays for seed drying. In the past, Ozarkers resourcefully made use of torn clothing (rugs, quilts), corn cobs (fuel, pipes, dolls), shucks (chair bottoms, mats, brooms, mattress stuffing), old nails (fishing lures and gigs), and every part of an animal they slaughtered.69McDonough, Garden Sass. McNeil, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook. Old Stock seed savers continue to engage in recycling behavior because of their enculturation by parents who struggled through subsistence living and the Great Depression. Back-to-the-land seed savers may have different motivations for their recycling tendencies, such as more modern environmentalist and conservationist ideologies, but they share this dedication to frugality.

| |

| Brian C. Campbell, Seed Drying Trays, Newton County, Arkansas, 2009. Back-to-the-land farmer and seed saver Herb Culver. |

Before tossing any food to the pigs or chickens (rural waste disposals), traditional Ozarkers would have attempted to convert it into a palatable human dish. Willodean and her husband Kenneth recognize that some potatoes will inevitably get damaged during the harvest and they take measures to ensure that they do not go to waste. On April 6, 1973, Alice Dillard Smith of Marion County, Arkansas, wrote about her first “whipping” from her father, which she received for unintentionally “wasting” an entire crop of watermelons. She recalled:

We lived on a Rocky Ridge farm, which wasn’t good for raising watermelons. But one Spring they were Determined to raise some melons, they made Special hills some way. . . But it was good bit of work an trouble. We had a very nice patch of them an they had worked hard to establish some raised beds to grow them. It was time for melons to start Ripening. I was very small girl then an Id seen people plug melons to see if they were ripe. I didn’t know it would hurt them. So I got a knife one day an made for the patch. I plugged ever melon in the patch, not finding one Ripe one. I carefully placed the plugs back never dreaming I’d ruined them.70Alice Dillard Smith, Marion County, Arkansas, Unpublished, Hand-written Memoirs, acquired by Dr. Campbell from the family during ethnographic research in 2008.

While her mother tried to hide it from her father, the truth came out when he visited the patch, and Alice received a harsh lesson in Ozark subsistence.

At the end of the growing season in late fall, gardeners must salvage what they can before the first frost. Frequently tomatoes and other vegetables are picked before they are ripe and must be used in some unusual dish. Chow-chow fills that role by combining a hodge-podge of ingredients that may not suffice to make their own dish.

When a cucumber grows too large, it is no longer palatable, however Ozarkers, create innovative dishes that convert something that is usually wasted into something useful. Willodean turns the large over-ripe cucumbers into cinnamon rings. Here is a recipe for over-ripe zucchini squash.

| Lucy Monger's Mock Apple Butter | |

| 4 cups zucchini puree 6 tbs vinegar 3 tbs lemon juice | 2 cups sugar 1 tsp cinnamon (or more to taste) |

| Peel zucchini, take out the seeds, and chop coarsely. Place in blender with vinegar and lemon juice. Blend until smooth. Pour into saucepan with remaining ingredients. Blend well and cook on medium heat, stirring occasionally until mixture reaches desired thickness. Cool and keep in fridge or pour into sterilized pint jars while hot and seal. Serve with biscuits or toast. We use the large zucchini that seem to escape picking for this recipe. | |

| Willodean's Green Tomato Relish | |

| 12 cups ground or finely chopped tomatoes 4 cups chopped onions 3 chopped red and green bell peppers 8 cups boiling water 4 cups vinegar | 6 cups sugar ½ cup canning salt 3 tbs mustard seed 3 tbs celery seed (if wanted) 2 tbs turmeric |

| Combine tomatoes, onions, and peppers. Add boiling water, let set 5 or 10 minutes. Drain. Mix vinegar, sugar, salt, mustard, celery seeds and turmeric. Add to tomato mixture boil slowly for 15 or 20 minutes or until ready to can. Pour in jars and seal. Makes 6 pints. | |

The Future of Ozark Subsistence and Agricultural Biodiversity

While Willodean involves her grandchildren in gardening and canning and encourages them to consume healthy homegrown food, many children in the Ozarks are removed from these traditional processes.To encourage the continued transmission of agroecological knowledge and seed saving, several organizations have collaboratively established Seed Swaps. Today, agrobiodiverse farming in the Ozarks does not occur strictly among Old Stock farmers, rather a wide range of back-to-the-lander and new international immigrants. The Seed Swaps present a diversity of seed savers, in their ethnicity (Guatemalan, Mexican, Hmong, Thai) and in their age and farming background. Bo Bennett, a college student, excitedly traded his great grandfather’s seeds for other people’s grandparents’ seeds, exclaiming:

I’ve got some seeds. They’re Moon and Stars Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). I got these from my grandmother. They were my grandpa’s. He died ten years ago, but she saved this jar of seeds this whole time and never planted them. He grew them every year when he was alive and they were grown by my great-grandfather also.”

|  |  | ||

| John Hammer, Bo Bennett, UCA student, holding okra seed (left). He traded his grandfather’s Moon and Stars watermelon seed at the Swap. Victor Garcia of Independence County, Arkansas, and Kent Bonar, of Newton County, Arkansas (center). Willodean Smyth with her family heirloom variety Pencil Cob Corn (right). Ozark Seed Swap, Mountain View, Arkansas, 2009. | ||||

When Willodean attended her first Seed Swap and realized the interest so many people had in her varieties, knowledge, and traditions, she glowed. She was energized. She now seeks out local heirlooms more than ever, grows them in her gardens, gives them to the seed bank and at Swaps. She invites young people to her home and shows them how she cans. When she prepared butternut (C. moschata) and coushaw squash (C. mixta) pies for some neighbor “kids” (forty-somethings), they were shocked not to have eaten such food before. “Wow! I’ve never had this before," one remarked. "I can’t believe this food is so much better than store food.” “After hearing that,” Willodean says, “I decided, the good Lord has kept me alive because I’ve got a job to do, to teach young people how to make a garden and can.”

Recommended Resources

Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture. Boulder: Westview Press, 1995.

Blevins, Brooks. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Campbell, Brian. "'A gentle work horse would come in right handy': Animals in Ozark Agroecology," Anthrozoös: A multidisciplinary journal of the interactions of people and animals, 22(3) (2009): 239-253.

Campbell, Brian. "Ethnoecology of the Ozarks’ Agricultural Encounter," Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology, 48(1) (2009): 1-20.

Harington, Donald. Butterfly Weed. New Milford, CT: The Toby Press, 1996.

Heider, Karl G. Seeing Anthropology: Cultural Anthropology through Film, 4th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2006.

Massey, Ellen Gray. Bittersweet Country. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978.

McDonough, Nancy. Garden Sass: A Catalog of Arkansas Folkways. New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1975.

McNeil, William. An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Nazarea, Virginia. Heirlooms and their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005.

Rafferty, Milton. The Ozarks: Land and Life. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Shand, Hope. Human Nature: Agricultural Biodiversity and Farm-Based Food Security. Ottawa: RAFI, 1997.

West, James. Plainville, U.S.A. New York: Columbia University Press, 1945.

Wilson, Charles Morrow. The Bodacious Ozarks: True Tales of the Backhills. New York: Hastings House Publishers, 1959.

Links

Agroecology

http://www.agroecology.org/index.html.

Bioversity International

http://www.bioversityinternational.org/.

Convention on Biological Diversity

http://www.cbd.int/.

International Seed Saving Institute

http://www.seedsave.org/.

Saving Our Seed Project

http://www.savingourseed.org/.

| 1. | Donald Harington, Butterfly Weed (New Milford, CT: The Toby Press, 1996), 5. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Charles Morrow Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks: True Tales of the Backhills (New York: Hastings House Publishers, 1959), 28. |

| 3. | Brooks Blevins, Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). |

| 4. | Karl G. Heider, Seeing Anthropology: Cultural Anthropology through Film, 4th ed. (Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2006). Robert H. Lavenda and Emily A. Shultz, Core Concepts in Cultural Anthropology, 3rd ed. (Boston: McGraw Hill Companies, Inc., 2007). |

| 5. | Hope Shand, Human Nature: Agricultural Biodiversity and Farm-Based Food Security (Ottawa: RAFI, 1997). |

| 6. | Bill Balee and Darrell Posey, Resource Management in Amazonia: Indigenous and Folk Strategies (New York Botanic Garden series, Advances in Economic Botany, 1989). Nancy J. Turner, The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005). |

| 7. | Gary Paul Nabhan, Cultures of Habitat: On Nature, Culture, and Story (Washington DC: Counterpoint, 1997). Virginia Nazarea, Cultural Memory and Biodiversity (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1998). M.L. Oldfield and J.B. Alcorn, "Conservation of Traditional Agroecosystems," Bioscience, 37 (1997) 199-208. E. Smith and M. Wishnie, "Conservation and Subsistence in Small-scale Societies," Annual Review of Anthropology 29 (2000): 493–524. Nancy J. Turner, The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005). |

| 8. | Shand, Human Nature. |

| 9. | T. Johns, I.F. Smith, P. Eyzaguirre, "Understanding the Links Between Agriculture and Health" IFPRI, 13 (2006), 12-16. |

| 10. | M.A. Altieri, Agroecology: The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture (Boulder: Westview Press, 1995). Shand, Human Nature. |

| 11. | Altieri, Agroecology. T. Smith and Eyzaguirre, 2006. Eugene Odum, Ecology: A Bridge Between Science and Society (Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 1997). When the farmer focuses strictly on large-scale production of one crop for the market, the animals that previously produced manure for fertilizer, in addition to their meat, eggs, milk, or labor, must now be replaced with tractors, chemical fertilizers, and store-bought food. If the farmer moves to large-scale animal production, s/he must purchase large amounts of feed and abandon diversified production of crops. Instead of using manure as fertilizer, it becomes a point-source pollutant, requiring extensive mitigation measures to prevent groundwater pollution. Either way, a loss of self-sufficiency results. |

| 12. | Virginia Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers: Marginality and Memory in the Conservation of Biological Diversity (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005). J.W. Watson and P.B. Eyzaguirre, editors, "Proceedings of the Second International Home Gardens Workshop: Contribution of home gardens to in situ conservation of plant genetic resources in farming systems," 17–19 July 2001, Witzenhausen, Federal Republic of Germany. International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, 2002. |

| 13. | Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers. |

| 14. | B. Orlove and S. Brush, "Anthropology and the conservation of biodiversity," Annual Review of Anthropology 25 (1996), 329-352. |

| 15. | Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers, 16. |

| 16. | Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers, 19. |

| 17. | Milton Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001). |

| 18. | Tom Aley, "Karst Topography and Rural Poverty," Ozarkswatch 5.3 (1992), 19-21. |

| 19. | Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Vance Randolph, Pissing in the Snow, and other Folktales (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1976). |

| 20. | Brian Campbell, "Ethnoecology of the Ozarks’ Agricultural Encounter," Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology, 48.1(2009), 1-20. John Soloman Otto and Augustus Marion Burns III, "Traditional Agricultural Practices in the Arkansas Highlands," The Journal of American Folklore, 94 (1981), 166-187. Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. Vance Randolph, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society (New York: Vanguard Press, 1931). |

| 21. | Blevins, Hill Folks. W.O. Cralle, "Social change and isolation in the Ozark Mountain Region of Missouri," The American Journal of Sociology 41 (1936), 435–446. Art Gallaher Jr., Fifteen Years Later (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961). James West, Plainville, U.S.A. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1945). |

| 22. | Campbell, "Ethnoecology of the Agricultural Encounter in Ethnology." James R. Veteto, "The history and survival of traditional heirloom vegetable varieties in the southern Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina," Agriculture and Human Values 25 (2008), 121–134. K. Whealy, Foreword. In S. Stickland (ed), Heirloom Vegetables: A Home Gardener’s Guide to Finding and Growing Vegetables from the Past (New York: Fireside, 1998). |

| 23. | Nazarea, Heirlooms and their Keepers. Orlove and Brush, "Anthropology and the conservation of biodiversity," 342. |

| 24. | Gayle Fritz, "Identification of Cultigen Amaranth and Chenopod from Rockshelter Sites in Northwest Arkansas," American Antiquity, Vol. 49 No. 3 (1984), 558-572. George Sabo and Jerry E. Hilliard, "Woodland Period Shell-Tempered Pottery in the Central Arkansas Ozarks," Southeastern Archaeology, Winter 2008. |

| 25. | Kenneth L. Smith, Buffalo River Handbook (Little Rock, AR: The Ozark Society, 2004). |

| 26. | Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. |

| 27. | Timothy Jones, "Commentary on 'Cultural Conservation of Medicinal Plant Use in the Ozarks.'" Human Organization 59(1)(2001), 136-140. |

| 28. | Blevins, Hill Folks. Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. |

| 29. | Russel L. Gerlach, Immigrants in the Ozarks : A Study in Ethnic Geography (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1976). |

| 30. | Blevins, Hill Folks, Campbell n.d. |

| 31. | Blevins, Hill Folks, 200. |

| 32. | Harington, Let Us Build Us a City: Eleven Lost Towns. (New Milford, CT: The Toby Press, 1986), 98-9. |

| 33. | Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. |

| 34. | Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. |

| 35. | Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 152. |

| 36. | Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 164-5. |

| 37. | Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 28. |

| 38. | Robert Rhoades, "Integrating Local Voices and Visions into the Global Mountain Agenda," Mountain Research and Development 20(1)(2000), 4-9. |

| 39. | Rafferty, The Ozarks: Land and Life. |

| 40. | While animals constitute a very significant component of traditional Ozark subsistence, this research focuses exclusively on the diversity of the home garden and cellar (for more on animals in traditional Ozark agroecology see Brian Campbell, "'A gentle work horse would come in right handy': Animals in Ozark Agroecology," Anthrozoös: A multidisciplinary journal of the interactions of people and animals, 22(3) (2009), 239-253). |

| 41. | West, Plainville, U.S.A., 37. |

| 42. | Alice Dillard Smith (born 1894), Unpublished, hand-written memoirs. Marion County, Arkansas. |

| 43. | Rackensack Collection, unpublished oral histories conducted in Stone County, Missouri in association with Jimmy Driftwood. University of Central Arkansas Archives. Conway, Arkansas. |

| 44. | Erin McCawley Renn, "German Food: Customs and Traditions in the Missouri Ozarks," Ozarkswatch 3(3) (1990), 14-19. |

| 45. | William McNeal, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992). |

| 46. | Ellen Gray Massey, Bittersweet Country (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1978), 40. |

| 47. | Dana Hamilton, My Daddy Taught Me to Doctor Snake Bites! Mozark: Cultural Journalism of Madison County, Missouri High School English Class (Fredericktown Missouri Public Library Collection, 1982), 56. |

| 48. | Suzanne Ashworth, Seed to Seed: Seed Saving and Growing Techniques for Vegetable Gardeners (Decorah IA: Seed Savers Exchange Press, 2002). |

| 49. | Massey, Bittersweet Country. |

| 50. | S.B. Brush, Genes in the Field, On-Farm Conservation of Crop Diversity (Boca Raton, FL: Lewis Publishers, 2000). |

| 51. | Blevins, Hill Folks, 22. |

| 52. | Lennis L. Broadfoot, Pioneers of the Ozarks (Caldwell, Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd, 1944). |

| 53. | Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks, 139. |

| 54. | Antonio Bisognin Dilson, "Origin and Evolution of Cultivated Cucurbits," Ciência Rural 32 (4)(2002), 715-723. |

| 55. | Dilson, "Origin and Evolution of Cultivated Cucurbits." Nancy McDonough, Garden Sass: A Catalog of Arkansas Folkways (New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, 1975), 213. Gourd vines have an especially pungent, putrid smell and contain, like other members of the cucurbit family, a secondary metabolite called cucurbitacin. Cucurbitacin has been documented as an insect repellant and attractant, and a purgative, emetic, and antihelminthic, in addition to other medicinal applications for humans. This particular metabolite may assist the plant in repelling mites that affect chickens. |

| 56. | Ballentine UCA Rackensack Oral History Collection |

| 57. | Broadfoot, Pioneers of the Ozarks, 148. |

| 58. | William McNeil, An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992), 193. WPA Collection. |

| 59. | Altieri, Agroecology. Michael Balick and Paul Cox, Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany (New York: Scientific American Library, 1996). |

| 60. | Nancy Holssinger, "Wild Greens: Values of the Roadside," Bittersweet 3(3)(1976), 52-57. Loma L. Paulson, "Greens Gathering through Generations," Bittersweet 3(3)(1976), 57-58. Randolph, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society, 33. Wilson, The Bodacious Ozarks. |

| 61. | Rackensack Collection |