Overview

In this essay, Matthew Delmont examines four programs that brought music and dance to southern and border state television audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. Arguing that television provided creative outlets for some black teens during segregation, Delmont focuses on three black teen shows, The Mitch Thomas Show from Wilmington, Delaware (1955–1958), Teenage Frolics (1958–1983), hosted by Raleigh, North Carolina, deejay J. D. Lewis, and Washington, DC's Teenarama Dance Party (1963–1970) hosted by Bob King. Delmont also explores Washington, DC's whites-only program, The Milt Grant Show (1956–1961), to highlight the pronounced color lines that informed the experience of teenage dancers, as well as the home and studio audiences that flocked to these hit shows.

Soundings is an ongoing series of interdisciplinary, multimedia publications that use historical, ethnographic, musicological, and documentary methods to map and explore southern musics and related practices. This series is guest edited by Grace Elizabeth Hale, Commonwealth Chair of American Studies, professor of history, and director of the American Studies Program at the University of Virginia.

When Chuck Willis released his single "Betty and Dupree" in 1958, he and Atlantic Records wanted to keep teenagers across the country dancing the Stroll. Willis's "C. C. Rider" (1957) sparked the popularity of the dance and earned Willis the nickname "The King of the Stroll." Like much of American popular music, Willis and his songs had deep roots in the South. Willis was born in Atlanta and his version of "C. C. Rider" was a remake of the popular blues song "See See Rider Blues," which was first recorded and copyrighted by Columbus, Georgia, native Ma Rainey in 1924.1Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, vocal performance of "See See Rider Blues" by Ma Rainey and Lena Arant, recorded October 16, 1924, by Paramount, catalogue number 12252, 78 rpm. With "Betty and Dupree," Willis revived a folk song, first recorded as "Dupree Blues" in 1930 by Blind Willie Walker from Greenville, South Carolina. Walker's song, in turn, was based on the story of Frank Dupre, who was hanged in Atlanta after stealing a diamond ring for Betty Andrews and shooting a detective.2Jeff Todd Titon, Early Downhome Blues: A Musical and Cultural Analysis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977), 74–75; Tom Hughes, Hanging the Peachtree Bandit: The True Tale of Atlanta's Infamous Frank Dupree (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014).

The teenagers in this clip from Seventeen, a teen dance show broadcast by WOI-TV to central Iowa in the late-1950s, did not need to know this history to appreciate that Willis's "Betty and Dupree" was a perfect song for dancing the Stroll, even if they did so awkwardly. The teens on Seventeen were emulating their peers in Philadelphia who popularized the dance on the nationally broadcast American Bandstand. Less obviously, the Iowa teens were also emulating teens on The Mitch Thomas Show—a black teen dance show that broadcast locally from Wilmington, Delaware, to the Philadelphia area—whose version of the Stroll influenced the American Bandstand dancers.

While Des Moines, Iowa, may be a long way from the South geographically, television connected Iowa teens to music and dance styles flowing from Delaware, Georgia, South Carolina, and elsewhere. Seventeen was one of dozens of locally broadcast teen dance shows in this era. Each show featured musical performances and records alongside dancing teenagers. The simplicity and profitability of the teen dance show format appealed to television stations, but airing images of youth music culture was a complicated proposition that involved television technologies, network affiliations, marketing, and racial segregation. This essay examines four programs that brought music and dance to southern and border state audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. I focus on three black teen shows, The Mitch Thomas Show from Wilmington, Delaware (1955–1958); Teenage Frolics (1958–1983), hosted by Raleigh, North Carolina, deejay J. D. Lewis; and Washington, DC's Teenarama Dance Party (1963–1970), hosted by Bob King. In addition, I examine Washington's The Milt Grant Show (1956–1961), which allowed only white dancers.

These shows broadcast in an era when civil rights lawsuits and protests sought to overturn policies of racial segregation in schools and public spaces in the South. Wilmington and Washington were the sites of two of the school segregation cases, Belton v. Gebhart and Bolling v. Sharpe, which the Supreme Court combined into Brown v. Board of Education. In Raleigh, token school integration did not begin until 1960, six years after Brown.3Sarah Caroline Thuesen, Greater Than Equal: African American Struggles for Schools and Citizenship in North Carolina, 1919 –1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 225–229. That same year, black students from St. Augustine University and Shaw University staged sit-ins at lunch counters in Raleigh to protest the whites-only policies at Woolworths and other stores.4Jeffrey Crow, Paul Escott, and Flora Hatley, A History of African Americans in North Carolina (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1992). Televisual representations and photographs of civil rights protests in Little Rock, Greensboro, Birmingham, Jackson, Selma, and other cities also made images of the South highly politicized.5Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012); Martin Berger, Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011); and Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). Part of the power of television for civil rights activists was how the medium exposed excessive acts of physical violence to audiences outside the South. In the midst of the voting rights marches in Selma in 1965, for example, Martin Luther King told marchers and the news media, "We are here to say to the white men that we no longer will let them use clubs on us in the dark corners. We're going to make them do it in the glaring light of television."6Quoted in Bodrogkozy, Equal Time, 2.

In the context of pitched battles over segregation and civil rights, these televised teen dance shows reveal much about the visibility of different youth musical cultures in the 1950s and 1960s. First, The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama Dance Party were important for black teens because the shows offered televisual spaces that valued their creative energies and talents. As historian Earl Lewis has noted, when African Americans faced Jim Crow policies in parks, swimming pools, and movie theaters, they developed separate recreation sites through which they turned segregation into "congregation."7"Afro-Americans who lived in communities as diverse as Chicago, Norfolk, and Buxton, Iowa, congregated—sometimes along class lines, but always together," Earl Lewis argues. "In the southern context, congregation was important because it symbolized an act of free will, whereas segregation represented the imposition of another's will." Earl Lewis, In Their Own Interests: Race, Class, and Power in Twentieth-Century Norfolk, Virginia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 91–92. Unlike other racially segregated leisure spaces, however, television brought the sounds and images of black music cultures to viewers of all colors across and beyond the cities from which the shows broadcast. Second, television technology worked to enhance and/or limit the visibility of different youth musical cultures. Broadcasting from Wilmington, Raleigh, and Washington, these shows reached regional audiences, but varied in terms of signal strength and network affiliations. Differences in terms of station power and stability shaped the duration of each program. Finally, the visibility these shows offered to teenagers was closely tied to the salability of teen music culture. For The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama Dance Party this meant trying to attract sponsors to advertise to black television audiences. For The Milt Grant Show, this meant airing black music performances while maintaining a segregated studio audience that would appeal to sponsors.

I became interested in these teen dance shows while researching and writing a book on American Bandstand. Counter to host Dick Clark's claims that he integrated American Bandstand, my research revealed how the first national television program directed at teens discriminated against black youth during its early years and how black teens and civil rights advocates protested this discrimination.8Matthew Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). Like American Bandstand, the local programs I explore in this essay brought dynamic music cultures to eager audiences and advertisers, while they also traced the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion in their cities. Unlike American Bandstand, or Soul Train, which started broadcasting nationally in 1971, The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, Teenarama Dance Party, and The Milt Grant Show are not well known outside of their local broadcast markets. Among these four programs, only one recording is known to exist, a 1957 episode of The Milt Grant Show recorded to sell the show to sponsors. With limited televisual evidence, my analysis draws on archival documents, promotional materials, newspapers, photographs, and interviews to explore how these shows got on and stayed on the air and what they meant to their audiences. By examining these local programs this essay builds on the work of scholars Norma Coates, Murray Forman, Julie Malnig, Tim Wall, George Lipsitz, and Brian Ward who have examined the intersections of music and television, the importance of televised teen dance shows as community spaces, and the development of rhythm and blues and rock and roll.9Norma Coates, "Elvis from the Waist Up and Other Myths: 1950s Music Television and the Gendering of Rock Discourse," in Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones, eds. Roger Beebe and Jason Middleton (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 226–251; Coates, "Filling in Holes: Television Music as a Recuperation of Popular Music on Television," Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 1, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 21–25; Murray Forman, One Night on TV Is Worth Weeks at the Paramount: Popular Music on Early Television (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Julie Malnig, "Let's Go to the Hop: Community Values in Televised Teen Dance Programs of the 1950s," Dance & Community: Proceedings of The Congress on Research in Dance (August, 2006): 171–175; Tim Wall, "Rocking Around the Clock: Teenage Dance Fads from 1955 to 1965," in Ballrooms, Boogie, Shimmy, Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader, ed. Julie Malnig (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 182–198; George Lipsitz, Midnight at the Barrelhouse: The Johnny Otis Story (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); and Brian Ward, Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race Relations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

The Mitch Thomas Show

The Mitch Thomas Show debuted on August 13, 1955, on WPFH, an unaffiliated television station that broadcast to Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley from Wilmington.10"The NAACP Reports: WCAM (Radio)," August 7, 1955, NAACP collection, URB 6, box 21, folder 423, TUUA. Born in West Palm Beach, Florida, Mitch Thomas graduated from Delaware State College and served in the army before becoming the first black disc jockey in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1949.11Eustace Gay, "Pioneer In TV Field Doing Marvelous Job Furnishing Youth With Recreation," Philadelphia Tribune, February 11, 1956; Gary Mullinax, "Radio Guided DJ to Stars," The News Journal Papers (Wilmington, DE), January 28, 1986, D4. His television show, broadcast every Saturday, resembled Philadelphia's Bandstand, at the time a local program hosted by Bob Horn, and other locally broadcast teenage dance programs. The Mitch Thomas Show stood out because it was the first television show hosted by a black deejay that featured a studio audience of black teenagers. Otis Givens, who lived in South Philadelphia and attended Ben Franklin High School, remembered that he watched the show every weekend for a year before he finally made the trip to Wilmington to dance on air. "When I got back to Philly, and everyone had seen me on TV, I was big time," Givens recalled. "We weren't able to get into Bandstand, [but] The Mitch Thomas Show gave me a little fame. I was sort of a celebrity at local dances."12Otis Givens, interview with author, June 27, 2007. Similarly, South Philadelphia teen Donna Brown recalled in a 1995 interview, "I remember at the same time that Bandstand used to come on, there used to be a black dance thing that came on, and it was The Mitch Thomas Show . . . And that was something for the black kids to really identify with. Because you would look at Bandstand and we thought it was a joke."13Quoted in John Roberts, From Hucklebuck to Hip-Hop: Social Dance in the African American Community in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Odunde, 1995), 37. The Mitch Thomas Show also became a frequent topic for the black teenagers who wrote the Philadelphia Tribune's "Teen-Talk" columns. Much in the same way that national teen magazines followed American Bandstand, the Tribune's teen writers kept tabs on the performers featured on Thomas's show, and described the teenagers who formed fan clubs to support their favorite musical artists and deejays.14On the Philadelphia Tribune's "Teen-Talk" coverage of Mitch Thomas' show, see "They're 'Movin' and Groovin,'" Philadelphia Tribune, July 31, 1956; Dolores Lewis, "Talking With Mitch," Philadelphia Tribune, November 9, 1957; Lewis, "Stage Door Spotlight," Philadelphia Tribune, November 9, 1957; Laurine Blackson, "Penny Sez," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957 and April 26, 1958; Dolores Lewis, "Philly Date Line," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957; "Queen Lane Apartment Group [photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957; Jimmy Rivers, "Crickets' Corner," Philadelphia Tribune, January 21 and April 22, 1958; Edith Marshall, "Current Hops," Philadelphia Tribune, March 1, 8 and 22, 1958; Marshall, "Talk of the Teens," Philadelphia Tribune, March 22, 1958; and "Presented in Charity Show [Mitch Thomas photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, April 22, 1958. The fan gossip shared in these columns documented the growth of a youth culture among the black teenagers whom Bandstand excluded. In 1957, it was one of these fan clubs that made the most forceful challenge to Bandstand's discriminatory admissions policies.15Art Peters, "Negroes Crack Barrier of Bandstand TV Show," Philadelphia Tribune, October 5, 1957; "Couldn't Keep Them Out [photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, October 5, 1957; Delores Lewis, "Bobby Brooks' Club Lists 25 Members," Philadelphia Tribune, December 14, 1957. Although many of these teens watched both Bandstand and Thomas's show, as Bandstand grew in popularity and expanded into a national program, The Mitch Thomas Show remained the only television program that represented the region's black rock and roll fans.

Economics, more than a concern for racial equality, influenced WPFH's decision to provide airtime for this groundbreaking show. Eager to compete with Bandstand and the afternoon offerings on the other network-affiliated stations, WPFH hoped that Thomas's show would appeal to both black and white youth in the same way as black-oriented radio.16On the crossover appeal of black-oriented radio, see Brian Ward, Radio and the Struggle for Civil Rights in the South (Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 2004); William Barlow, Voice Over: The Making of Black Radio (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999); and Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination (New York: Times Books, 1999), 219–255. The station's bet on Thomas was part of a larger strategy that included hiring white disc jockeys Joe Grady and Ed Hurst to host a daily afternoon dance program that started at 5 p.m., after Bandstand concluded its daily broadcast. While The Grady and Hurst Show broadcast five times per week, the weekly Mitch Thomas Show proved to be more influential.

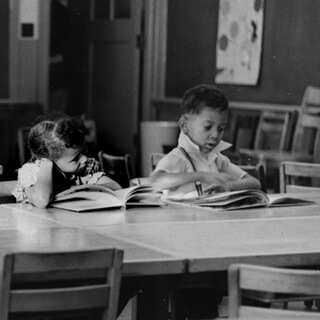

Teens dancing on the The Mitch Thomas Show, locally called the "Black Bandstand," Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1955-1958. Screenshots (1 and 2) from Black Philadelphia Memories, directed by Trudi Brown (WHYY-TV12, 1999). Screenshots courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town.

Drawing on Thomas's contacts as a radio host and on the talents of the teenagers, the program helped shape the music tastes and dance styles of young people in Philadelphia. In a 1998 interview for the documentary Black Philadelphia Memories, Thomas recalled that "the show was so strong that I could play a record one time and break it wide open."17Black Philadelphia Memories, directed by Trudi Brown (Philadelphia, WHYY-TV12, 1999), television documentary. Indeed, Thomas's show hosted some of the biggest names in rock and roll, including Ray Charles, Little Richard, the Moonglows, and Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. It also featured vocal harmony groups from the Philadelphia area.18"Teen-Age 'Superiors' Debut on M.T. Show," Philadelphia Tribune, November 19, 1957. Thomas promoted large stage shows as well as small record hops at skating rinks.19On Mitch Thomas' concerts, see Archie Miller, "Fun & Thrills," Philadelphia Tribune, December 4, 1956; "Rock 'n Roll Show & Dance," Philadelphia Tribune, April 19, 1958; "Swingin' the Blues," Philadelphia Tribune, August 5, 1958; "Mitch Thomas Show Attracts Over 2000," Philadelphia Tribune, August 18, 1958; "Don't Miss the Mitch Thomas Rock & Roll Show," Philadelphia Tribune, July 2, 1960. These events were often racially integrated, "The whites that came, they just said, 'Well I'm gonna see the artist and that's it.' I brought Ray Charles in there on a Sunday night, and it was just beautiful to look out there and see everything just nice."20Mullinax, "Radio Guided DJ to Stars."

Ray Smith, who attended American Bandstand frequently and has done research for one of Dick Clark's histories of the show, remembers that he and other white teenagers watched The Mitch Thomas Show to learn new dance steps. Describing the "black Bandstand," Smith recalled:

First of all, black kids had their own dance show, I think it was on channel 12, but one of the reasons I remember it is because I watched it. And I remember that there was a dance that [American Bandstand regulars] Joan Buck and Jimmy Peatross did called "The Strand" and it was a slow version of the jitterbug done to slow records. And it was fantastic. There were two black dancers on this show, the "black Bandstand," or whatever you want to call it. The guy's name was Otis and I don't remember the girl's name. And I always was like "wow." And then I saw Jimmy Peatross and Joan Buck do it, who were probably the best dancers who were ever on Bandstand. I was talking about it to Jimmy Peatross one day, when I was putting together the book, and he said, "Oh, I watched this black couple do it." And that was the black couple that he watched.21Ray Smith, interview with author, August 10, 2006. Jimmy Peatross and Joan Buck tell a related story about learning how to do The Strand from black teenagers in Twist, directed by Ron Mann (Sphinx Productions, 1992), documentary.

Vera Boyer and Otis Givens show off their dance steps on The Mitch Thomas Show, Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1956–57. Screenshot from Black Philadelphia Memories, directed by Trudi Brown (WHYY-TV12, 1999). Screenshot courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town.

These white teenagers were not alone in watching The Mitch Thomas Show. Smith's experience supports Mitch Thomas's belief that [American Bandstand teens] "were looking to see what dance steps we were putting out. All you had to do was look at 'Bandstand' the next Monday, and you'd say, 'Oh yeah, they were watching.'"22Ibid. They were watching, for example, when dancers on The Mitch Thomas Show started dancing The Stroll, a group dance where boys and girls faced each other in two parallel lines, while couples took turns strutting down the aisle. Thomas remembers that the teens on his show "created a dance called The Stroll. I was standing there watching them dancing in a line, and after a while I asked them, 'What are y'all doing out there?' They said, 'That's The Stroll.' And The Stroll became a big thing."23Black Philadelphia Memories, dir. Trudi Brown. Because the show influenced American Bandstand during its first year as a national program, teenagers across the country learned dances popularized by The Mitch Thomas Show.

Despite its success among black and white teenagers, Thomas's show remained on television for only three years, from 1955 to 1958. His short-lived television career resembled the experiences of other African American entertainers who hosted music and variety shows in this era. The Nat King Cole Show (1956–1957) failed to attract national advertisers and lasted only one year. Before Cole, shows hosted by black singers Lorenzo Fuller (1947) and Billy Daniels (1952) and the variety program Sugar Hill Times (1949) also fared poorly. Among local programs, the Al Benson Show and Richard Stamz's Open the Door Richard both had brief periods of success in 1950s Chicago.24J. Fred MacDonald, Blacks and White TV: African Americans in Television Since 1948 (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1983), 17–21, 57–64; Jannette Dates, "Commercial Television," in Split Image: African Americans and the Mass Media, ed., Davis and Barlow (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1993), 267–327; Christopher Lehman, A Critical History of Soul Train on Television (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 28; Richard Stamz, Give 'Em Soul, Richard! (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 62–63, 77–78; Barlow, Voice Over, 98–103.

Mitch Thomas hosts Lewis Lymon and the Teenchords, Wilmington, Delaware, December 7, 1957, The Philadelphia Tribune. Reproduced with permission of The Philadelphia Tribune. Courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town.

The failure of the station that broadcast The Mitch Thomas Show underscores the tenuous nature of such unaffiliated local programs. Storer Broadcasting Company purchased WPFH in 1956.25Herbert Howard, Multiple Ownership in Television Broadcasting (New York: Arno Press, 1979), 142–147. Storer frequently bought and sold stations and, at the time of the WPFH acquisition, it also owned stations in Toledo, Cleveland, Atlanta, Miami, and Portland. Storer changed WPFH's call letters to WVUE and hoped to move the station's facilities from Wilmington closer to Philadelphia. The plan faltered, and the station suffered significant operating losses over the next year.26Ibid. Thomas's show was among the first victims of the station's financial problems. While advertisers started to pay more attention to black consumers in the 1950s, a product-identification stigma lingered throughout the decade, preventing many brands from sponsoring black programs.27Barlow, Voice Over, 129; Giacomo Ortizano, "One Your Radio: A Descriptive History of Rhythm-and-blues Radio During the 1950s" (PhD dissertation, Ohio University, 1993), 391–423. WVUE cancelled The Mitch Thomas Show in June 1958, citing the program's lack of sponsorship and low ratings compared to the network shows in Thomas's Saturday timeslot.28Art Peters, "Mitch Thomas Fired From TV Dance Party Job," Philadelphia Tribune, June 17, 1958. Shortly after firing Thomas, Storer announced plans to sell WVUE in order to buy a station in Milwaukee as FCC regulations required multiple broadcast owners to divest from one license in order to buy another. Unable to find a buyer for WVUE, Storer turned the station license back to the government, and the station went dark in September 1958.29Howard, Multiple Ownership in Television Broadcasting, 146. The manager of WVUE later told broadcasting historian Gerry Wilkerson, "No one can make a profit with a TV station unless affiliated with NBC, CBS or ABC." As Dick Clark and American Bandstand celebrated the one-year anniversary of the show's national debut, local broadcast competition brought The Mitch Thomas Show's groundbreaking three-year run to an unceremonious end. Thomas continued to work as a radio disc jockey through the 1960s, until he left broadcasting in 1969 to work as a counselor to gang members in Wilmington.

The Mitch Thomas Show usefully troubles the boundary between the South and the North. Historian Brett Gadsden describes Delaware as "a provincial hybrid, one in which ostensibly southern and northern modes of race relations operated."30Brett Gadsden, Between North and South: Delaware, Desegregation, and the Myth of American Sectionalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 7. Many teens who danced on The Mitch Thomas Show or watched the program would have experienced de jure school segregation and the slow realization of educational equality promised by Brown. At the same time, WPHF's Wilmington studios were only thirty miles from Philadelphia, a city that, historian Matthew Countryman notes, many black people called "Up South."31Matthew Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 10. The Mitch Thomas Show teenagers would also have been familiar with segregation as practiced in Philadelphia and televised on American Bandstand. Carried out more covertly, this northern-style segregation was no less intentional or demeaning.32On the limitations of the de jure/de facto framework, see Matthew Lassiter, "De Jure/De Facto Segregation: The Long Shadow of a National Myth," in The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism, eds., Lassiter and Joseph Crespino (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 25–48. On race and segregation in Philadelphia, see Countryman, Up South; Countryman, "'From Protest to Politics': Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965–1984,"Journal of Urban History 32 (September 2006): 813–861; Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town; James Wolfinger, Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Wolfinger, "The Limits of Black Activism: Philadelphia's Public Housing in the Depression and World War II," Journal of Urban History 35 (September 2009): 787–814; Guian McKee, The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia (Chicago: University Chicago Press, 2008); McKee, "'I've Never Dealt with a Government Agency Before': Philadelphia's Somerset Knitting Mills Project, the Local State, and the Missed Opportunities of Urban Renewal," Journal of Urban History 35 (March 2009): 387–409; and Lisa Levenstein, A Movement Without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). Seeing The Mitch Thomas Show as "between North and South" highlights the constant negotiation of sectional identities and imaginaries.

Teenage Frolics

J. D. Lewis' Teenage Frolics, which aired from 1958 to 1983, stayed on the air longer than any other local teen dance program. A graduate of Morehouse College and a World War II veteran, John Davis (J. D.) Lewis, Jr. started his radio career at Raleigh's WRAL in 1947 as a morning deejay playing gospel music. A. J. Fletcher and Fred Fletcher's Capitol Broadcasting Company, which owned WRAL, received a TV license in 1956 and Lewis played an important role in convincing the Federal Communications Comission (FCC) that WRAL-TV would serve African American viewers.33Clarence Williams, "JD Lewis Jr.: A Living Broadcasting Legend," Ace: Magazine of the Triangle, September–October 2002, 12–14, 70. Unlike The Mitch Thomas Show and Teenarama, Teenage Frolics aired on a VHF (very high frequency) station with a network affiliation (WRAL-TV had a primary affiliation with NBC and a secondary affiliation with ABC).34"WRAL-TV," 1960 Broadcasting Yearbook, A–73 Despite these network ties, WRAL proved challenging in other ways. Jesse Helms, later a US senator and national conservative leader, became an executive at Capitol Broadcasting in 1960 and delivered news editorials railing against communism, liberalism, and civil rights. As program manager in the late-1960s, Helms was Lewis's boss.35Jesse Helms, Here's Where I Stand (New York, Random House, 2005), 44–51; Ernest Furgurson, Hard Right: The Rise of Jesse Helms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1986), 69–91; William Link, Righteous Warrior: Jesse Helms and the Rise of Modern Conservatism (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008), 64–98. WRAL, however, offered Teenage Frolics signal strength and stability, and Lewis's success at attracting advertisers and navigating station politics kept the program on the air for twenty-five years.

In a letter to potential advertisers, WRAL billed Teenage Frolics as "a live and lively dancing party featuring colored teenagers from high schools in the Channel 5 area." The station also included a coverage map of WRAL-TV, "which includes the most heavily populated Negro areas of the state of North Carolina (Approximately 450,000 Negroes)," and promised that "'The Teen-Age Frolic Show' affords a wonderful opportunity for firsthand consumer reaction to the sponsor's product."36J.D. Lewis (WRAL), letter to Dick Snyder, May 24, 1963, Lewis Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, catalog number 5499, folder 139. Lewis secured Pepsi Cola, which sponsored Teenage Frolics as part of the "special markets" campaign to increase sales of the beverage among African Americans.37On Pepsi marketing to black customers, see Stephanie Capparell, The Real Pepsi Challenge: How One Pioneering Company Broke Color Barriers in 1940s American Business (New York: Free Press, 2008). He served as a Pepsi public relations and sales representative for the Raleigh area from 1965 to 1968. Pepsi's sponsorship proved important to making of Teenage Frolics financially viable in the 1960s as it fought for airtime against more profitable national programming. A 1967 memo from Jesse Helms highlights the pressures Teenage Frolics faced from national broadcasts and mentions Pepsi's sponsorship of the show. "As per our conversation of yesterday, it is going to be necessary that we make some adjustment in our Saturday afternoon schedule this fall with respect to Teen-Age Frolics," Helms wrote to inform Lewis and other staff that the show would have to be shortened from its regular one hour broadcast time.

The abbreviated (15 minute) programs are necessary because of ABC's scheduling of American Bandstand from 12:30–1:30 p.m. each Saturday. To do otherwise would necessitate our preemption of a solid hour of commercial network programming, which I deem inadvisable. In the 15-minute programs, please leave two 60-second cutaways for the Pepsi-Cola commercials which I am advised are all that we have sold in Teen-Age Frolics anyhow."38Jesse Helms, memo to Ray Reeve, July 6, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 139; Ray Reeve, memo to J.D. Lewis, July 7, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 139.

Despite Helms's backhanded reference, Pepsi's sponsorship offered Teenage Frolics a national brand sponsor, something neither The Mitch Thomas Show nor Teenarama possessed.

WRAL's mailing to advertisers also included a list of the schools and organizations that had visited the show. Mapping a partial list of the groups that visited the studio highlights how many young people wanted to appear on the show and participate in its creation of black youth music culture. When North Carolina began desegregation from 1969 to 1971, many black high schools were closed or were converted to elementary schools or junior highs. In 1970, for example, black students who attended W. E. B. DuBois High School were transferred to historically white Wake Forest High School and the DuBois High School building became Wake Forest-Rolesville Middle School.39Barry Malone, "Before Brown: Cultural and Social Capital in a Rural Black School Community, W.E.B. Dubois High School, Wake Forest, North Carolina," The North Carolina Historical Review 85, no. 4 (October 2008): 443–444. "When black schools closed," historian David Cecelski writes, "their names, mascots, mottos, holidays, and traditions were sacrificed with them, while students were transferred to historically white schools that retained those markers of cultural and racial identity."40David Cecelski, Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina and the Fate of Black Schools in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 9. Teenage Frolics offered a black cultural space that bridged this period between segregated and integrated schools.

Letters from viewers and aspiring musicians to Lewis and WRAL attest that many teenagers and performers wanted to appear on Teenage Frolics. "I watch your show every Saturday and enjoy it very much," one viewer wrote. "Your records are up to date and your show is very much for teenagers. I notice everybody that come are in groups. . . . I would like to come with 6 or 7 others, and be a part of your show. I would appreciate your information by telling me if we can come and when we can come. Please rush your information."41Susan Jordan, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1966-67], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. A letter to "John D." from an adult chaperone suggests that Lewis was a well-known and approachable local television personality, "I came to your house two Sundays ago to see you. I asked your daughter to tell you to call me, please. . . . My plan is to bring a group of 45 or 50 children . . . on Saturday, May 14th. My question is—may they appear on your 'Dance Party'?"42Hazel Jordan, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), May 8, 1966, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. Fans also felt free to criticize the format of Teenage Frolics. One particularly opinionated "Frolic Fan" wrote, "I am very concerned with your show. Once you really had a rocking roll show up here. But now it doesn't interest anyone." This viewer offered Lewis several suggestions for how to improve the show, including, "You need more records. New records come out every day and you play old ones."43"Frolic Fan," letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1966-67], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. Another letter complained that a local band, Irving Fuller and the Corvettes, appeared too often on the show, "Many of the people around Durham and elsewhere are bored of listening to the Corvettes. It seems as if you never play records anymore. Most people listening to a dance program would rather hear the latest records."44Anonymous ("102 Pilot St.), letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 10, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140.

Letter from The Superiors to Teenage Frolic, North Carolina, July 25, 1967. Used with permission of Yvonne Holley, Lewis Family Papers #5499, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In addition to viewer letters, Lewis received mail from local music groups that watched and wanted to appear on the show. Groups like Donald and the Hitchhikers, Tiny and the Tinniettes, Little Joe and the Diamonds, Cobra and the Fabulous Entertainers, and the Dacels saw Teenage Frolics as a way to perform for other black teenagers and become known beyond their high schools and neighborhoods. The Superiors, a group of six fourteen to sixteen-year-olds from Smithfield, North Carolina, expressed dreams of auditioning for Motown and asked, "could we sort of take an inch of your show to sing" to "show North Carolina they will be greatly represented."45Donald Hodge, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 21, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; Guadalupe Hudson, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 24, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; Daniel Jackson, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), May 29, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; "Nero, the Mad," letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 24, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140, July 22, 1967; Gwendolyn Gilmore, J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1967], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140.

As television production became increasingly centralized in Los Angeles in the 1960s, Teenage Frolics was part of the everyday life of black teenagers in the Raleigh area. In this way, Teenage Frolics served as what scholar and musician Guthrie Ramsey calls a "community theater." Ramsey describes "community theaters" as "sites of cultural memory" that "include but are not limited to cinema, family narratives and histories, the church, the social dance, the nightclub, the skating rink, and even literature."46Guthrie Ramsey, Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 4. From this perspective, localism was a virtue for Teenage Frolics rather than a detriment, because it offered young people a community connection that was not possible with national television. Sisters Gwendolyn and Lena Horton, for example, regularly walked from the Walnut Terrace neighborhood to appear on the show. Gwendolyn Horton recalled, "We would practice all week so we'd be ready on Saturday," while Lena Horton noted, "just to get out there, you thought you were something that could be shown on TV."47Cash Michaels, "Memories of Teenage Frolics," The Carolinian, December 4, 1997. Comparing the show to Soul Train in 1997, The Carolinian, a Raleigh-based African-American newspaper, commented that Teenage Frolics "gave the Hollywood production a run for its money in these parts."48Ibid. Soul Train and American Bandstand attracted nationally known performers, but on Teenage Frolics, teenagers participated in the show's creation and saw their neighbors, classmates, friends, and family do the same.

Teenarama Dance Party

A WOOK-TV advertisement in the 1965 Broadcasting Yearbook highlights the promise and precarity of the station that broadcast Teenarama Dance Party. The advertisement billed WOOK-TV as "America's First Negro Oriented TV Station" broadcasting "To & For Washington, D.C.'s 57% Negro population." While the advertisement used large, bold font to tout the city's majority African American population to potential advertisers, smaller letters tried to put a positive spin on the station's limitations, "281,000 UHF sets in operation in WOOK area as of Oct. 1, 1964."49"WOOK-TV," 1965 Broadcasting Yearbook, A–10. Whereas all television sets could pick up VHF stations, which carried major network programming, UHF (ultra high frequency) stations required viewers to have special UHF tuners. This meant buying additional hardware to receive the channels, or, after Congress passed the All-Channels Receiver Act in 1962, buying a newer television set.50Christopher Sterling and John Michael Kittross, Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting, Third Edition (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), 255–256, 351–352, 383, 415–416. Both of these options were cost prohibitive for many of the African American viewers WOOK hoped to reach. Teenarama Dance Party received top billing in this advertisement and ultimately the show's fortunes would rise and fall with WOOK's.

WOOK-TV advertisement for Teenarama host Bob King, 1965. Kendall Productions Records, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. Image courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont.

Teenarama host Bob King came to WOOK in 1956 from WRAP radio in his hometown of Norfolk, Virginia, where he hosted an R&B show.51James Lee, "He Plays Teens Picks," Washington Star, [n.d.] ca. 1963. Looking back on his earlier radio career, King recalled, "In those days what I was playing was called 'race music.' It was a little more raucous. Then people like Presley came along and began to change it . . . In Norfolk in 1951 and 1952, they began calling it rhythm and blues. The hillbilly influence began creeping into it and the music became what we call rock and roll . . . The distinction, which may be a fine one, is the style of the singer and the background of a record. A lot of rock and roll today is bordering on what is called 'popular music.'"52Ibid. King went on to say that he considered Teenarama and his radio show to be "rhythm and blues" programs, and R&B artists like James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Walter Jackson, and Chuck Jackson all performed on Teenarama. For these and other artists who played at Washington's historically black Howard Theater, Teenarama offered an additional opportunity to perform and promote their music while they were in the city.

While performers, record companies, and music fans welcomed Teenarama's promotion of R&B, WOOK's music programing drew criticism from Washington's black press and the city's black leaders. One editorial in the Washington Afro-American complained that WOOK-radio was "monotonous" because it played "rock 'n roll 17 hours a day," and described "'Colored' radio" as having "dedicated itself to a low-mentality level of programming which dispenses musical slop to remind colored people that's all they want to hear."53"WOOK-TV's Coloring Book," Washington Afro-American, February 16, 1963; "WOOK's Insult to Our Race," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. Another editorial argued that WOOK-TV insults "the colored race's intelligence by advertising itself as nothing but a station programming plain ol' music and dancing. As colored people, we've been plagued with that image ever since we were freed from slavery. WOOK-TV only perpetuates this image."54"Voice of the People: In Defense of WOOK-TV," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) chairman Julies Hobson also expressed concern, saying, "I object to foot tapping, dancing, screaming and shouting." Sterling Tucker, director of the Washington branch of the Urban League, worried that WOOK's focus on the "Negro market" was out of step with civil rights efforts, "You don't go along the road of segregation to achieve integration."55"WOOK Says it Isn't Just One-Color TV," Washington Star, February 11, 1963. These critiques reflected differences in age and class between the readership of the Afro-American and potential viewers and listeners of WOOK-TV and WOOK-radio.56John Henry Murphy, Sr. started publishing the Afro-American newspaper in Baltimore in 1892. By 1960, under the control of Carl Murphy, the Afro-American published editions across the Mid-Atlantic States. The Afro-American papers cultivated an older and more middle class black audience than the viewers and listeners WOOK-TV and WOOK-radio targeted. At the same time, the critics expressed concern that the station's management and white president, Richard Eaton, would not attend to community interests and concerns beyond musical entertainment. For his part, Eaton argued on the eve of the station's first broadcast, "WOOK-TV will be a place where young Negroes can develop their talents and the problems of the Negro [will be] vividly displayed. We hope to show interracial activities which are harmonious. We do not intend to assume a controversial role."57"Nation's First Minority Group TV Station to Broadcast Today," Chicago Defender, February 11, 1963.

WOOK-TV never assumed a leadership role with regards to the main political issues of its era, but Teenarama showcased black youth culture for Washington viewers. Chuck Jackson, an R&B artist who appeared on the show several times, described Teenarama's importance, "Before this, with some kids, no one has given them a sense of being someone, a sense of independence. All kids are creative, but we don't let them express it . . . These kids are typical of all the kids who are given something to do, some responsibility."58Nan Randall, "Rocking and Rolling Road to Respectability," Washington Post, July 4, 1965. In an interview with filmmaker Beverly Lindsay-Johnson, who made an important documentary on the show, Teenarama regular Reginald "Lucky" Luckett recalled, "One of the key things about the program was that it got the [teens] involved. If you stood around the cameramen, they would show you how to operate the cameras. I became more fascinated with the operation than the program." Another regular, William Clemmons recalled, "We couldn't go on The Milt Grant Show on a regular basis. We couldn't go on Shindig on a regular basis. We couldn't go on American Bandstand on a regular basis. We had Teenarama, which was ours."59"Dance Party (The Teenarama Story), Research Narrative," Box 2, Kendall Production Records, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. As Clemmons suggests, Teenarama afforded a level of television visibility for black teenagers and black music that was not found on national programs.

Bob King watches dancers on Teenarama, Washington DC, ca. 1960s. Kendall Productions Records, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. Image courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont.

One of the challenges with analyzing The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama is that no visual traces of the shows are known to exist. Most early television shows were recorded over or discarded because storage was too expensive. In her documentary on Teenarama Beverly Lindsay-Johnson dealt with this lack of footage by recruiting contemporary Washington teenagers, teaching them the locally distinct "hand dance" of the era, and having them reenact the dances. "We had eight weeks to get these kids taught," Lindsay-Johnson remembered, "and when it came time to shoot the reenactments I wasn't sure they got it." She recalled that this changed when they got period clothing, "It was a community effort, there was a guy who used to dance on Teenarama who worked at the Salvation Army and he said, 'come in and get anything you want'…when the kids had the clothes on…the kids got it, I knew they had it."60Beverly Lindsay-Johnson, interview with author, January 8, 2013. This story and the black and white reenactments in Lindsay-Johnson's film speak both to the creativity that historians of television must employ and to the imprint Teenarama made on the black population in Washington, DC.

The Milt Grant Show

As WOOK-TV prepared to come on the air in 1963, the Afro-American newspaper received a letter from Rev. Clarence Burton Jr., defending the station and raising a question about the teen dance show that predated Teenarama. "Who can tell," Burton offered, "from the working of the station maybe we can increase our colored stardom. There have been many cases where our leaders needed to make outcries such as Milt Grant's TV dance program, it seems to me that that was segregation."61"Voice of the People: In Defense of WOOK-TV," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. As Burton suggests, during its five years The Milt Grant Show (1956–1961) was an officially segregated program. The show blocked black teens from the studio, though complaints from black viewers eventually led to one show per week featuring a black studio audience (so-called "Black Tuesday"). Despite its ban on black teenagers, the show regularly featured black R&B performers who were in town to perform at the Howard Theater. The Milt Grant Show is particularly interesting for how it sought to bring black music performances to television viewers while maintaining a segregated studio audience that would appeal to sponsors.

Only one kinescope of The Milt Grant Show is known to exist, but it features two separate performances by R&B performers—one by the duo Johnnie and Joe (Johnnie Lee Richardson and Joe Walker), and the other by LaVern Baker—that help explain how the show sought to manage the differences between black performers and white audience members. In each clip, the teenagers dance as the singers lip sync to recordings of their songs, as was the common practice in this era. The cameras shift between a medium shot of the artists and a wide shot of couples dancing, before using a picture-in-picture production technique that presented the shot of the artists in a box overlaying the shot of the teenagers dancing. A performance later in the show by white singer Jeri Renay did not use this technique. The resulting image nicely illustrates the tensions surrounding televising black music to white audiences. Broadcasting black musical performers on television was more challenging than radio, because television made the performers' bodies visible, and on dance shows like these, put their bodies in close proximity to those of dozens of teenagers. Alan Freed's Big Beat television show, for example, was cancelled in August 1957 after affiliated stations complained about black teenage singer Frankie Lymon dancing with a white teenage girl. A year later, an American Bandstand producer told the New York Post that this incident contributed to American Bandstand's segregation.62John Jackson, Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock & Roll (New York: Shirmer Trade Books, 2000), 168–169; Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock 'n' Roll Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 56. The Milt Grant Show clips from May 1957 predate the Freed-Lymon controversy, but the show faced similar concerns. Grant needed to be able to feature black performers in a way that was safe for the consuming pleasure of the white studio and television audiences and the sponsors that were eager to reach them. With black performers only a few feet away from the white teenage dancers in the studio, the picture-in-picture technique demarcated the racial boundary between performers and audiences and offered one strategy for televising black musicians while maintaining racial segregation.

Despite the racial segregation of the studio audience, The Milt Grant Show offered black performers like LaVern Baker valuable exposure to white consumers. In the prior three years, Baker had mixed experiences with crossing over from the R&B charts to the pop chart. Her songs "Tweedle Dee" and "Jim Dandy" both reached the top twenty of the pop chart, but white singer Georgia Gibbs's cover of "Tweedle Dee" topped the pop chart and outsold Baker's version.63Arnold Shaw, Honkers and Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues (New York: Macmillan, 1978), 376. Baker's contemporary Ruth Brown explained, "I wasn't so upset about other singers copying my songs because that was their privilege, and they had to pay the writers of the song. But what did hurt me was the fact that I had originated the song, and I never got the opportunities to be in the top television shows and the talk shows. I didn't get the exposure. And the other people were copying the style, the whole idea."64Quoted in Ward, Just My Soul Responding, 48. Baker, who appeared on The Milt Grant Show while she was in town to play the Howard Theater, performed "Jim Dandy Got Married" and "Play the Game of Love" on this episode. Even if The Milt Grant Show carefully managed the positioning of black singers and white dancers, television viewers in the greater Washington area saw Baker perform and this exposure was one step towards establishing her as a crossover star in the late-1950s and early-1960s.

The Milt Grant Show dedicated almost every minute to selling products, and Grant, as this message to potential sponsors makes clear, was a compelling and unabashed salesman. While WTTG-TV lacked a network affiliation, Grant proved skilled at recruiting and serving sponsors.65WTTG-TV was was founded as a DuMont station and DuMont ended network operations in 1956. "Grant provides an all-out sponsor and agency service," Billboard reported in 1961. "He attends sales meetings, store openings and maintains close identification with his sponsors' products off the air as well as on."66"TV Jockey Profile: The Milt Grant Show," Billboard, February 6, 1961, 43. He promised potential sponsors that for an hour every afternoon WTTG-TV's studio in the Raleigh Hotel in downtown Washington would be a nexus for selling products to area teenagers. From paid advertisements for consumer goods to promotions of records and musical guests, also often paid for by record promoters, The Milt Grant Show presented its viewers with a host of messages. The show urged teenagers to drink Pepsi, eat at Tops' Drive-Inn, listen to Motorola portable radios, and buy the newest records at the Music Box record store. This was an extraordinarily high level of promotional activity, even by the standards of commercial television. Music was the glue that held together a carnival of consumption.

Sponsors that advertised on The Milt Grant Show bought interaction between their products and the show's teenagers. For example, in a 1957 episode the show's teens finished dancing to The Everly Brothers' "Bye Bye Love" and the camera focused on Grant in front of a table with dozens of bottles of Pepsi. After Grant took a big drink of the soda and delivered the sales pitch ("Never too heavy, never too sweet, always just right"), he asked two teenagers to help hand out bottles of the sponsor's drink to the dancers. As Grant introduced The Four Aces' "I Just Don't Know," he exited the scene, the camera pulled back to focus on teens who flocked to pick up their free Pepsi. The teens held and drank their sodas while dancing, keeping the sponsor's product in the picture throughout the song. Some teens were still holding their bottles when Grant started the next advertisement for Motorola portable radios. Here again, the advertisement incorporated the studio audience, with one young woman holding the radio while Grant praised its features. These interpolated commercials, common in radio and television in this era, offered sponsors daily visual evidence of teenagers' eagerness to consume and encouraged The Milt Grant Show's viewers to participate in the same rituals of consumption.

Conclusion

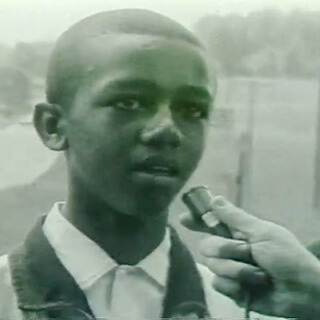

From one perspective, these televised teen dance shows were commercialized diversions during an era of profound changes in the racial dynamics of the South. From another, however, these shows were spaces that celebrated the creative potential and everyday lives of black youth. To show how these perspectives are intertwined I'll conclude with a brief discussion of a dance show that started broadcasting at a pivotal time and from a pivotal place in the history of civil rights. Steve's Show debuted in Little Rock, Arkansas, in the spring of 1957, months before the integration crisis at Central High School drew national attention. Examining Little Rock, political theorist Danielle Allen writes, "Nineteen fifty-seven forced citizens to confront the nature of their citizenship—that is, the basic habits of interaction in public spaces—and many were shamed into desiring a new order."67Danielle Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 5. Allen argues that images, like Will Counts's iconic photograph of black student, Elizabeth Eckford, surrounded by a white mob and being cursed by white student Hazel Bryan, forced some white Americans to revaluate their "habits of citizenship."

Hazel Bryan (left) harasses Elizabeth Eckford as black students attempt to integrate Little Rock's Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas, September 4, 1957. Photograph by Will Counts. Courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont.

Changes to the structure of public life took place slowly. Televised teen dance shows offer an example of how "basic habits of interaction in public spaces" did not change dramatically in 1957. Just over one mile from Central High School, Steve's Show broadcast from the KTHV-TV studios. While Little Rock's school desegregation crisis led print and television news across the country in the fall of 1957, Arkansas viewers could tune in every afternoon to watch white teenagers dance on the still-segregated Steve's Show. Like other white teens that protested the desegregation of Central High, Hazel Bryan danced regularly on Steve's Show. After the widely circulated photograph made her a local celebrity she attended the show with a bodyguard.68David Margolick, Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 44, 290. Steve's Show was a highly visible regional space that asserted a racially segregated public culture and continued to do so until it went off the air in 1961. And Steve's Show was not unique: Dick Reid's Record Hop in Charleston, West Virginia; Ginny Pace's Saturday Hop in Houston, Texas; John Dixon's Dixon on Disc in Mobile, Alabama; Bill Sanders's show in Chattanooga, Tennessee; Dewey Phillips's Pop Shop in Memphis, Tennessee; and Chuck Allen's Teen Tempo in Jackson, Mississippi were all segregated dance shows. Like The Milt Grant Show, Baltimore's Buddy Deane Show, the inspiration for John Waters's Hairspray film and the later Broadway musical and Hollywood film, was officially segregated and only allowed black teens to enter the studio on specific days. Nationally, American Bandstand blocked black teens from entering the studio during its years in Philadelphia, despite host Dick Clark's claims to the contrary. Every weekday afternoon, in each of these broadcast markets, these shows presented images of exclusively white teenagers.

Steve's Show, Little Rock, Arkansas, late 1950s. Broadcast locally during the 1957 school integration crisis, the show featured exclusively white dancers, including Hazel Bryan. Screenshot from Steve's Show, a documentary directed by Sandra Hubbard (Morning Star Studio, 2004). Screenshot courtesy of Matthew F. Delmont.

In his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke to what it meant for young black people to be excluded from these sorts of entertainment spaces. In a long list of reasons why "we find it difficult to wait," King includes, "when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can't go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky…then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait." King's mention of "Funtown" is preceded by references to lynch mobs, police brutality and the "airtight cage of poverty," and followed by references to hotel segregation and racial slurs. While it is tempting to see "Funtown" as somehow less important than these issues, to do so is a mistake. The "Funtown" reference is powerful because it captures one of the ways that Jim Crow segregation and white supremacy were most meaningful to children and teenagers. For many young people being blocked from amusements parks, swimming pools, and skating rinks would be their first exposure to what King calls the feeling of "forever fighting a degenerating sense of 'nobodiness.'"69Martin Luther King, Jr., "Letter from a Birmingham Jail," April 16, 1963.

The prevalence of racial segregation in recreational spaces and on white teen dance shows throws the importance of The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama into sharp relief. If white teen shows sought to shore up the supremacy of whiteness in youth music culture, the black teen shows visualized black teens as equal participants in the production and consumption of music culture. In her study of the landmark black television show Soul!, that ran from 1968 to 1972, Gayle Wald argues that the show "created a television space where black people…could see, hear, and almost feel each other." Wald describes this as an "affective compact" that "complicates the clear division between production and consumption."70Gayle Wald, It's Been Beautiful: Soul! and Black Power Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 217, 72. While Soul! was more politically and aesthetically adventurous than The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama, these teen dance shows fostered a similar compact between their audiences and performers. Mitch Thomas, J. D. Lewis, and Bob King created televisual spaces that privileged black audiences and displayed the creative energies and talents of black youth. Years before Soul Train (1971–2006) brought black dance television to national audiences, The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama highlighted black music and dance styles.71Ericka Blount Danois, Love, Peace, and Soul: Behind the Scenes of America's Favorite Dance Show Soul Train: Classic Moments (Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2013); Nelson George, The Hippest Trip in America: Soul Train and the Evolution of Culture and Style (New York: William Morrow, 2014); Questlove, Soul Train: The Music, Dance, and Style of a Generation (New York: Harper Design, 2013). Unlike Soul Train, which moved from Chicago to Hollywood after one year, these local shows featured and appealed to black teens from Wilmington, Raleigh, and Washington, and as the opening clip from Seventeen suggests, they influenced American musical cultures in surprising ways.

Ultimately, these televised teen dance shows encourage us to expand the range of sounds and images we associate with black youth in the South. It takes nothing away from the young men and women who risked their lives to desegregate schools and lunch counters to recognize that thousands of teenagers found joy and value in dancing on television or watching their peers do the same. If the iconic civil rights images from cities like Little Rock, Greensboro, and Birmingham attest to the fact that young activists struggled to be treated as first-class citizens, The Mitch Thomas Show, Teenage Frolics, and Teenarama emphasized that black youth were worthy of being first-class consumers and teenagers.72On the relationship between citizenship and consumption, see Lizbeth Cohen, A Consumer's Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumptions in Postwar America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003); Robert Weems, Jr., Desegregating the Dollar: African American Consumerism in the Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Victoria Wolcott, Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press: 2012).

About the Author

Matthew Delmont is associate professor of history at Arizona State University and author of The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia (University of California Press, American Crossroads series, February 2012), and Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (University of California Press, American Crossroads series, forthcoming February 2016). He is currently finishing a book titled Making Roots: How an Epic Book and Television Miniseries Made History and Why Roots Still Matters (under contract with University of California Press).

Recommended Resources

Text

Bodroghkozy, Aniko. Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Delmont, Matthew. The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Ramsey, Guthrie P. Jr.. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Sterling, Christopher and John Michael Kittross. Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting, Third Edition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002.

Video and Audio

1950s Teen Dance TV Shows, Volume 1. DVD. Filmed 1957–1958. The Video Beat, 2015.

Dance Party: The Teenarama Story. DVD. Directed by Herb Grimes. 2007. Washington, DC: Kendall Productions, 2007.

Teenage. DVD. Directed by Matt Wolf. 2013. New York: Cinreach, 2013.

"Teen Dance Music from the 50’s and 60’s." My Place. Vermont Public Radio. Colchester, VT: VPR, July 11, 2009.

Matthew Delmont, "The Nicest Kids in Town." University of California Press. Last modified April 11, 2014. http://scalar.usc.edu/nehvectors/nicest-kids/index.

Museum of Broadcast Communications. "Music on Television." http://www.museum.tv/eotv/musicontele.htm.

National Museum of American History, Behring Center. "Separate is Not Equal: Brown v Board of Education." http://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/1-segregated/segregated-america.html.

"Seventeen (WOI-TV's teen dance show), 1958." Televised by WOI-TV on February 1, 1958. YouTube video, 31:42. Posted November 21, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AD76LwR2JA.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Gertrude "Ma" Rainey, vocal performance of "See See Rider Blues" by Ma Rainey and Lena Arant, recorded October 16, 1924, by Paramount, catalogue number 12252, 78 rpm. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Jeff Todd Titon, Early Downhome Blues: A Musical and Cultural Analysis (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977), 74–75; Tom Hughes, Hanging the Peachtree Bandit: The True Tale of Atlanta's Infamous Frank Dupree (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014). |

| 3. | Sarah Caroline Thuesen, Greater Than Equal: African American Struggles for Schools and Citizenship in North Carolina, 1919 –1965 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 225–229. |

| 4. | Jeffrey Crow, Paul Escott, and Flora Hatley, A History of African Americans in North Carolina (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1992). |

| 5. | Aniko Bodroghkozy, Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012); Martin Berger, Seeing Through Race: A Reinterpretation of Civil Rights Photography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011); and Leigh Raiford, Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). |

| 6. | Quoted in Bodrogkozy, Equal Time, 2. |

| 7. | "Afro-Americans who lived in communities as diverse as Chicago, Norfolk, and Buxton, Iowa, congregated—sometimes along class lines, but always together," Earl Lewis argues. "In the southern context, congregation was important because it symbolized an act of free will, whereas segregation represented the imposition of another's will." Earl Lewis, In Their Own Interests: Race, Class, and Power in Twentieth-Century Norfolk, Virginia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 91–92. |

| 8. | Matthew Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock 'n' Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). |

| 9. | Norma Coates, "Elvis from the Waist Up and Other Myths: 1950s Music Television and the Gendering of Rock Discourse," in Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones, eds. Roger Beebe and Jason Middleton (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 226–251; Coates, "Filling in Holes: Television Music as a Recuperation of Popular Music on Television," Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 1, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 21–25; Murray Forman, One Night on TV Is Worth Weeks at the Paramount: Popular Music on Early Television (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012); Julie Malnig, "Let's Go to the Hop: Community Values in Televised Teen Dance Programs of the 1950s," Dance & Community: Proceedings of The Congress on Research in Dance (August, 2006): 171–175; Tim Wall, "Rocking Around the Clock: Teenage Dance Fads from 1955 to 1965," in Ballrooms, Boogie, Shimmy, Sham, Shake: A Social and Popular Dance Reader, ed. Julie Malnig (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 182–198; George Lipsitz, Midnight at the Barrelhouse: The Johnny Otis Story (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); and Brian Ward, Just My Soul Responding: Rhythm and Blues, Black Consciousness, and Race Relations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). |

| 10. | "The NAACP Reports: WCAM (Radio)," August 7, 1955, NAACP collection, URB 6, box 21, folder 423, TUUA. |

| 11. | Eustace Gay, "Pioneer In TV Field Doing Marvelous Job Furnishing Youth With Recreation," Philadelphia Tribune, February 11, 1956; Gary Mullinax, "Radio Guided DJ to Stars," The News Journal Papers (Wilmington, DE), January 28, 1986, D4. |

| 12. | Otis Givens, interview with author, June 27, 2007. |

| 13. | Quoted in John Roberts, From Hucklebuck to Hip-Hop: Social Dance in the African American Community in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Odunde, 1995), 37. |

| 14. | On the Philadelphia Tribune's "Teen-Talk" coverage of Mitch Thomas' show, see "They're 'Movin' and Groovin,'" Philadelphia Tribune, July 31, 1956; Dolores Lewis, "Talking With Mitch," Philadelphia Tribune, November 9, 1957; Lewis, "Stage Door Spotlight," Philadelphia Tribune, November 9, 1957; Laurine Blackson, "Penny Sez," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957 and April 26, 1958; Dolores Lewis, "Philly Date Line," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957; "Queen Lane Apartment Group [photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, December 7, 1957; Jimmy Rivers, "Crickets' Corner," Philadelphia Tribune, January 21 and April 22, 1958; Edith Marshall, "Current Hops," Philadelphia Tribune, March 1, 8 and 22, 1958; Marshall, "Talk of the Teens," Philadelphia Tribune, March 22, 1958; and "Presented in Charity Show [Mitch Thomas photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, April 22, 1958. |

| 15. | Art Peters, "Negroes Crack Barrier of Bandstand TV Show," Philadelphia Tribune, October 5, 1957; "Couldn't Keep Them Out [photo]," Philadelphia Tribune, October 5, 1957; Delores Lewis, "Bobby Brooks' Club Lists 25 Members," Philadelphia Tribune, December 14, 1957. |

| 16. | On the crossover appeal of black-oriented radio, see Brian Ward, Radio and the Struggle for Civil Rights in the South (Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 2004); William Barlow, Voice Over: The Making of Black Radio (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999); and Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination (New York: Times Books, 1999), 219–255. |

| 17. | Black Philadelphia Memories, directed by Trudi Brown (Philadelphia, WHYY-TV12, 1999), television documentary. |

| 18. | "Teen-Age 'Superiors' Debut on M.T. Show," Philadelphia Tribune, November 19, 1957. |

| 19. | On Mitch Thomas' concerts, see Archie Miller, "Fun & Thrills," Philadelphia Tribune, December 4, 1956; "Rock 'n Roll Show & Dance," Philadelphia Tribune, April 19, 1958; "Swingin' the Blues," Philadelphia Tribune, August 5, 1958; "Mitch Thomas Show Attracts Over 2000," Philadelphia Tribune, August 18, 1958; "Don't Miss the Mitch Thomas Rock & Roll Show," Philadelphia Tribune, July 2, 1960. |

| 20. | Mullinax, "Radio Guided DJ to Stars." |

| 21. | Ray Smith, interview with author, August 10, 2006. Jimmy Peatross and Joan Buck tell a related story about learning how to do The Strand from black teenagers in Twist, directed by Ron Mann (Sphinx Productions, 1992), documentary. |

| 22. | Ibid. |

| 23. | Black Philadelphia Memories, dir. Trudi Brown. |

| 24. | J. Fred MacDonald, Blacks and White TV: African Americans in Television Since 1948 (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1983), 17–21, 57–64; Jannette Dates, "Commercial Television," in Split Image: African Americans and the Mass Media, ed., Davis and Barlow (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1993), 267–327; Christopher Lehman, A Critical History of Soul Train on Television (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 28; Richard Stamz, Give 'Em Soul, Richard! (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 62–63, 77–78; Barlow, Voice Over, 98–103. |

| 25. | Herbert Howard, Multiple Ownership in Television Broadcasting (New York: Arno Press, 1979), 142–147. |

| 26. | Ibid. |

| 27. | Barlow, Voice Over, 129; Giacomo Ortizano, "One Your Radio: A Descriptive History of Rhythm-and-blues Radio During the 1950s" (PhD dissertation, Ohio University, 1993), 391–423. |

| 28. | Art Peters, "Mitch Thomas Fired From TV Dance Party Job," Philadelphia Tribune, June 17, 1958. |

| 29. | Howard, Multiple Ownership in Television Broadcasting, 146. |

| 30. | Brett Gadsden, Between North and South: Delaware, Desegregation, and the Myth of American Sectionalism (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 7. |

| 31. | Matthew Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 10. |

| 32. | On the limitations of the de jure/de facto framework, see Matthew Lassiter, "De Jure/De Facto Segregation: The Long Shadow of a National Myth," in The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism, eds., Lassiter and Joseph Crespino (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 25–48. On race and segregation in Philadelphia, see Countryman, Up South; Countryman, "'From Protest to Politics': Community Control and Black Independent Politics in Philadelphia, 1965–1984,"Journal of Urban History 32 (September 2006): 813–861; Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town; James Wolfinger, Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007); Wolfinger, "The Limits of Black Activism: Philadelphia's Public Housing in the Depression and World War II," Journal of Urban History 35 (September 2009): 787–814; Guian McKee, The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia (Chicago: University Chicago Press, 2008); McKee, "'I've Never Dealt with a Government Agency Before': Philadelphia's Somerset Knitting Mills Project, the Local State, and the Missed Opportunities of Urban Renewal," Journal of Urban History 35 (March 2009): 387–409; and Lisa Levenstein, A Movement Without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). |

| 33. | Clarence Williams, "JD Lewis Jr.: A Living Broadcasting Legend," Ace: Magazine of the Triangle, September–October 2002, 12–14, 70. |

| 34. | "WRAL-TV," 1960 Broadcasting Yearbook, A–73 |

| 35. | Jesse Helms, Here's Where I Stand (New York, Random House, 2005), 44–51; Ernest Furgurson, Hard Right: The Rise of Jesse Helms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1986), 69–91; William Link, Righteous Warrior: Jesse Helms and the Rise of Modern Conservatism (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008), 64–98. |

| 36. | J.D. Lewis (WRAL), letter to Dick Snyder, May 24, 1963, Lewis Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, catalog number 5499, folder 139. |

| 37. | On Pepsi marketing to black customers, see Stephanie Capparell, The Real Pepsi Challenge: How One Pioneering Company Broke Color Barriers in 1940s American Business (New York: Free Press, 2008). |

| 38. | Jesse Helms, memo to Ray Reeve, July 6, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 139; Ray Reeve, memo to J.D. Lewis, July 7, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 139. |

| 39. | Barry Malone, "Before Brown: Cultural and Social Capital in a Rural Black School Community, W.E.B. Dubois High School, Wake Forest, North Carolina," The North Carolina Historical Review 85, no. 4 (October 2008): 443–444. |

| 40. | David Cecelski, Along Freedom Road: Hyde County, North Carolina and the Fate of Black Schools in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 9. |

| 41. | Susan Jordan, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1966-67], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. |

| 42. | Hazel Jordan, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), May 8, 1966, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. |

| 43. | "Frolic Fan," letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1966-67], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. |

| 44. | Anonymous ("102 Pilot St.), letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 10, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. |

| 45. | Donald Hodge, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 21, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; Guadalupe Hudson, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 24, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; Daniel Jackson, letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), May 29, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140; "Nero, the Mad," letter to J.D. Lewis (WRAL), June 24, 1967, Lewis Family Papers, folder 140, July 22, 1967; Gwendolyn Gilmore, J.D. Lewis (WRAL), n.d. [ca. 1967], Lewis Family Papers, folder 140. |

| 46. | Guthrie Ramsey, Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 4. |

| 47. | Cash Michaels, "Memories of Teenage Frolics," The Carolinian, December 4, 1997. |

| 48. | Ibid. |

| 49. | "WOOK-TV," 1965 Broadcasting Yearbook, A–10. |

| 50. | Christopher Sterling and John Michael Kittross, Stay Tuned: A History of American Broadcasting, Third Edition (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002), 255–256, 351–352, 383, 415–416. |

| 51. | James Lee, "He Plays Teens Picks," Washington Star, [n.d.] ca. 1963. |

| 52. | Ibid. |

| 53. | "WOOK-TV's Coloring Book," Washington Afro-American, February 16, 1963; "WOOK's Insult to Our Race," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. |

| 54. | "Voice of the People: In Defense of WOOK-TV," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. |

| 55. | "WOOK Says it Isn't Just One-Color TV," Washington Star, February 11, 1963. |

| 56. | John Henry Murphy, Sr. started publishing the Afro-American newspaper in Baltimore in 1892. By 1960, under the control of Carl Murphy, the Afro-American published editions across the Mid-Atlantic States. The Afro-American papers cultivated an older and more middle class black audience than the viewers and listeners WOOK-TV and WOOK-radio targeted. |

| 57. | "Nation's First Minority Group TV Station to Broadcast Today," Chicago Defender, February 11, 1963. |

| 58. | Nan Randall, "Rocking and Rolling Road to Respectability," Washington Post, July 4, 1965. |

| 59. | "Dance Party (The Teenarama Story), Research Narrative," Box 2, Kendall Production Records, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum. |

| 60. | Beverly Lindsay-Johnson, interview with author, January 8, 2013. |

| 61. | "Voice of the People: In Defense of WOOK-TV," Washington Afro-American, February 23, 1963. |

| 62. | John Jackson, Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock & Roll (New York: Shirmer Trade Books, 2000), 168–169; Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock 'n' Roll Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 56. |

| 63. | Arnold Shaw, Honkers and Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues (New York: Macmillan, 1978), 376. |

| 64. | Quoted in Ward, Just My Soul Responding, 48. |

| 65. | WTTG-TV was was founded as a DuMont station and DuMont ended network operations in 1956. |

| 66. | "TV Jockey Profile: The Milt Grant Show," Billboard, February 6, 1961, 43. |

| 67. | Danielle Allen, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 5. |