Overview

|

| Joel Mann, Rebirth Brass Band, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2007. |

Through an examination of expressive forms, musicians, and artisans in post-Katrina New Orleans, this multi-media essay explores creolization as an approach to ethnographic work that seeks to describe and interpret cultural continuity and creativity. Creolization conjoins multiple sources in new identities and expressions, continuously co-mingling and adapting traditions in ways that link the local, regional, and global. In New Orleans and affected areas of the Gulf Coast, recovery in cultural terms can be described in the creative, transformative, and sometimes improvisatory dimensions of creolization. In its broadest sense, creolization is a useful way to address creativity in many variations and places.

The text of this essay is from Creolization as Cultural Creativity, eds. Robert Baron and Ana C. Cara. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2011. Published with permission.

Introduction

Doing fieldwork, public programs, and scholarly projects on expressive culture in Creole and other cultural settings in urban New Orleans and nearby French Louisiana over the last three decades suggests to me that creolization is part of the cultural continuity of community life and recreation of the social order—especially in the face of social and economic pressures or natural and unnatural catastrophes.1Creole expressive culture in French Louisiana—the rural parishes south and east of New Orleans to the Texas boarder—was the jumping-off point for discussion of the local and global aspects of cultural creolization in the original 1997 "Monde Créole" presentation to the meetings of the American Folklore Society in Lafayette, Louisiana, and now reprinted in Creolization as Cultural Creativity. This epilogue offers the counterpoint and complement of post-Katrina New Orleans, its own urban Creole communities, and, more broadly writ, the impact of creolized tradition and creativity on the general populace of the city/region. In a broader sense this perspective views the relationship between the conservation and transformation of cultures we find symbolized in expressive forms as a potentially universal creative process. The results of continuous co-mingling and adaptation of traditions to one another may produce continuities from past to present and ultimately future cultural arrangements where national or global outcomes may vie with local needs.

The etymological roots of the term "creole" in the Latin criar (to beget or create) point to a focus on creativity consistent with the language of cultural creolization. This approach allows us to make explicit the relations of cultural continuity and creativity in ethnographic work that attempts to describe and interpret the conjoining of multiple sources in new cultural identities and expressions, or to describe the mediation of complex identities through participation in unified creole processes and symbols of performance.

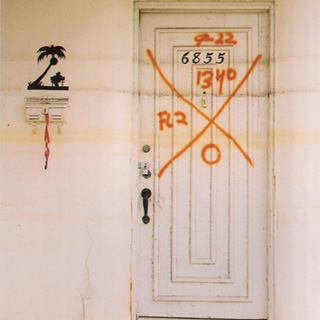

The natural and unnatural 2005 catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina and its post-storm flooding caused by engineering malfeasance in New Orleans offers a practical and compelling illustration of the role of cultural creolization as a framework in materially and socially rebuilding the city and affected areas of the region. It’s an area that includes communities identified as Creole, but, perhaps more importantly, it is a place where recovery in cultural terms can be described in the creative, transformative, and sometimes improvisatory terms of cultural creolization that extend beyond particular Creole communities.

Katrina and Intangible Culture

Hurricane Katrina caused over 1.2 million people to flee greater New Orleans, where levees failed to protect both urban and outlying areas. I have elsewhere described the cultural catastrophe that ensued as people evacuated their densely settled neighborhoods, many of which were covered by floodwaters.2Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina, eds. Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 305-328. Among these evacuees were the very musicians, traditional chefs, building artisans, ritual-festival celebrants of Carnival, and members of social aide and pleasure clubs who contribute to the core public cultural expressions for which New Orleans is famous. In the months and years that have followed the storm, flooding, and evacuation, much attention has gone to how these carriers of intangible culture in family and neighborhood networks made such an impact on the shared citywide vernacular culture. These consist of a series of overlapped cultural layers that include creolized forms such as traditional and brass band jazz played at second lines and clubs; Carnival celebrations such as the Mardi Gras Indians, African American and Creole Bone Men, and Baby Doll parade societies, the Zulu parade, White working-class walking societies, and Uptown elite float parades; Creole cottages and shotgun houses with their French, West African, and Caribbean sources; and neighborhood restaurants and family cooks such as Lil Dizzy’s (Creole and soul food) or Mandina’s (soul, Italian, Cajun mixed menu and recipes) that prepare local Creole and creolized traditional food, respectively.

|

| Nick Spitzer, Second line of funeral procession, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005. |

Creole culture and creolized forms of culture have served as agents of return and recovery in New Orleans. In the face of federal, state, and local government indifference and/or incompetence in responses to the disaster, local expressive forms, creative new uses of them, and realigned lateral relationships between African Americans, Afro Creoles and Whites in varied downtown and uptown neighborhoods all testify to the primacy of non-institutional forces at work in the recovery. On All Saints Day 2005, a jazz funeral was held for all those lost in the floods citywide. The sacred second line parade, which revealed what bands or portions thereof had returned to the city, made use of a form that conjoins the Catholic and broadly Christian funeral tradition of suggesting hope in a triumphant passage to the "gloryland" with West African ritual/festival processions. These generally include a somber procession to the cemetery by a "first line" of mourners and funeral officials, followed by an uproarious "second line" of neighborhood celebrants. The second line is broadly understood as having Senegambian sources for celebratory processions and is not unlike forms across the Caribbean that combine European formalities with African Diaspora improvisations. Roger Abrahams, for example, describes the elegant speakers at a "tea meeting" and the rough, mocking commentary on them by the "rude boys."3Roger D. Abrahams, The Man-of-Words in the West Indies:Performance and the Emergence of Creole Culture (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983). This carefree and sometimes unruly bunch is related to those who dance and drink behind the jazz funeral band after the body is "cut loose" at a New Orleans cemetery (though the entire procession, like the tea meeting, retains some formalized and "respectable" behavior).

The jazz funeral—normally a family and smaller neighborhood-specific creolized ritual-celebratory form—was expanded to stand for the mourning and hope, seriousness, and performative play associated with the present and future of the entire city/region. The return of particular family funerals around this time was also taken as a sign of "life" in the neighborhoods of New Orleans. As time passed and more people returned, such sacred second lines could again "walk through the streets of the city," in the words of a locally popular hymn. In so assembling, participants could see who had returned and what the condition was of churches, clubs, stores, homes, public housing, and the neighborhoods in which the marches took place. They could assess the "health" of the beloved music scene based on what brass band might be available in whole or part to musically lead the jazz funeral and its second line.

This symbolic expansion of returning performers also occurred with weekly secular second-line processions sponsored by a wide network of local social aid and pleasure clubs. For example, the return of specific parades such as the Tremé Sidewalk Steppers in spring 2007, two years after the deluge, was taken as a sign of recovery for the city as a whole.4Nick Spitzer, American Routes: Songs and Stories from the Road [Audio CD/CD-Rom] (Highbridge Company, 2008). Leaders of other clubs joining in with the Tremé second line took pains to suggest that they were marching not only for themselves but for the city as a whole—a place where new social configurations were already in play, which was brought out in my interview with a leader of a social club:

NS: How do you think the parade scene, the second lines, can help the city come back?

Buckner: Well we are a strong part of the culture. Actually, you look at the Indians and the second lines and we are the culture that go all year round. We are the culture that don’t stop. We don’t want to take nothin’ from Bourbon St. but, you know, when you talking ’bout partyin’ in the street, dancin’ in the street . . . this is dancin’ in the street. You can’t help but enjoy this.5Interview with Edward Buckner was broadcast August 22, 2007, on American Routes. See: Nick Spitzer, American Routes: Songs and Stories from the Road [Audio CD/CD-Rom] (Highbridge Company, 2008).

|

| Leidy Cook, Tremé Sidewalk Steppers, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2010. |

At the same time, Rebirth Brass Band leader and tuba player Philip Frazier sang the praises of the second line and its bands as instruments of the recovery, he also expressed concern about how many people were back participating in the clubs:

|

| Leidy Cook, Silence is Violence Peace Walk, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2010. |

The social aide and pleasure club model of mutual assistance, public entertainment, and cultural celebration has been invoked by a wide range of organizations from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like the resettlement agency Sweet Home New Orleans and the anti-crime group Silence Is Violence to nightclubs such as the Mother-in-Law Lounge and Tipitina’s, all of which have encouraged the return of the population and improvement of quality of life in the city by enlisting musicians, music, and traditional creolized festival forms to do so.

Signifiers of Return

No cyclical festive event defines New Orleans’ expressive culture more completely both locally and globally than Carnival or Mardi Gras. There was great concern that the annual celebration prior to Ash Wednesday and the forty days of Lent would not be enacted in 2006, the initial year after the deluge. Beyond the pragmatic realities that Mardi Gras in a badly wounded city would add to local economy and tax revenue even in a scaled-back form, the social and cultural counter-argument was made that Carnival was an essential rehearsal of return necessary for New Orleans civic life.6Roger D. Abrahams, Nick Spitzer, John Szwed, and Robert Farris Thompson, Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras and America’s Creole Soul (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). As a powerful and often satirical mingling of classes and cultures in public feasting, float parades, walking societies, krewe balls, and more, Fat Tuesday offered the first chance for a large public of those who had fled to Atlanta or Dallas, Baton Rouge, or Birmingham the chance to come back, view the conditions in the city, and participate in the event that is a primary part of natives’ sense of place through public performance and spectacle.

|

| Nick Spitzer, Mardi Gras Indian, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2004. |

The smaller traditional groups in Carnival, such as the Mardi Gras Indians, especially found themselves given greater local and national press attention than ever before as they appeared on the front page of both the New York Times and the New Orleans Times-Picayune on and after Mardi Gras day 2006.7Jon Pareles, "Mardi Gras Dawns With Some Traditions in Jeopardy," The New York Times, February 28, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/28/arts/music/28pare.html. In so doing, the "Indians," one of Carnival’s most creolized groups—uniting European, African Caribbean, and Native American structures, aesthetics, performances, costumes, and images—became a kind of report on the health of the city as a whole via their widening recognition both in the press and in the streets. In so doing, the status of Mardi Gras Indian tribes was temporarily elevated in a social order that increasingly was looking to such creolized cultural symbols and performances as evidence of recovery—a return to festive normalcy.

New Orleans music, especially traditional jazz, brass bands, and all manner of rhythm and blues, soul, and funk music, also stands for the city as a year-round signifier to America and the world of the city’s cultural sources and resources. In addressing the role that musicians have played, I have opined that after Katrina the players often became "model citizens," in so far as they were viewed as heroic carriers of the endangered intangible culture. They had become workers (at play) on behalf of the neighborhoods, nightclubs, and second-line parades in need of performers and performance to again become vibrant symbols of the community.8Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 305-328.

I interviewed the Creole pianist, producer, and songwriter Allen Toussaint—nationally known for his rhythm and blues and soul recordings. He had early on become a major spokesperson for the cultural recovery during the dark days of September 2005, during his evacuation to New York City. The locally revered musician noted that the "spirit didn’t drown," as he enumerated the loss of his Gentilly neighborhood home and its contents, then under eight feet of water: a Steinway grand piano, all his sheet music, and personal recording archives. The logical extension of his thinking, we agreed, was that there was no water line on music, or the soul. He could still perform, record, and produce music. It was a simple but profound realization about how intangible culture can survive, even thrive, under adversity and be recreated to greatness under new, heightened conditions—a kind of vernacular humanities that creolized Catholic teachings with experience and phenomenological knowledge of music.

|

| Guillaume Laurent, Allen Toussaint at Jazz à Juan, Juan-les-Pins, France, 2009. |

Allen Toussaint’s repertoire blossomed as he remade his upbeat social anthem from the 1970s, "Yes We Can Can" (originally written for local body shop man and singer Lee Dorsey of "Sittin’ in Ya-Ya" fame, and later made a hit by the Pointer Sisters in 1973). Toussaint sang with the most muscular and funky voicing he had mustered in over twenty years. "Yes We Can Can" was the first track on the Our New Orleans 2005: A Benefit Album CD that raised over a million dollars for Habitat for Humanity’s efforts to create new housing—a "Musicians Village" in the city.9Various Artists, Our New Orleans: A Benefit Album (Nonesuch Records, 2005). It instantly became the soundtrack of recovery, blaring from radios as hammers rang, saws cut, and backhoes cleared throughout the city. At the same time, Toussaint’s minor key and slow tempo on another song on the CD, "Tipitina and Me"—a variation on his mentor Professor Longhair’s jaunty "Tipitina"—presented a darkly luminous mood that carried the listener from funereal to hopeful thoughts about the city’s "resurrection," as Toussaint called it in 2005. Toussaint as a piano professor nouveau of the next generation demonstrated his authority in the role with a repertoire diversity that showed cultural creolization in the Afro-urban pop music with a 1970s-era message of inclusiveness and tolerance that prefigured the then soon-to-be President Obama’s message of hope ("Yes We Can"). Was Toussaint’s use of "Can Can" the kind of intensifier often used in creole languages? He also invoked the nineteenth-century New Orleans Creole classicist, French Jewish composer/performer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, in his haunting rendition of "Tipitina and Me." If "Can Can" was uplifting for recovery workers, then "Tipitina and Me" captured the night mood with candles burning before the power and the neon lights and club life had returned.

Toussaint then joined forces with Elvis Costello, the eclectic British rocker and lover of New Orleans music, on the CD River in Reverse, one of the first recordings made in New Orleans after Katrina in December 2005—the studio session of thematic songs about the disaster was emblematic of the nascent return of musical infrastructure. In 2009, Toussaint continued his solo efforts with a new recording of old New Orleans jazz modernist classics under the title of Thelonious Monk’s The Bright Mississippi. In his commentary on the recording, Toussaint returned to Christian metaphors for the city’s triumph over misfortune, but he replaced "resurrection" with a sense of the birth of new creative possibilities: "Spiritually Katrina was a baptism as far as I’m concerned. Many wonderful things came out of Katrina and are still going on and will be going on forever. That is quite a jolt in life to have to flex new muscles in every way, physically and spiritually. So I find Katrina to be much more of a blessing than a curse. Not only for myself, but for many that may not recognize it that way."10Interview with Allen Toussaint that aired August 2009 on American Routes.

Beyond the recovery and revaluation of artists, the question was raised whether New Orleans jazz as a whole would again be heard regularly in the recently submerged city. Traditional jazz emerged at the end of the nineteenth century—a period of huge repression for people of color. It was a brutal social transition for Creoles and African Americans—who were jazz’s primary early creators and players—as the hope of post–Civil War Reconstruction faded into the Jim Crow era. Writer Ralph Ellison later suggested that jazz’s birth and growth was a "freedom statement," "Constitution," and "Bill of Rights" for African Americans. In New Orleans, Creoles, African Americans, and some Euro-Americans (especially Italians) have long played the music.11Personal communication, Robert O’Meally, 2004. Early jazz had mostly European instrumentation (excepting the African-descended banjo and in some sense the use of drums even in manufactured kit configurations), a musical and social connection to US military and Catholic saints’ day parades, and African/Caribbean/American-inflected performance practices, rhythms, scales, harmonies, and associated street dance forms. Early New Orleans jazz has long been distinguished more by style (heterophony and group improvisation) rather than repertoire—the latter may include parlor and popular songs, hymns, blues, and marches.

|

| Derek Bridges, Dr. Michael White plays the jazz funeral for Doc Paulin, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2007. |

Over a century after its emergence, the post-deluge question was, will New Orleans traditional jazz—with all its creolized aspects and neighborhood base of performance—survive in a depopulated city of destroyed neighborhoods? One answer in the affirmative was from clarinetist and musical activist Dr. Michael White. White famously lost to the floodwaters an important personal collection: thousands of books and rare recordings, original sheet music and correspondence from now deceased musicians, historic photographs and antique instruments that belonged to legendary artists such as King Oliver and Sidney Bechet. In an intensely creative several years after the catastrophe, the mild-mannered humanities professor composed nearly forty new tunes in traditional jazz style!12The CD containing some of these is the 2008 Blue Crescent on Basin Street Records: New Orleans. White had previously made much of this connection to elder jazz musicians whom he had learned from (on records or in person), been advised by, or played with, musicians such as George Lewis, Danny Barker, and Doc Paulin. He referred to these and other players of traditional jazz as now "dancing in the sky" and made a recording of the same name also on Basin Street Records prior to the floods of 2005. It was an unprecedented act in the recent history of the music. Michael White also returned to a vigorous schedule of teaching at Xavier University (the only black Catholic university in North America), playing locally with the new brass band stylists he had previously eschewed as not traditional enough, and touring nationally and globally. All of which—along with other notable musicians—brought new attention in national and international press to New Orleans’ cultural revival as a sign of larger material, social, and economic recovery.

The same report of a huge new creativity and musical output would include a spectrum of players and institutions. The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival—its racetrack grounds badly damaged—was, like Mardi Gras itself, able to mount an event in 2006. It was produced with huge support from the public, musicians, and politicians who felt that the sprawling—sometimes chaotic, sometimes controversial—commercial celebration of the culture could not be allowed to cease for economic, public relations, and, ultimately, emotional and spiritual needs of the citizenry.

Soul queen Irma Thomas made a new choice: to sing the blues (previously not appropriate to her image as an urbane progressive soul singer) and to update classic blues woman Bessie Smith’s own tale of flooding, "Backwater Blues," from the 1927 inundations. Likewise, Creole pianist and sometime carpenter Eddie Bo (Edwin Bocage), in his late seventies, reawakened his building skills to repair homes of family and friends while working on new recordings such as his improvised, creolized version of "When the Saints Go Marching In," taking the old familiar sometimes clichéd song to another level by creating it anew in improvised words and music. At the end of the session recorded in October 2005, Eddie Bo addressed his own and the broader New Orleans public’s need to return, live in, and rebuild the cityscape by memorably concluding, "I want to be in that number."13Edwin Bocage, as quoted in Various Artists, Our New Orleans: A Benefit Album (Nonesuch Records, 2005).

|

| Nick Spitzer, Eddie Bo, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2005. |

A sixth-generation Creole craftsman from Algiers Point, Bo also readily suggested that his work as a carpenter was as creative as making music:

Bocage: We, as Bocage youngsters, had to learn to do, the craftsman, when he was five. All the males had to learn how to start off and build. . . . And I think we also had the shipbuilders and . . . engineers in the family. So they taught us what might be of interest to us, and what might help us out as far as having another skill other than what you choose. If you tend to choose something else, you would always be able to fall back on that.NS: And what skills did you learn as a builder?

Bocage: Bricklaying and carpentry was basically what my dad did, so I had to learn to do it too.

NS: Did you like that work when you did it?

Bocage: Oh yes. I love it as much as the music.

NS: Really?

Bocage: Yes, indeed. I love to stand back and look at what I put together. And you know, because I know it is constructed properly. I know that and then there is always new techniques and try to learn around everybody I go around.14Interview was broadcast November 2, 2005, on American Routes.

Creole Craftsmen

In a city famed for its music and (now partly destroyed) built environs, the linkage of creativity between work and play among Creole craftsmen—many of whom had been part of multiple-generation families of building artisans since the antebellum times of their gens de couleur libres ancestors—was a powerful addition to the discourse of recovery and rebuilding. Music could temporarily reassemble the artist families and their audiences of natives and visitors alike; however, the question of rebuilding the old infrastructure of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century wood and masonry houses as well as dealing with shattered brick subdivisions and moldy sheet-rocked (not old Creole plaster) interiors remains to this day. Still, in a city recognized for a bon vivant attitude, the efforts of Creole and other building artisans revealed a work ethic that could aid the recovery of New Orleans.

The late Earl Barthé was a renowned sixth-generation, self-identified Creole of color plasterer from the Seventh Ward Gentilly neighborhood. A leader in the Creole Fiesta and later a National Heritage Fellow recipient in 2005, Barthé’s ornamental plaster was created with a sense of musicality. Earl compared the work to his favorite performances, noting that he was just as happy listening to his sister Débria (now deceased), an opera singer performing Carmen, as playing the records of Muddy Waters or Ray Charles on the job. Barthé said that Carmen had the "plastering beat" and went a step further in the analogy of musical style to, particularly, the Creole plasterer’s craft: "You run the mold and then you place the dentils, those little square things that are cast and placed in the mold. It all has to be in tune. When you run your arch, you gotta put your corbel on the bottom. That’s like the big bass. It looks like a bass. So the musicians as I spoke about like Milford Dolliole and Tio with Chocolate Milk, which is a funk band—and there were many others that were good plasterers and musicians—they had that musical touch. They’d be singing the songs of Muddy Waters . . . and be placing dentils and ornaments into this cornice."15Earl Barthé, as quoted in Nick Spitzer, "The Aesthetics of Work and Play in Creole New Orleans," in John Ethan Hankins and Steven Maclansky, eds., Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002), 123.

|

| Neil Alexander, Earl Barthé, New Orleans, 2002. © Neil Alexander/neilphoto.com |

Earl Barthé was dubbed the "Jelly Roll Morton of plastering," owing to his similar features, loquacious style, and love of music as a metaphor for his work. His "articular" plaster medallions were featured in the museum exhibit and catalog Raised to the Trade": Creole Building Arts of New Orleans.16Jonn Ethan Hankins and Steven Maklansky, eds., Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002) Barthé and family took refuge from Katrina in Cypress, Texas, and returned months later to repair their heavily damaged home, their workshop, and the homes of their many clients. In a 2007 interview Barthé expressed longing for the cooperative social order of Creole workers he knew as a youth, in hopes that such reciprocal labor could be applied to the recovery: "The Creoles would build each other’s houses. So they would have the cement masons to do the foundation. Bricklayers, carpenters to do the framing, roofers, and plasterers and painters would come in and finish up. And they would say, ‘We’re going to start your house this week’—so they would lay the foundation and frame it."17Kate Ellis, Stephen Smith, and Nick Spitzer, Routes to Recovery, American Radioworks, 2007.

|

| Neil Alexander, Large plaster medallion in a New Orleans shotgun house, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2002. What some in the trade refer to as a "Cadillac finish," this decorative element normally found in a grand home or hotel lobby is installed here by the artisan in his own residence. © Neil Alexander/neilphoto.com |

The late Earl Barthé’s social dream and work aesthetics, along with the late Eddie Bo’s approach as Creole craftsman, are slowly being put into practice across the cityscape by a wide array of non-profit organizations and private developers, following the collaborative model to varying degrees and through a renewed focus on continuity in the building arts as taught informally in family businesses and institutionally at specialty elementary schools and community colleges. The cooperative labor ideal has been enacted through college, church, and community assistance networks nationwide that sponsor "voluntourism" for visitors who work on building or repairing homes. Outside artists, scholars, students, and professionals have also contributed to the collective rebuilding effort as part of the city’s "brain gain" in a fulfillment of the traditional "social aid" side of the original social aid and pleasure clubs. The "pleasure" aspect of a culturally based lifestyle imbued with music, food, Carnival, and joie de vivre is, of course, also available. Owing in part to the West African/Mediterranean/Caribbean aspects of New Orleans society, these enjoyments and entertainments—like the historic linkage of music and the building arts—are seen as related to concerns for the future of the social order. The hope of many New Orleans craftsmen and others is to more fully enact a collaborative rebuilding, at a WPA (Works Progress Administration) level not seen since the 1930s, wherein young apprentice builders learn the trades while building sweat equity and gaining knowledge of finance and entrepreneurship so that learning the skills and assisting others can translate into a livelihood that repopulates the city with skilled homeowners in the neighborhoods they helped rebuild and will ultimately stabilize by their presence.

Culture as Recovery

In the difficult days that followed the floods of 2005, there were many calls to move New Orleans upriver by earth scientists, social scientists, politicians, and others.18For one good example, see: Robert Giegengack and Kenneth R. Foster, "Physical Constraints on Reconstructing New Orleans," in Eugenie L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons From Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 13-33. There may have been good science behind urging historic city dwellers to leave problematic natural environs for a rural location one hundred miles north in Morganza, Louisiana, but it was amateur social policy that ignored the deep symbolic associations of place, culture, and community in peoples’ lives. There was also the dilemma, faced by governments, NGOs, foundations, and private investors, that the material infrastructure of New Orleans was already in terrible shape prior to the deluge—with collapsing and abandoned buildings, poor roads, dilapidated public schools, and, of course, a haphazard and permeable levee system surrounding a partly below sea level "bowl" of a city, located on a rapidly eroding coast line. The focus of much disaster recovery anywhere is on infrastructure, but in New Orleans the case was made that as a kind of Venice of the vernacular with a whole lot less water in it than that other great city of the arts, a focus had to be as much on restoring the intangible culture by encouraging the return of the citizenry—the carriers of the culture.

Humorously, some said that intangible culture was anything without a waterline on it. To this I would add that it was always hard to find a native New Orleanian, a new settler, or a tourist to the Crescent City who stayed or moved here because he or she thought the infrastructure was especially attractive.19I must admit, though, that we probably will never know exactly how many people left New Orleans before Katrina or never returned after it because of the city’s weak infrastructure, limited economic opportunities, or racial and class barriers. The comedian Harry Shearer added, in multiple media appearances, that after Katrina, "New Orleans broken is far better than other places fixed."

What made the city worth enduring chronically broken infrastructure, often retrograde policing, weak and illicit governance, and subpar public schools was the creative and "easy" lifestyle associated with enduring creolized cultural vernaculars of the cityscape—a legacy of dominantly a French/Spanish West African society, later leavened with immigrants from the American South, Germany, Ireland, and Italy, among many other sources. New Orleans, as a cultural and social order created from these diversities in a provincial location of geographic and climatic difficulty, of religious difference from the rest of the United States, in a former slave society with all its post-colonial problems, was now more than ever relying on the power of the expressive cultural continuities that set the city apart from the South and that made it more kindred to the Caribbean. The advantage of looking at the city this way geographically has recently been reaffirmed by archaeologist Shannon Dawdy’s anthropological history, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans.20Shannon Lee Dawdy, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans (University of Chicago Press, 2009). Dawdy shows the emergent eighteenth-century polyglot port city that developed its own "rogue colonialism" as part of a kind of organic and creative economic and cultural creolization process. Rogue colonialism reconfigures and conjoins the many cultural streams into the urban social landscape in a manner more adaptive and appropriate than conventionally understood metropole-periphery relationships of governance, economy, and society based in formal institutions of colonial powers (here, France, then Spain, and, I add, America and the Confederacy) usually allow for. I have referred to New Orleans as being "south of the South."21Nicholas R. Spitzer, "The Creole State: An Introduction to Louisiana Traditional Culture," Louisiana's Living Traditions, 1985. The relative worldliness of the city is noted in terms of its location on the northern rim of the Caribbean culture area. Andres Duany, the new urbanist architect and planner, confronted the city’s infamous disorder and corruption: "And then I realized . . . that New Orleans was not an American city. It was a Caribbean city. Once you recalibrate, it becomes the best governed, cleanest, most efficient, and best-educated city in the Caribbean. New Orleans is actually the Geneva of the Caribbean."22Quoted in Wayne Curtis, "Houses of the Future," The Atlantic, November 2009. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/11/houses-of-the-future/7708/

New Orleans’ community-centric Creole and creolized cultural expressions have moved increasingly to the center of local public discourse in the years after the floods. Partly this was possible because much deeply traditional life had long remained in the city, and also because the tradition writ large has been one of explicit improvisation—be it musical, in cuisine, in the built environs, or in Carnival aesthetics. An initial recovery suggestion was that the city—with its largely intact and distinctive eighteenth- and nineteenth-century high-ground landscape and its continuing Latinate laissez-faire attitudes—was well pre-adapted to further develop a gaming economy as a kind of historic competitor to Las Vegas. Public ridicule and social awareness in a far less complacent post-catastrophe city quickly deflated such speculation. Beyond the previously dominant focus on preserving the past in material terms, the question of the cultural future had become central in New Orleans’ public discourse.

Although concerns for authenticity are not fashionable in some academic circles, the new civic discussion often asked how the city could remain "authentic," meaning historic and connected to its cultural legacies, compared to the rest of the United States. The focus, however, was on linking the cultural past to an "authentic future."23Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 308. At its most realized, the idea is that cultural expression in the streets and clubs would remain on an intimate local scale defined as the creative zone where creolized culture met a need for continuity, neighborhood-based culture, the arts, and economic sustainability—all founded on local diversity and new economic approaches to creative "industries," cultural tourism, environmental services, public education, and urban planning alongside more traditional areas such as shipping, petrochemical industries, finance, and medicine.

Culture as the primary agent of return to and recovery of New Orleans has been central to the mission of NGOs like Sweet Home New Orleans that early on emphasized the resettlement of the musicians, ritual/festival participants, chefs, and building artisans who made the city distinctive and attractive. While infrastructure in the form of schools, housing, medical facilities, highways, and drainage is essential, a public narrative emerged, claiming that, without cultural continuity linking the past to the future, there is little point in developing infrastructure for its own sake. There had to be a sense of possibility for a cultural future to justify the efforts to rebuild and reinvest.

While a social justice perspective argues for careful planning and infrastructure development to improve the quality of life for the population, in New Orleans it is arguably the laterally connected, intimate, creative, and creolized "way of life," in the words of jazz saxophonist and Mardi Gras Indian Donald Harrison, that has kept the city afloat through this perilous passage.24Harrison’s remark was made at the Penn Institute for Urban Research Seminar, Arts in the City: Can the Arts Revive Our City and the Nation’s Economy? Philadelphia, March 2, 2010. I distinguish "way of life," as an organic cultural attribute, from "quality of life," which more often is a kind of add-on or enumerative set of features favored by advocates of economic development based in "creative economy"—most prominently Richard Florida, who ironically has New Orleans low on his quality-of-life rankings compared to many cities with far less organic "way of life" depth. This way of thinking liberates the notion of infrastructure to serve as a human need in society that supports a way of life, but it does not embody or create that society. Rather, it is mainly the agency of creative tension between continuity and transformation of culture that generates the livable future on the terms I have outlined.

In this way, New Orleans has begun to emerge as a national model in recessionary times for cities that build on the instrumental and expressive aspects of their vernacular culture to move beyond devalued landscapes and neighborhoods, high unemployment, and a general distrust of national economic institutions based in Wall Street or Washington. While few urban centers have the Creole cultural inheritance of New Orleans, many cities with historic cultural influences and new immigrants are creolized at the community level in certain ways. Some are just beginning to look deeply at the resources and applications that are available in this way of thinking. New Orleans’ civic and cultural leaders increasingly sense the role that the city could play in shaping a national discourse about cultures that are distinct and shared at the local level via expressive forms, with their artistic proponents leading the way.

However, New Orleans has not historically been a place for resident intellectuals bent on describing how the rest of America could learn from the city’s creole cultural processes of tradition and improvisation as a way to better understand potential for viewing creative freedom in terms that reconcile the pluribus and unum in localities nationwide. The New Orleans tendency instead has been to simply perform the culture’s traditions of creativity here or on the road, and so draw adherents, be they tourists and music fans, architects and foodies, scholars and policy wonks, or globalization theorists and chairpersons of federal agencies devoted to the arts and humanities.

|

| Thomas Helbig, Cedric Watson, Rudolstadt, Germany, 2010. |

One attempt to nationally present the idea of New Orleans Creoles—specifically, a jazz banjo player from New Orleans named Don Vappie as an ultimate, socially adaptable, yet culturally grounded American—was a PBS film called American Creole.25American Creole: New Orleans Reunion, DVD, Documentary directed by Michelle Benoit and Glen Pitre, Louisiana Public Broadcasting. 2006. The documentary was planned in antediluvian days to show Vappie and his large kin network functioning effectively in an array of occupations (including professional musicians in New York and Los Angeles) and communities nationwide. Post-Katrina flood waves redirected the project toward how a creative Creole like Vappie could use the cultural expression of jazz and his family ties to help people return to and rebuild New Orleans from the musician community outward.

On the larger question of re-understanding American vernacular culture, other artists, like the well-known blues singer Taj Mahal and the rising young Louisiana Creole fiddler Cedric Watson, have independently suggested that the United States might best be understood as a "Creole nation."26Interviews from Nick Spitzer, American Routes, 2003 and 2010. In a Creole nation one imagines that culture is viewed as a creative creolizing process where group identities show both continuity, synthesis, and differential change, rather than the more linear culturally centric or islanded multicultural conceptions of diverse social orders. These particular artists that gave a voice to such observations are from backgrounds that reflect Creole cultural contact and transformation: Taj Mahal is of African American and British West Indian parentage; Cedric Watson claims Louisiana Creole, Mexican Spanish, Native American, and African American cultural forebears. They are connected to Creole societies of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, and both are aware of the creolization in their personal identities and musical expressions.

From a more critical point of view some scholars, especially anthropologists, have debated the utility and appropriateness of even using "creolization" as a way to universally describe and interpret the processes of continuity and creativity in cultural identities, expressions, ecologies, economies, and related realms.27Viranjini Munasinghe, "Theorizing World Culture through the New World: East Indians and Creolization," American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 549-562. For a discussion of Viranjini Munasinghe's article see American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 563-592. A key concern raised in the discussion is that specific Creole societies often recreate either the insular and intolerant hierarchies of the former colonial metropole in the provincial setting or, as they evolve into settled ethnic communities, find ways to exclude those who do not fit into the reified mix of genealogy and cultural markers used to maintain those ethnic boundaries. Examples from New Orleans and other Louisiana Creole communities are not uncommon, and Viranjini Munasinghe describes the plight of marginalized East Indians in the colonially derived West Indies Creole communities.28Viranjini Munasinghe, "Theorizing World Culture through the New World: East Indians and Creolization," American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 549-562.

Conclusion

Still, we are bound by our comparative and ethnographic traditions to find ways to describe and interpret how cultural communities in the present maintain links to varied pasts—often multiple Old Worlds—and creatively address the present and future in transformations that allow for recognizable linkages between times and places. In this light, cultural creolization is a useful way to address traditional creativity in many forms, variations, and places in the world. The people called Creoles who have made that process explicit in their identity and aesthetic expressions of their culture will continue to discuss, argue, and sometimes disagree about group boundaries; and those feeling excluded from Creole groups may add to the discontent.

|

| Erin Nekervis, Rebirth Brass Band, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2010. |

The question of "Who is a Creole?" will likely remain, but what has emerged as more broadly significant is that cultural creolization as a means of describing tradition, creativity, and continuity from past and present into the future of human communities is a hopeful and engaged human discourse when compared to the alternative: global monoculture and assimilation within nation-states.

New Orleans is distinctive within the United States with its Carnival, music, cuisine, and building artisanship, but shares these expressions broadly with Creole societies of the Caribbean through parallel development in the New World, African European plantation colonial sphere as well as long-term intraregional migrations. The city has long been a kind of Creole hearth of creativity and symbolic soul for America and anywhere in the world where creolization as a vernacular process creatively connecting the past to the future of community-based culture has not been made explicit. As Rebirth Brass Band leader Philip Frazier says, "Without New Orleans, there is no America."29Quoted in Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 326.

Recommended Resources

Abrahams, Roger D. The Man-of-Words in the West Indies:Performance and the Emergence of Creole Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Abrahams, Roger D., Nick Spitzer, John Szwed, and Robert Farris Thompson. Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras and America’s Creole Soul. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Baron, Robert and Ana C. Cara, eds. Creolization as Cultural Creativity. University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

Birch, Eugenie Ladner and Susan M. Wachter, eds. Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Dawdy, Shannon Lee. Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Dawdy, Shannon Lee. "Understanding Cultural Change through the Vernacular: Creolization in Louisiana," Historical Archaeology 34:3 (January 1, 2000): 107-123.

Gushee, Lawrence. Pioneers of Jazz: The Story of the Creole Band. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hankins, Jonn Ethan and Steven Maklansky, eds., Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002.

Hirsch, Arnold Richard and Joseph Logsdon. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Munasinghe, Viranjini. "Theorizing World Culture through the New World: East Indians and Creolization," American Ethnologist 33:4 (November 2006): 549-562.

Stewart, Charles, ed. Creolization: History, Ethnography, Theory. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, 2007.

Thompson, Shirley Elizabeth. Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Music and Films

Benoit, Michelle and Glen Pitre, American Creole: New Orleans Reunion. DVD, Documentary, Louisiana Public Broadcasting, 2006.

Spitzer, Nick. American Routes: Songs and Stories from the Road. Audio CD/CD-Rom, Highbridge Company, 2008.

Spitzer, Nick. Zydeco: Creole Music and Culture in Rural Louisiana. Center for Gulf South History and Culture, 1986.

http://www.folkstreams.net/film,181

Various Artists. Our New Orleans: A Benefit Album. Audio CD, Nonesuch Records, 2005.

Links

American Routes

http://americanroutes.wwno.org/.

American Federation of Musicians: New Orleans Local 174-496

Union of New Orleans Musicians

http://www.neworleansmusicians.org/.

Folk Life in Louisiana

http://www.louisianafolklife.org/.

NOLA.com

"Everything New Orleans"

http://www.nola.com/.

Nick Spitzer on New Orleans' Cultural History

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4833057.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Creole expressive culture in French Louisiana—the rural parishes south and east of New Orleans to the Texas boarder—was the jumping-off point for discussion of the local and global aspects of cultural creolization in the original 1997 "Monde Créole" presentation to the meetings of the American Folklore Society in Lafayette, Louisiana, and now reprinted in Creolization as Cultural Creativity. This epilogue offers the counterpoint and complement of post-Katrina New Orleans, its own urban Creole communities, and, more broadly writ, the impact of creolized tradition and creativity on the general populace of the city/region. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina, eds. Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 305-328. |

| 3. | Roger D. Abrahams, The Man-of-Words in the West Indies:Performance and the Emergence of Creole Culture (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983). |

| 4. | Nick Spitzer, American Routes: Songs and Stories from the Road [Audio CD/CD-Rom] (Highbridge Company, 2008). |

| 5. | Interview with Edward Buckner was broadcast August 22, 2007, on American Routes. See: Nick Spitzer, American Routes: Songs and Stories from the Road [Audio CD/CD-Rom] (Highbridge Company, 2008). |

| 6. | Roger D. Abrahams, Nick Spitzer, John Szwed, and Robert Farris Thompson, Blues for New Orleans: Mardi Gras and America’s Creole Soul (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006). |

| 7. | Jon Pareles, "Mardi Gras Dawns With Some Traditions in Jeopardy," The New York Times, February 28, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/28/arts/music/28pare.html. |

| 8. | Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 305-328. |

| 9. | Various Artists, Our New Orleans: A Benefit Album (Nonesuch Records, 2005). |

| 10. | Interview with Allen Toussaint that aired August 2009 on American Routes. |

| 11. | Personal communication, Robert O’Meally, 2004. |

| 12. | The CD containing some of these is the 2008 Blue Crescent on Basin Street Records: New Orleans. White had previously made much of this connection to elder jazz musicians whom he had learned from (on records or in person), been advised by, or played with, musicians such as George Lewis, Danny Barker, and Doc Paulin. He referred to these and other players of traditional jazz as now "dancing in the sky" and made a recording of the same name also on Basin Street Records prior to the floods of 2005. |

| 13. | Edwin Bocage, as quoted in Various Artists, Our New Orleans: A Benefit Album (Nonesuch Records, 2005). |

| 14. | Interview was broadcast November 2, 2005, on American Routes. |

| 15. | Earl Barthé, as quoted in Nick Spitzer, "The Aesthetics of Work and Play in Creole New Orleans," in John Ethan Hankins and Steven Maclansky, eds., Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002), 123. |

| 16. | Jonn Ethan Hankins and Steven Maklansky, eds., Raised to the Trade: Creole Building Arts of New Orleans (New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art, 2002) |

| 17. | Kate Ellis, Stephen Smith, and Nick Spitzer, Routes to Recovery, American Radioworks, 2007. |

| 18. | For one good example, see: Robert Giegengack and Kenneth R. Foster, "Physical Constraints on Reconstructing New Orleans," in Eugenie L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons From Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 13-33. |

| 19. | I must admit, though, that we probably will never know exactly how many people left New Orleans before Katrina or never returned after it because of the city’s weak infrastructure, limited economic opportunities, or racial and class barriers. |

| 20. | Shannon Lee Dawdy, Building the Devil’s Empire: French Colonial New Orleans (University of Chicago Press, 2009). |

| 21. | Nicholas R. Spitzer, "The Creole State: An Introduction to Louisiana Traditional Culture," Louisiana's Living Traditions, 1985. |

| 22. | Quoted in Wayne Curtis, "Houses of the Future," The Atlantic, November 2009. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/11/houses-of-the-future/7708/ |

| 23. | Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 308. |

| 24. | Harrison’s remark was made at the Penn Institute for Urban Research Seminar, Arts in the City: Can the Arts Revive Our City and the Nation’s Economy? Philadelphia, March 2, 2010. I distinguish "way of life," as an organic cultural attribute, from "quality of life," which more often is a kind of add-on or enumerative set of features favored by advocates of economic development based in "creative economy"—most prominently Richard Florida, who ironically has New Orleans low on his quality-of-life rankings compared to many cities with far less organic "way of life" depth. |

| 25. | American Creole: New Orleans Reunion, DVD, Documentary directed by Michelle Benoit and Glen Pitre, Louisiana Public Broadcasting. 2006. |

| 26. | Interviews from Nick Spitzer, American Routes, 2003 and 2010. |

| 27. | Viranjini Munasinghe, "Theorizing World Culture through the New World: East Indians and Creolization," American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 549-562. For a discussion of Viranjini Munasinghe's article see American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 563-592. |

| 28. | Viranjini Munasinghe, "Theorizing World Culture through the New World: East Indians and Creolization," American Ethnologist 33, no. 4 (November 2006): 549-562. |

| 29. | Quoted in Nick Spitzer, "Rebuilding the Land of Dreams with Music," in Eugenie Ladner Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 326. |