Overview

The emergence of the African American community in Atlanta during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries reveals the constraints and opportunities that characterized the development of the leading city of the New South.

Community Building in a New South City

Atlanta offers a sharp perspective of the Black experience in the urban South during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The emergence of its Black community reveals the constraints and opportunities that characterized Atlanta's development as the leading city of the New South. Born a railroad terminus in the 1840s, Atlanta was a town of less than 10,000 people at the start of the Civil War. Rebounding quickly after the devastation by Sherman's army, however, Atlanta grew phenomenally to nearly 22,000 people by 1870.

As the major railroad hub in the South, Atlanta became a commercial and financial center. Although the city's business leadership was a new elite, its economy depended on many ways on the old cash crop. The rail network distributed cotton throughout and beyond the South and stimulated in Atlanta the growth of banks and brokerages, mills and factories. Atlanta was the shining example of Henry Grady's New South ideology — seeking industrialization through northern capital and promising racial justice through segregation. But in spite of the city's aggressive promotion of its economic agenda and its myth of racial stability, Atlanta, like the rest of the South, would for the next several decades struggle for a New South economy under the old racial order. The city's African American population contended with the framework of this struggle.

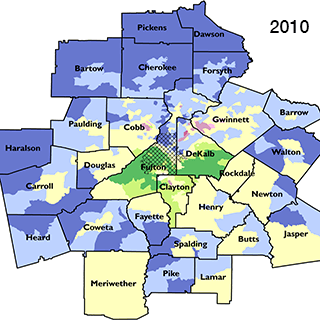

In 1870, Blacks accounted for nearly half of Atlanta's population. As free persons they competed for jobs and living space with whites, many of whom, like themselves, were poor migrants from the Georgia piedmont. Without slavery to ensure white supremacy, white southerners developed a system of racial segregation so encompassing and effective that it overturned the limited gains of Reconstruction and guaranteed the subordination of Blacks in every area of life. Jim Crow, as the system became known, had its full flowering in cities like Atlanta where economic access, political power, and social interaction were denied or severely restricted. Blacks were confined to the lowest status, lowest paying jobs, disfranchised by the white primary, and segregated in neighborhoods, schools, parks, libraries, restaurants, and other facilities. Black Atlantans were concentrated in two areas of the city located east and west of downtown. Although most were common laborers, a small number, perhaps less than ten percent, stood above the masses by virtue of their occupation, education, or income. These were the businessmen, educators, clergy, and other professionals, who ironically served the old racial order.

Following Emancipation and before Jim Crow's entrenchment, the services that slaves had performed offered the best business opportunities for freed Blacks. In a booming economy like Atlanta's, a few Blacks made a good income catering to whites in personal services such as barbering, shoemaking, tailoring and dressmaking, and in building trades like masonry, carpentry, and plastering. Generally locating their establishments in downtown along Peachtree, Broad, Marietta and adjacent streets, they were the core of the Black business elite, an upper class relative to the Black masses, but middle class by white standards. An estimated two percent of Black Atlantans like Alonzo Herndon, the city's premier barber, had substantial business earnings and real estate, qualifying by any measure for upper income status.

The institutional development of Black Atlanta was as phenomenal as its business enterprise. As the Black population in Atlanta grew five-fold in five years after Emancipation, so too did the number of its churches increase greatly. Having worshipped during slavery in segregated pews in white churches or in independent Black churches under the supervision of whites, as was the arrangement for Bethel African Methodist Episcopal and Friendship Baptist, Blacks were eager for religious autonomy. Mutual aid societies were the natural outgrowth of churches seeking to meet their members' financial emergencies in sickness and death. The support of schools, however, was perhaps the church's most significant social endeavor. Since the Atlanta public school system did not begin operations until 1872 and had only three grammar schools for Blacks, early Black education in Atlanta is primarily the story of private institutions supported by local Black churches and White northeastern mission societies. Within twenty-three years of Emancipation, five Black private schools in Atlanta were founded: Clark, Spelman, Morehouse, and Morris Brown colleges and Atlanta University. Atlanta had become a regional center for Black higher education.

When Booker T. Washington delivered his "Atlanta Compromise" speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in 1895, the triumph of Jim Crow in law and custom was virtually complete. Washington addressed the fears of many whites and the hopes of some Blacks when he pleaded for accommodation to political and social inequality for the sake of economic progress. His speech echoed Henry Grady's appeal in the previous decade for economic growth and racial reconciliation within the structures of white supremacy.

|

| Photographer unknown, Atlanta Life Insurance Company branch office staff, circa 1922. Courtesy of the Herndon Home. |

By the turn of the twentieth century, a more firmly established Jim Crow had altered the constraints and opportunities for Black community-building in Atlanta. Black businessmen, increasingly excluded from their traditional trades, were forced to find a market among their own race. The Riot of 1906, in which white mobs massacred Blacks, underscored the failures of accommodation, confirming that violence, not justice, was the reality of Jim Crow. For protection, survival, and uplift, the Black community had to rely more heavily on its own resources and seek new strategies. W. E. B. Du Bois, a professor of history and economics at Atlanta University, challenged the compromise that Washington had negotiated in Atlanta. In 1905, he and others founded the Niagara Movement, the first twentieth century civil rights organization to seek full citizenship rights. On the economic front, Black cooperation and self-sufficiency gave rise to one of the most significant Black commercial districts in the United States. Along Auburn Avenue in the Fourth Ward on the east side, where most of Atlanta's Black elite lived, a new stage of enterprise unfolded. An African American market that had grown nearly four times its post-war size could support a comprehensive mix of businesses. Auburn Avenue was virtually a separate economy behind the color line. Not only were there barbershops, drugstores, restaurants, and office complexes, but also, like the characteristic components of Atlanta's economy, there were banks and insurance companies. From the profits he amassed in barbering, Alonzo Herndon capitalized Atlanta Life Insurance Company, which became the city's leading Black business. Auburn Avenue would have its heyday from the 1930s through the 1950s, thriving on the crest of segregation. The civil rights movement of the 1960s, however, in eliminating the major barriers to political participation and public accommodations, would usher in a new stage of Black community-building on the city's west side, leaving Auburn Avenue without its market, without its reason for being.

Recommended Resources

Carter, Edward R. The Black Side: A Partial History of the Business, Religious, and Educational Side of the Negro in Atlanta, GA. Atlanta, 1894.

Doyle, Don H. New Men, New Cities, New South: Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston, Mobile, 1860-1910. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Du Bois, W. E. B. Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903.

Harlan, Louis. Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901-1915. Oxford University Press, 1983.

Henderson, Alexa. Atlanta Life Insurance Company: Guardian of Black Economic Dignity. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Jones, Jacqueline. Soldiers of Light and Love: Northern Teachers and Georgia Blacks, 1865-1873. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

Kuhn, Clifford M., Harlon E. Joye, and E. Bernard West. Living Atlanta: An Oral History of the City, 1914-1948. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990.

Meier, August and David Lewis. "History of the Negro Upper Class in Atlanta, Georgia 1890-1958." Journal of Negro Education 28 (spring 1959):128-39.

Merritt, Carole. The Herndons: An Atlanta Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. 3d ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.