Overview

The Black Belt

|

| Traditional Counties of the Alabama Black Belt. |

In the 1820s and 30s, the Black Belt identified a strip of rich, dark, cotton-growing dirt drawing immigrants primarily from Georgia and the Carolinas in an epidemic of "Alabama Fever." Following the forced removal of Native Americans, the Black Belt emerged as the core of a rapidly expanding plantation area. Geologically, the region lies within the Gulf South's Coastal Plain in a crescent some twenty to twenty-five miles wide that stretches from eastern, south-central Alabama into northwestern Mississippi. The unusually fertile Black Belt (or Prairies) soil is produced by the weathering of an exposed limestone base known as the Selma Chalk, the remnant of an ancient ocean floor.

Selma Chalk photographs from 1914 US Geological Survey “Cretaceous Deposits of the Eastern Gulf Region,” Selma, Alabama, ca. 1914. Image uploaded by Flickr user Internet Archive Book Images. Image is in the public domain.

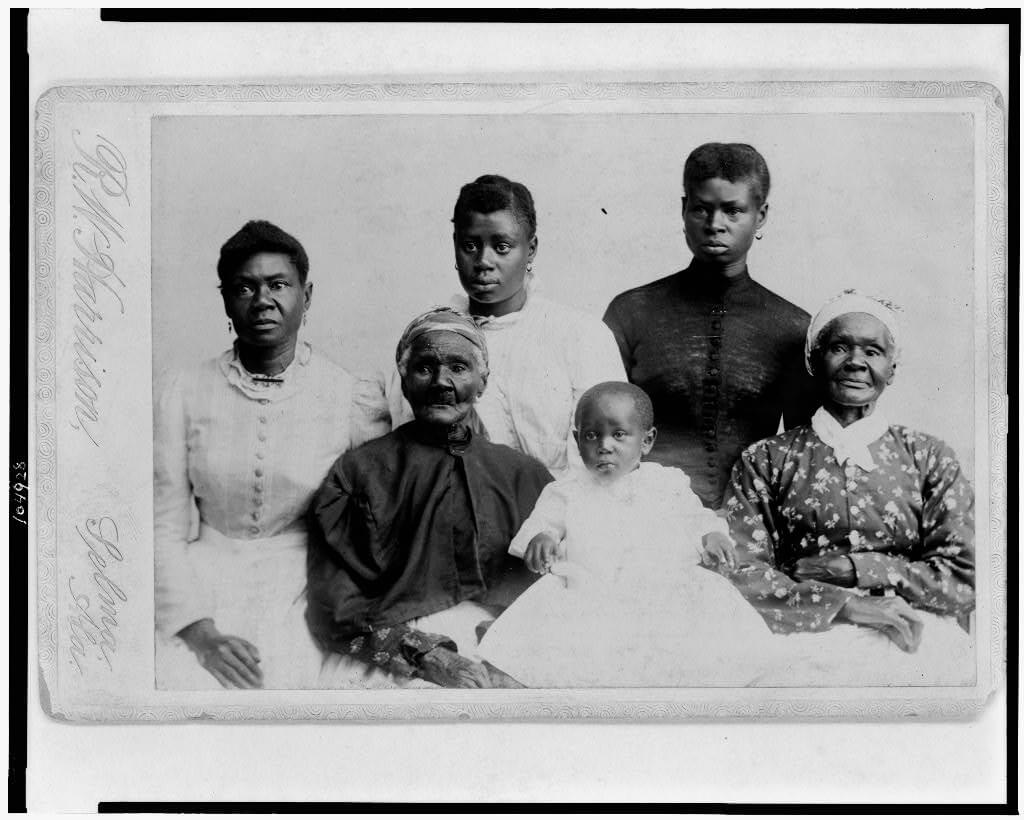

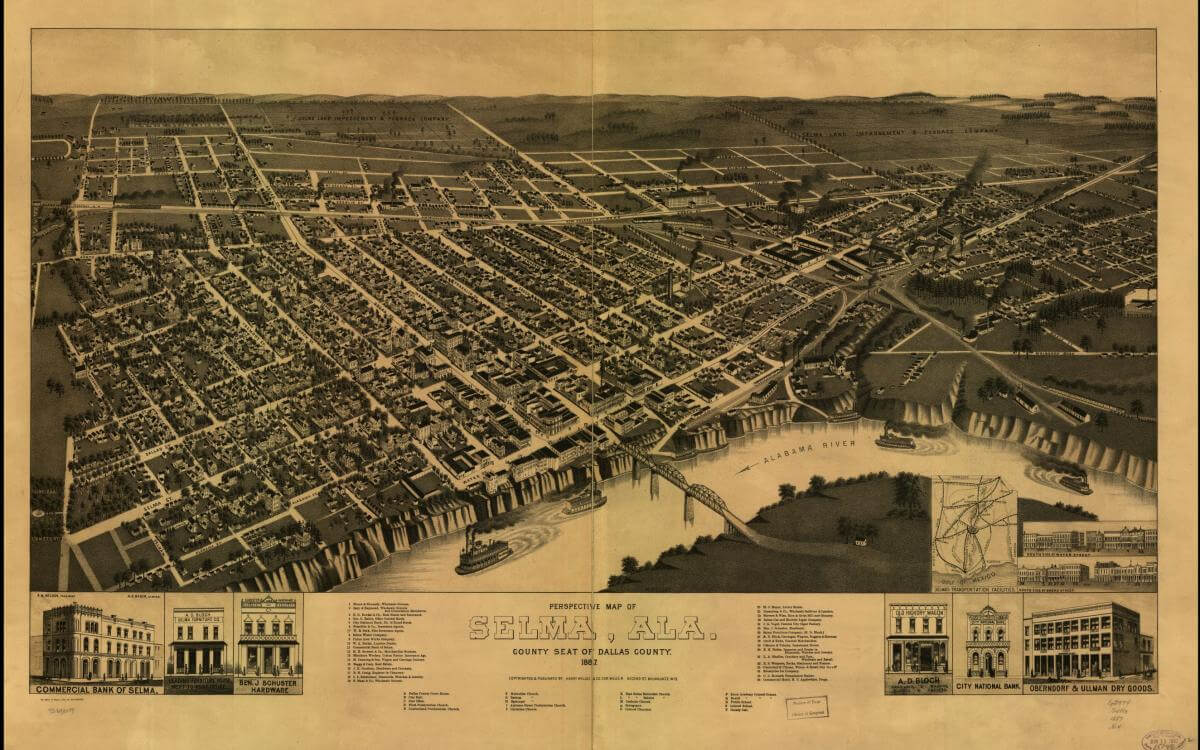

Half of Alabama's enslaved population was concentrated within ten Black Belt counties where the exploitation of their labor made this one of the richest regions in the antebellum United States. During the "flush times," Black Belt commerce on the Alabama, Black Warrior, and Tombigbee rivers transformed towns such as Montgomery, Selma, Demopolis, and Tuscaloosa and boosted the Gulf Coast port of Mobile.

Pro-slavery secessionist sentiment in the Black Belt led Alabama into the Confederacy in 1861. Briefly, following emancipation and the South's military defeat, African Americans first went to the state's polls in 1867 and held a variety of local, state, and national political offices. With the mid-1870s however, came the restoration of white rule. Then, "for a hundred years," wrote Selma civil rights attorney J. L. Chestnut in his 1990 autobiography, "the Black Belt dominated state politics and the big landowners dominated the Black Belt."

Through violence, appeals to white supremacy, and massive voter fraud, the Black Belt's oligarchs defeated the 1890s challenge of the Populists and inscribed their power in a straitjacket of a state constitution that disfranchised the African American population along with many poor whites. This 1901 Alabama constitution, concluded historian Wayne Flynt, would keep Alabama "throughout the twentieth century at or near the bottom among all states in . . . property taxes, public services, and quality of life."

Black and white portrait of Booker T. Washington from Bain News Service, ca. 1900. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/ggb2004005046/

A second meaning of Black Belt as a region or place with majority-black population grew as a consequence of the expansion of slavery throughout the southern states. "I have often been asked to define the term 'Black Belt,'" commented Booker T. Washington in 1901:

So far as I can learn, the term was first used to designate a part of the country which was distinguished by the colour of the soil. The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturaly rich soil was, of course, the part of the South where the slaves were most profitable, and consequently they were taken there in the largest numbers. Later, and especially since the war, the term seems to be used wholly in a political sense — that is, to designate the counties where the black people outnumber the white.

Beyond its multi-county Alabama designation, the Black Belt as a landscape of primarily cotton agriculture and majority African American population covered a swath from Virginia through the Carolinas and across the Gulf South. In 1903, W. E. B. DuBois sought to describe African American life in the “heart of the Black Belt” by focusing, in Souls of Black Folk, upon a south Georgia county.

The Communist Party in the 1920s and 30s called for the right of self-determination for a Deep South "Black Belt nation." In his study of tenancy in two Georgia counties, Preface to Peasantry (1936), sociologist Arthur Raper understood the Black Belt as some two-hundred plantation counties "in which over half the population is Negro" lying "in a crescent from Virginia to Texas."

With decades of steady out-migration from the South, the Black Belt also came to mean those parts of northern cities having heavy African American populations. Making the 1927 journey described in Black Boy (American Hunger), Richard Wright traveled from Mississippi and Tennessee to arrive among tens of thousands of African American migrants clustered in Chicago’s north side. Wright commented that he crossed the “boundary line of the Black Belt” in order to enter the south side, “that territory where jobs were perhaps available to be had from white folks.” Finding night work, he turned his daytime attention to “experimental writing, filling endless pages with stream-of-consciousness Negro dialect, trying to depict the dwellers of the Black Belt as I felt and saw them.”

In the first half of the twentieth century, years of soil erosion, the boll weevil invasion, the collapse of cotton tenancy, the failure to diversify economically, the urban exodus, and the repressive era of Jim Crow all combined to mire the southern Black Belt in a seemingly irreversible decline. What had been one of America's richest and most politically powerful regions became one of its poorest.

In the 1950s and 1960s, long-oppressed African American residents of the Alabama Black Belt, aided by Supreme Court decisions and congressional actions, transformed small towns such as Tuskegee, Marion, Selma, Hayneville, and Eutaw into scenes of some of the most critical moments of the modern American freedom struggle. In the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott, the figures of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. helped bring international attention to the mass mobilization for civil rights. At lunch counters, in city parks, on courthouse squares, in registrars’ offices, and on the highways and backstreets, thousands of citizens challenged the historical spaces and practices of segregation.

The Selma to Montgomery March, now commemorated by a National Historic Trail, led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Beginning with the election of the nation's first black probate judge in Greene County in the late 1960s, grassroots activism resulted in the coming to office of black sheriffs, county commissioners, county school boards, mayors, and city council members. In a generation, the Black Belt could count the largest concentration of African American elected officials in the US.

The Alabama Black Belt as a region of insurgent African American aspirations makes a strong claim to take over the meaning of the term from its older and other senses. The electoral transformation here, however, remains thwarted in efforts to tap the economic resources of this region which generates wealth for a small number of individual landowners and for international timber and paper corporations. Cottonfields no more, but pine tree plantations, cattle pastures, and hunting leases cover tens of thousands of acres of the Black Belt, its property owners benefiting from one of the most regressive tax structures in the nation. Segregated education remains a common practice due to white flight into private Christian academies.

Cultural tourism and commemorative events such as Civil War reenactors blowing smoke at the Battle of Selma and human rights pilgrims annual crossing of the Edmund Pettus Bridge dramatize two moments of conflict at the heart of the Black Belt's history.

From this region of continuing economic inequality, African American women quilters regularly emerge to dazzle visitors to the Smithsonian Institution's Festival of American Folklife and aficianados of modern art at New York City's Whitney Museum. To the Black Belt, in increasing numbers each year, visitors from throughout the world come to trace the landscape and ponder the region's hard and far-from-finished lessons.

Recommended Resources

Text

Beardsley, John and William Arnett, et al. Gee's Bend: The Women and Their Quilts. Atlanta: Tinwood Books and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2002.

Chestnut, J.L. Jr., and Julia Cass. Black in Selma. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990.

Clay, James W and Paul D. Escott, Douglas M. Orr, Jr., and Alfred Stuart. Land of the South. Birmingham: Oxmoor House, 1989.

Raper, Arthur F. Preface to Pesantry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1936.

Rogers, William Warren, and Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt. Alabama: The History of a Deep South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1994.

Thomson, Bailey ed.. A Century of Controversy: Constitutional Reform in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

Washington, Booker T. Up From Slavery. Norton Critical Edition. William L. Andrews, ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996.

Wright, Richard. Black Boy (American Hunger) in Later Works. New York: Library of America, 1991.

Wimberley, Ronald C. and Libby V. Morris.The Southern Black Belt: A National Perspective. Lexington: TVA Rural Studies and The University of Kentucky, 1997.

Web

Slavery in 1860, US counties. Visit the American Memory site and Search for "map showing the distribution of the slave population". http://memory.loc.gov/

Twenty Five Years in the Black Belt: Electronic Edition. First person history by William Edwards, b. 1869. (From Documenting the American South. Univ. of NC). http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/edwards/edwards.html

J. R. Moehringer's 2000 Pulitizer Prize winning portrait of Gee’s Bend, an Alabama Black Belt river community.

http://www.pulitzer.org/citation/2000-Feature-Writing

A recent effort to configure the broadly-defined southern Black Belt into a federally-authorized commission along the lines of the Appalachian Regional Commission has not succeeded. (From Vinson Institute, University of Georgia).

http://web.archive.org/web/20060901091247/http://www.cviog.uga.edu/spotlight/news/item.php?id=19

Mohr, James and John Nicols, "Cotton Production in the American South: 1790-1860" interactive map from Mohr and Nicols, eds., Mapping History: The Darkwing Atlas Project, Department of History, University of Oregon.

Barry, Dan. "Legacy of School Segregation endures, Separate but Legal," New York Times, Sep 30, 2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/30/us/30land.html?ref=us