Overview

|

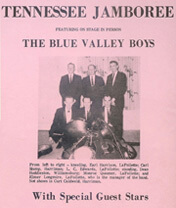

| Tennessee Jamboree poster, LaFollette, Tennessee, late 1960s. |

Part of a wave of local, post-WWII "barn dance"-style, country music shows, the Tennessee Jamboree radio program was modeled on earlier, nationally popular programs like Nashville's Grand Ole Opry and Chicago's National Barn Dance. The Tennessee Jamboree reimagined and reshaped the genre into a platform for local cultural expression. Drawing upon newly recovered broadcasts, interviews with Jamboree participants, and images from the Tennessee State Archive and Library, this essay resituates the Tennessee Jamboree within several historical and cultural contexts that help to illuminate the expressive life of Lafollette, Tennessee, the broad sweep of regional broadcasting, and the incomplete chronicle of the barn dance genre.

"The Tennessee Jamboree" is part of the 2008 Southern Spaces series "Space, Place, and Appalachia," a collection of publications exploring Appalachian geographies through multimedia presentations.

Introduction

. . . Hello everybody and welcome friends to your Tennessee Jamboree here on another Saturday evening. I'll tell you what, it's good to have you tuned our way. Wherever you might be, hope you enjoy the next little bit now. We've got all the boys and girls here present and accounted for. So why don't you kindly turn your dial up a little bit and stay around with us for the next hour, cause we’ve got Monroe, Big Red, Ol' Sidro L.C., and the trio and all here on the Tennessee Jamboree. So we hope you'll stay around with us . . .

The Tennessee Jamboree, a country music radio variety show, aired between 1953 and 1978 on AM station WLAF in LaFollette, Tennessee. Across twenty-five years, the Blue Valley Boys and Girls, the show's featured performers, picked, sang, and entertained each Saturday night for listeners in the Campbell Country broadcast area. Recognizable as a derivative of the nationally popular radio "barn dance" genre, the Tennessee Jamboree reshaped the established formula into a locally-based format of cultural expression. During the summers of 2007 and 2008, while part of a fieldwork and research team sponsored by the Cumberland Trail State Scenic Trail in East Tennessee, I helped locate tapes containing several complete, and some fragmented, original broadcasts. These rare recordings, spanning 1965 to 1977, reveal a thriving radio program, one steeped in the nationally broadcast country music variety show tradition, yet more considerably marked by the particular circumstances and preferences of Appalachian East Tennessee and, even more so, of LaFollette.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Blue Valley Boys, mid-1960s. |

Starting in the mid-1920s, the barn dance genre provided many US listeners an appealing entertainment format through which to negotiate rapidly changing social and cultural circumstances. Amid revolutionizing "modern" technologies, this "down-home" representation, marked by traditional values and "old time" country music, proved popular with rural, urban, and newly urban audiences. The genre thrived as powerful radio stations served swelling regional and national audiences. The airwaves that worked effectively to reduce distance, reconfigure place, and re-imagine communities often carried the rustic and comforting sounds of a barn dance. After World War II, as hundreds of new radio stations began to broadcast from small towns, a new wave of barn dance programs emerged, fashioned after national models like the National Barn Dance and the Grand Ole Opry. These postwar shows returned the genre to local communities, providing an alternative to the mass-mediated, distant worlds aurally constituted on popular network broadcasts. Just as so many of the long-established programs had aided the creation of regional and national audiences so did these smaller barn dance programs of the 1950s and 60s project and construct a sense of local identification.

For historians, the negotiation by the "listener" of complex national, regional, and local identifications has been a central, contested issue in radio scholarship. Susan Douglas describes the condition:

[Radio's] technologically produced aurality allowed listeners to reformulate their identities as individuals and as members of a nation by listening in to signs of unity and signs of difference. By the late 1920s "chain broadcasting" was centralizing radio programming in New York and standardizing the broadcast day. . . . Meanwhile, independent stations featured locally produced programs with local talent. Listeners could tune into either or both, and tie in, imaginatively, with shows that sought to capture and represent a "national" culture or those that sought to defend regional and local cultural authority.1Susan Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 57.

Douglas suggests that, though now mostly lost to us, the content/s and personalities of local radio were esteemed and sought-after. "Despite the familiar narrative that radio fans came to favor the networks because their program quality was superior," she writes, "the fragmentary evidence indicates that many listeners preferred their local and independent station, and loved announcers, singers, storytellers, and readers of news whose names and fame have not survived radio's highly ephemeral record."2Ibid, 79.

Due to the "ephemeral record" of local broadcasting, the scholarly attention given to the barn dance genre has tended to focus on a few of the larger nationally- and regionally-popular programs. These Tennessee Jamboree tapes offer a new glimpse into the overlooked, underrepresented, and frequently unobservable relationship between country music, small town radio, and cultural life. The tapes reveal that, even while reflecting the broader influences of the barn dance genre, small town programs offered listeners a way to frame their dispositions, animate their local spaces, and satisfy their tastes. As artifacts shaped by overlapping historical and geographical contexts, the tapes help us understand and interpret how a small town barn dance broadcast sought the polish of revered national programs while nurturing a more ad hoc small town spirit, how it aimed for variety and showmanship while operating on a do-it-yourself-scale, how it achieved broadcast professionalism while mainly employing industrious amateurs. Through the expressive practices of local musicians and entertainers, LaFollette area listeners found on their airwaves a particular constitution of their cultural life.

|

| Blue Valley Boys newspaper advertisement, LaFollette, Tennessee, late 1960s. |

In this essay I place the Tennessee Jamboree within several contexts, organized toward a progressive narrowing of focus. I will start with a discussion of the critical role of radio in rural life in the United States, before going on to outline the long-running country music radio (and later television) barn dance tradition, as it expanded nationally and as it developed within East Tennessee. These sections feature audio and video clips from several programs, included to create a fuller, richer, and more specific introduction to this resilient genre. Using documentary evidence and recent fieldwork, I will also explore relevant aspects of the history of LaFollette, of AM station WLAF, and the Tennessee Jamboree radio program. These traces will intersect as I conclude with a close description and the full audio of one representative Tennessee Jamboree broadcast. While marked by and situated within national and regional settings, the Tennessee Jamboree inhabited a local broadcast space and constructed over the airwaves an idealized aural representation of a southern Appalachian small town's culture.

Rural Radio

The introduction of radio into the rural United States in the 1920s brought outlying populations into an expanding "network of modernity."3Ronald R. Kline, Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 10. Along with the automobile, telephone, and electricity, radio emerged as a key technological component in the negotiations between rural people and government agencies over the future course of US cultural and social life.4Ibid. The diffusion of radio encouraged the transformation of rural life toward the cosmopolitan utilities of mainstream urban living. As Ronald Kline points out, for government officials interested in both uplifting and maintaining America's strong agricultural base, radio's presumed benefits included "the ability to relieve isolation, bring the city's culture of highbrow music and higher education to the country, and keep youth on the farm."5Ibid, 116.

|

| Marion Post Wolcott, A coal miner listens to his radio, West Virginia, 1938. |

With the onset of the Great Depression, radio's significance for rural families grew despite the lean conditions. During the 1930s, the number of farm families nationwide who owned a radio grew from twenty-one to sixty percent.6Ibid, 287. The appeal and importance of radio during this time cannot be exaggerated. "Poverty stricken families," writes C. Joseph Pusateri, "would choose to surrender an icebox or furniture or even a bed before they would part with their radio sets. Radio somehow symbolized lifelines to the outside world that must be preserved at virtually any cost."7Joseph C. Pusateri, Enterprise in Radio: WWL and the Business of Broadcasting in America. (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1980), 153. "Unlike other major technologies—automobiles . . . or trains—that move us from one place to another," adds Susan Douglas, "radio . . . worked most powerfully inside our heads, helping us create internal maps of the world and our place in it, urging us to construct imagined communities to which we do, or do not, belong."8Douglas, 5.

Richard Peterson explains the Depression-era situation:

For the potential consumer, radio entertainment had the great advantage of being free of charge, an especially important consideration in those . . . years. [R]adio had an almost magical power for rural people growing up in the 1930s, drawing families together and at the same time opening isolated communities to the larger world beyond the country and even the state.9Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 97.

To speak, however, of one common rural radio experience is misleading. Conditions were not equivalent across the country's vast regional and geographical expanses. Residents in southern regions, especially those in the rugged mountainous tracts, lagged in the acquisition of technology as compared with farmers elsewhere in the US.10Kline, 287. In Appalachia and the Deep South, income never kept pace with the national average. For farmers and miners throughout the southern mountains, the cost of radio was not easily absorbed.11Jacob J. Podber, "The Electronic Front Porch: An Oral History of the Early Effects of Radio, Television, and the Internet on Appalachia and the Melungeon Community." (PhD dissertation: Ohio University, 2001), 121. By 1930, when nearly half of midwesterners owned radios, only one in ten residents of the US South could say the same. But evidence does not suggest that radio was less popular or had less of an impact here. The social conditions simply developed differently as radio listening became a more communal experience, with several families often gathering at the homes of those who managed to afford the expensive device.12Ibid, 143-144.

|

| A couple listens to their radio, West Virginia, 1938. |

Even though rural listeners constituted a dedicated and sought-after audience, early radio stations emanated from larger population centers. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, while some locales boasted independent "farmer" stations, most rural dwellers received the signals of dominant clear-channel stations located in regional hubs. In an effort to regulate the airwaves and prevent signal interference, the FCC authorized these prominent stations to broadcast with high-power and to hold exclusive claim on their frequency, day and night. Without local stations, rural and small town listeners became adept at picking up signals and tuning in to programming from the many large stations.13Ibid, 132-133.

Radio's big-city bias changed after World War II. Eager to promote the growth of the medium, the FCC declared in October 1945 that it was resuming "normal consideration of applications for new stations." Broadcast radio entered a new era.14Pusateri, 221. Across the country, post-war entrepreneurs began to realize the commercial potential in radio and soon triggered an explosion of new AM, and now FM, stations. In contrast with radio's early period, during the late 1940s and early 1950s ambitious young broadcasters began to locate in smaller, underserved, and less-populated places. During the first few years following the war, the number of cities and towns with local radio service doubled.15Ibid. AM 1450 WLAF in LaFollette, Tennessee, took to the airwaves in 1953 and, for the first time, provided the town and surrounding county with a broadcast platform for cultural self-projection.

The Barn Dance Genre

In its form and in its spirit, the Tennessee Jamboree was a descendant and a refashioning of the national radio "barn dance." Country music, by way of early "hillbilly" music, achieved its national and international status not through recordings or song publishing, but through its dissemination on the many barn dance programs that came to dot the US soundscape.16Diane Pecknold, The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 15. From the birth of radio in the 1920s, to its height in the so-called "Golden Age" of the 1930s and 1940s, on through the post-war period, the onset of television, the birth of rock and roll, and the monumental cultural shifts in the second half of the twentieth century, the country music barn dance variety show, in its changing forms, has had a venerated place on the airwaves.

Although the first local barn dance program emanated from WBAP in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1923, it was the aptly-named National Barn Dance, launched one year later on Chicago's powerful WLS and broadcast across the Midwest — and later the nation — that secured the genre's popularity and stimulated the spread of similar programs. Crafted as a mass-mediated, imaginary representation of "old-fashioned 'country' sociables," the pioneering weekly production established the genre's standard with its showcase of fiddlers, square dancers, and balladeers, alongside a roster of regional, rural, and ethnic stock characters, all interacting in slapstick comedy routines and scripted bits.17Ibid, 16. Both the emerging corporate city stations, as well as smaller independent "farmer" stations originating in the hinterlands, sought to attract listeners from the countryside and urban areas. The romantic fantasy of the barn dance format proved up to the task.

Whether in small agricultural centers like Yankton, South Dakota, and Shenandoah, Iowa, or in regional hubs like Atlanta, Des Moines, or Wheeling, West Virginia, the barn dance format thrived. Perhaps more so than any other type of early radio programming, the popularity of the barn dance represented and informed a range of contemporaneous social issues. Throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, people increasingly migrated from rural to urban areas, often from south to north. With these major demographic shifts and reconfigurations, the national sentiments towards the binaries of rural/urban and old-fashioned/modern became increasingly conflicted. "[T]he nation's general ambivalence about rural life in the 20s, as well as mass migrations out of the country," writes Susan Smulyan, "may provide partial explanations for the popularity of the barn dance programs. Country music fused the conflicting responses to industrialization with the contradictory, somewhat romanticized feelings many urbanites had about rural life in the 1920s."18Suan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 24. The genre, while favored by many devoted listeners in rural areas, often proved equally appealing to the diverse, rapidly changing, and frequently fresh-off-the-farm urban populations.

For the early station owners in urban centers, the outstanding and unexpected response to country music offerings suggested that the power of their signal extended far beyond city limits. As cards and letters poured in from distant locales, broadcasters began to appreciate the extension of their influence.19Ibid, 23. Regionally- and soon, nationally-oriented barn dance broadcasts secured an even greater cultural significance as economic conditions worsened. Kristine M. McCusker suggests that, with the onset of the Depression, these programs held a powerful appeal for rural and working class people:

The barn dance radio genre . . . emerged just as many Americans sought relief from the rapid, confusing, and often frightening changes of the modern era. What began as regional entertainment . . . in the 1920s became a national phenomenon in the 1930s that capitalized on . . . [the] search for a meaningful, substantial life in a chaotic world.20Kristine M. McCusker, "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels": Women, Work and Barn Dance Radio, 1920-1960." (PhD dissertation: Indiana University, 2000), 20.

By the end of the thirties, barn dance programs appeared on stations across the country. According to one estimate, five thousand radio programs nationwide featured some form of county music during this period.21Jeffrey J. Lange, Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music's Struggle for Respectability, 1939-1954. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 28.

Somewhat paradoxically, as barn dance programs sprung up on new stations and moved across regional boundaries, they increasingly came to resemble one another. Certainly there were regional variations, but in most cases the shows retained a common formula. Richard Peterson provides a brief and simplified description of this standardization:

[The] format…dictated that there be variety from song to song in type, instrumentation, and personnel. In this context it was easy to insert informal banter among performers, humorous skits . . . and an increasing number of commercial advertisements. . . . The formula was based on Vaudeville—a quick succession of individuals and groups performing different sorts of music interspersed with comedy and informal banter between performers and the master of ceremonies . . .22Peterson, 99, 109.

|

| Grand Ole Opry souvenir program. |

Much of this similarity among programs stemmed from the frequent exchange of managerial staff and musical talent between stations.23Pecknold, 16. The most historically significant example of this early radio industry fluidity is the case of George D. Hay, the popular announcer on the National Barn Dance who, in 1925, was lured to Nashville's WSM. There he began the Saturday night WSM Barn Dance, an instantly successful program that, in 1927, was famously dubbed the Grand Ole Opry. While modeled on the Chicago program, Hay's Opry soon staked out its own identity and developed into the most successful, influential, and long-running of all barn dance programs.

The Grand Ole Opry's legacy is well-known. Bolstered by WSM's clear-channel status, and NBC network syndication in the early-1940s, the Opry displaced the National Barn Dance as America's favorite country music program. The show welcomed the biggest stars of country music and helped establish Nashville as the recognized home of the genre's developing industry. Hay shaped the Opry into the "most emphatically hillbilly of the major barn dances" by emphasizing southern stringbands and cornball comedy over the more genteel rural images found on other programs.24Ibid. As radio spread throughout rural America, listening to the Grand Ole Opry became an almost religious affair, with families gathered together each Saturday night. But, even as the Opry secured broadcast dominance, other barn dance programs continued to serve more distinctive regional tastes.

The Barn Dance in East Tennessee

As Nashville's Grand Ole Opry commanded attention on the increasingly nationalized airwaves, Knoxville fostered its own thriving radio environment. Two stations — WNOX and WROL — were at the heart of East Tennessee radio, and country music was, from the start, at the heart of their offerings. When Lowell Blanchard, a midwestern radio emcee, arrived at WNOX in 1936, Knoxville developed into a hotbed of country music programming and a center of innovation for the barn dance. Blanchard created and hosted the noontime Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round program, an instant and enduring success, and, later, the Saturday night Tennessee Barn Dance, a rival of the Opry. On WROL, country music programming also flourished, mostly under the sponsorship of the colorful local businessman Cas Walker.25Charles Wolfe, Tennessee Strings: The Story of Country Music in Tennessee. (Knoxville, TN: University of Knoxville Press, 1977), 83.

|

| Cas Walker event with Josh Graves (guitar), Monroe Queener (dobro) and crowd. |

As Nashville matured into country music's commercial center and WSM's Opry protected its spot on network airwaves, the city's output strove to appeal to a diverse national audience. In Knoxville, though, without such broad obligations, regional tastes flourished. In addition to the shows mentioned above, dozens of other country music programs benefited from the receptive regional atmosphere. Knoxville brimmed with local up-and-coming country music stars, many of whom, including Roy Acuff, Chet Atkins, Archie Campbell, and others, went on to greater success in Nashville and beyond. Unable to match Nashville's financial and geographical advantage, Knoxville's radio community instead developed into a training ground for the national country music industry.

According to historian Charles Wolfe, the audiences in Knoxville and the surrounding region also tended to prefer "more traditional, 'purer' forms of country music." As Nashville embraced newer and more progressive styles, the radio in Appalachian East Tennessee continued to reflect "the old styles and the old songs." By the mid-1940s, this meant hard-driving acoustic bluegrass music. Though the style was first heard in 1946 on the Opry and got its name and original sound from west-Kentuckian Bill Monroe, bluegrass resonated in central Appalachia, perhaps more so than anywhere else. This was due largely to the many Monroe followers and bluegrass pioneers, including Flatt and Scruggs, The Stanley Brothers, the Osborne Brothers, and dozens of others, who popularized the style on radio in Knoxville, East Tennessee, and throughout the Southern highlands.26Ibid, 83-85.

Following WWII, changing cultural circumstances caused a major shift in the development of the barn dance in East Tennessee and across the country. The FCC, after suspending new broadcast licenses during the war, started to actively encourage the growth of radio stations in less-populated areas. At the same time, young musicians returned home after serving in military, just as the popularity of the country style — a main source of relief and entertainment during wartime — continued to surge. For these emergent small-market stations, the availability of musicians and the continued success of the barn dance made live local country variety shows an ideal early programming format.

By the mid-1950s, though, with the emergent competition from television and the resulting increase in "formatted" radio stations, the success of the barn dance dwindled in larger metropolitan markets. By the late 1950s, the style, as a national phenomenon, had peaked in its live radio form. Most of the popular barn dance programs outside of the South were replaced by DJs spinning hit records. As an exception, the Opry, by then a bona fide American institution, persisted mainly on the strength of the powerful Nashville music industry and the city's growing tourism business. In Knoxville, the Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round ended in 1961 and the Tennessee Barn Dance, though broadcast in various forms into the 70s, lost much of its appeal and operated on much smaller scale.

Nevertheless, the surprisingly resilient barn dance genre evolved to fit the changing conditions. Successful television stations, especially those in the Southeast, boasted new "barn dance[s] with pictures."27Peterson, 232. Sponsors like Ralston Purina's Pet Milk, Chattanooga Medicine Company, and Martha White Flour began syndicating country music variety shows in television markets.28David Nusz Black, Television from a Third Coast: A History of Nashville Network and Syndicated Television Production: 1950-1983. (PhD Dissertation: The University of Tennessee, 1996), 393-394. Just as the early radio barn dance had popularized "hillbilly music" three decades earlier, these new visual renderings, including The Porter Wagoner Show, The Flatt and Scruggs Show, and the televised Grand Ole Opry extended the reach of country music farther into American popular culture. Alongside the larger nationally- and regionally-targeted programs, local variants also enjoyed success. In Knoxville and East Tennessee, well-loved homegrown programs like The Cas Walker Show, The Jim Walter Jubilee Starring Bonnie Lou and Buster, and Jim Clayton Startime, continued to foster a more distinctly regional barn dance idiom and atmosphere on television.

| Jim Clayton Startime: Jim Clayton, David West, Monroe Queener, and the Cider Mountain Boys, "Foggy Mountain Breakdown," early 1970s, Knoxville, Tennessee. Tennessee Archive of Moving Image and Sound: Jim Clayton Collection. |

During this same period, with television on the rise and older and entrenched radio stations relying heavily on formatting and recordings, small-town AM radio stations turned increasingly to localism as the top programming priority. Especially in Appalachia, the barn dance formula maintained a stable broadcast home on rural AM radio stations. In small-towns throughout East Tennessee, these programs provided a training ground for local musicians and allowed would-be country "stars" to sharpen their skills in the hope of landing a spot on Knoxville television, or, even better, earning a chance to move to Nashville, record an album, and play on the Opry. For the communities themselves, these barn dance programs were a meaningful display of resilient local culture and a broadcast setting in which to imagine the best about themselves and their values. One such small-town station was WLAF in LaFollette, Tennessee, and one such barn dance program was the Tennessee Jamboree.

LaFollette

|

| Map of LaFollette, Tennessee. (Base Map Data: US Census Bureau) |

The Tennessee Jamboree was created to entertain the residents of LaFollette and rural Campbell County in upper East Tennessee. Details of the area's history contribute to an understanding the character of the local community that helped shape, and, in turn, was aurally imagined on the Jamboree program. Located near the Powell River, LaFollette is surrounded to the north and west by the rugged Cumberland Mountains and to the south and east by fertile valley land and the Tennessee Valley Authority-developed Norris Lake. Unlike other towns in Campbell County, LaFollette's initial formation in the late 1800s was fully planned and developed through the efforts of outside business. Harvey M. LaFollette of Indiana, capitalizing on the abundant nearby coal and iron deposits, envisioned a massive industrial operation on the site. Starting with a land purchase of thirty thousand acres, he launched the LaFollette Coal, Iron and Railway Company in 1897. LaFollette's booming operation eventually included various coal mines, iron mines, coke ovens, railroads, and a blast furnace.

|

| Arthur Rothstein, People swim at lake created by Norris Dam, TN, 1942. |

During the first decades of the twentieth century, coal mining, along with timber and textile operations, dominated LaFollette's economy. Tobacco and livestock provided additional sources of income in the surrounding Campbell County farmlands. The area's prospects, like so many in central Appalachia, were prone to ebb and flow with the whims of political and business interests residing far beyond its borders. With the boom and bust of the coal and iron industries in the 1920s, LaFollette's fortunes suffered. The iron furnace officially closed in 1926. As the dominance of "King Coal" continued to wane, tourism-related industries emerged. The New Deal era construction of the Norris Dam, along with the TVA developed Norris and Cove Lakes, helped make Campbell County and LaFollette significant recreation destinations. In addition, the "Dixie Highway," a major roadway running between the South and the Midwest, from Florida to Chicago, became increasingly popular and brought a stream of motorists through the area.

|

| Arthur Rothstein, Man fishing at Norris Dam, TN, 1942. |

Like other coal towns, LaFollette's industries attracted a diverse population of eastern European immigrants and, especially, of African Americans in the early twentieth century. In the late 1800s, a "colored" high school opened in LaFollette that served, at its peak, nearly one hundred African American students from the Campbell County area. Howard "Louie Bluie" Armstrong, perhaps the most famous musician ever born in LaFollette, nurtured his abundant blues, jazz, and country fiddling skills within this rural African American community. Armstrong recorded several sides and played on major radio stations during the 1930s in Knoxville. As the coal boom declined, most non-white and European immigrant families moved out of rural Appalachia seeking better opportunities in the North and in major cities. The LaFollette Colored School closed in 1965 and today only a handful of African Americans still live in Campbell County. As with most all of the social and cultural institutions, local radio, when it came to LaFollette in 1953, remained segregated and operated principally to serve white residents. There is no existing evidence that members of Campbell County's black population were ever featured on WLAF or the Tennessee Jamboree program.

By the mid-1950s, as AM station WLAF began its early broadcasts, LaFollette had matured into a typical central Appalachian town. In 1957, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, in an attempt to assess a variety of pressing needs and problems, prepared "A Study of the Community of LaFollette, Tennessee." The study's language is straightforward and its assertions seemingly uncomplicated; but, taken as whole, it provides an ambivalent portrayal of life in mid-century LaFollette:

Mild climate, a natural setting, and moderate living costs make LaFollette an attractive community for living. It is a young and changing community. . . . LaFollette is a church-centered town; no plans involving community participation would be considered without consulting various church calendars. . . . [People surveyed] were of the opinion that LaFollette is a friendly place; they feel at home both in their neighborhoods and in the community as a whole. . . . The major problem in LaFollette is a lack of work opportunities for men. Too many have to go away from home to work. Half of the young men in LaFollette who complete high school must leave home in order to find work.29A Study of the Community of Lafollette, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archive. (Nashville: Public Libraries Division, 1957), 4-5.

Statistical information contributes to a more complicated and troubled picture. The median yearly income of LaFollette—$1,933—amounted to only roughly half of the national average of $3,709. The "educational level" also fell below the US standard, as well as Tennessee's.30Ibid, 50.

The "Social, Religious, and Recreational Life" section of the 1957 study revealed that churchgoing and visiting topped the list of pastimes. Recreation, including fishing and hunting, was popular. "Practically all" survey respondents confirmed owning a radio, and nearly three-fourths owned a television.31Ibid, 20. "Music" was the most popular radio program choice, including such particular shows as Cas Walker and the Mid-Day Merry Go-Round, both country music barn dance formats broadcast from Knoxville. "Hillbilly music" and the Grand Ole Opry also received mention. The television responses tended toward news and quiz programs. Radio, it seems, was increasingly a music-centered media — and in LaFollette, "hillbilly" was the music of choice.32Audio interview with Dolly Parton from American Routes. During an interview on American Routes, Parton talks about her musical and family roots in East Tennessee, and about singing on the Cas Walker Show. Available via http://americanroutes.wwno.org/.

WLAF

In the 1950s and 1960s LaFollette faced many social challenges. Economically, the area transformed from the unforgiving and exploitative industries of the past toward the unpredictable business opportunities of the future. The city bled young people in search of greater prospects elsewhere. Those who stayed and raised families, generation after generation, took comfort in the natural beauty, strong faith, and neighborly way of life. With the new AM station 1450 WLAF, residents of LaFollette finally had a station that worked hard to foster a sense of community. The barn dance format quickly found a home with the launch of the Tennessee Jamboree.

AM 1450 WLAF, LaFollette's first radio station, began broadcasting with 100 watts on Sunday, May 17th, 1953 at 2:00 pm. Before that, residents of LaFollette and Campbell County listened, as did most of rural America, to stations emanating from regional hubs in nearby, and sometimes distant, metropolitan areas. Though these commanding stations appealed to rural listeners, most people living outside the major population centers had not experienced local radio. LaFollette welcomed the new station with fanfare. The LaFollette Press listed local dignitaries in attendance for the first broadcast. As part of the opening ceremony, the Rev. John H. Thompson of the First Presbyterian Church gave an invocation and state politicians, including Senator Albert Gore Sr. and Representative Howard Baker, delivered greetings by way of transcription.

The mission of WLAF was, from the start, quite simple: give priority to the interests and events in its broadcast area. Bill Waddell, the station's current owner and its historian, has understood and maintained this locally-focused orientation since joining the station in the 1970s. His comments in 2005 reflect the attitude that shaped WLAF:

The station came on the air back in 1953 . . . to serve the community. We have still kept the local image. We do local news, local obituaries, [and a] local call-in trading show each day. We just kinda localize it. Forget about the rest of the world. If people want national news they've got CNN and all that. If they want full-time weather, they've got the Weather Channel. We just keep it locally of what's happening right here in our county, and it's worked pretty well for fifty-two years now…33Bill Waddell, taped interview by Joe DiCosimo, August 2005.

With dedication, WLAF has catered to the interests of LaFollette. "We do the local ball games . . . , we do the public commission meetings, the city council, the school board, and the county commission," adds Waddell. "It's just all local, like I say, everything we do is aimed at Campbell County. We just forget about the rest of the world. It works pretty well."34Ibid.

In addition, WLAF features the music and the musicians who affirm local preferences. "Lotta local talent around here, always has been," says Waddell. "Gospel and Bluegrass especially [are] extremely popular in this area. Here in the mountains. We're true mountain people."35Ibid.

Among the first programs launched on the WLAF airwaves was a Saturday night barn dance, the Tennessee Jamboree. As on so many of the other small-town post-war stations, country music proved a popular and reliable early staple. The appeal of the new program, coming from within the town's borders, cannot be underestimated. "That was the place to be on Saturday night, downtown LaFollette," Waddell recalls, "where some of the talented musicians from this area came and performed. It was an exciting time for everybody in LaFollette."36Waddell, reunion introduction. From tape of Louie Bluie Music and Arts Festival, Caryville, TN, 2007, from the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Listeners in LaFollette and Campbell Country were well-acquainted with the barn dance genre, either through WSM's Opry and network radio, or the Midday Merry-Go Round, the Tennessee Barn Dance, or Cas Walker from the stations in Knoxville. The power of radio and the success of these programs helped connect the residents of LaFollette with a growing sense of regional and national identity. But, with the new Tennessee Jamboree, LaFollette had a barn dance to make its own.

Tennessee Jamboree

From its earliest days in 1953, WLAF followed the models established by the national and regional stations of broadcasting live country music on Saturday nights. Unlike the news reports, sporting events, swap shops, and coverage of local government, the Saturday night programming transported listeners to an imaginary place created by talented LaFollette-area musicans and singers. The LaFollette country music variety show served as a crafted site for shaping and reinforcing "down home" values. That first Saturday night's Jamboree likely featured Monroe Queener, a well-known local dobro player with experience on WROL in Knoxville's Cas Walker show, and Ray Bolton, about whom we know little. Perhaps from the start, announcer Denny Walker began producing and hosting the Saturday night programs. Walker, a LaFollette native, had gained broadcasting and engineering experience in WWII. After helping launch WJJM in Lewisburg, Tennessee, in 1947, (where he had developed a barn dance program) he worked as an announcer and disc jockey at upstart WLAF. Under Walker's guidance, the Queener and Bolton program became a new show anchored by bluegrass band, the Blue Valley Boys.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Blue Valley Boys, LaFollette, Tennessee, early 1960s. |

Lead by guitarist Robert Stephens, this band included Arnold McNeely, Charlie Powers, and Fred Haggard, young men in their early 20s who had all grown up in Whitman Hollow outside LaFollette. According to Stephens, the band formed in response to a contest sponsored by the LaFollette Southern States Co-op Farm Store — the winning prize consisting of a trip to Bristol, Tennessee, for the opportunity to make a demo recording. Garnering the attention of Walker, the Blue Valley Boys landed the Saturday night spot on WLAF. Recorded in the station's basement, the show was likely the first to carry the Tennessee Jamboree name. The near-synonymous relationship between the Jamboree and the Blue Valley Boys was one that would last nearly twenty-five years.

The Tennessee Jamboree steadily gained popularity throughout the fifties, eventually outgrowing the small WLAF studio before moving to LaFollette's high school auditorium, where for the first time it was broadcast in front of a live audience. The lineup of the Blue Valley Boys experienced the first of several shakeups. By the late fifties, the group included local LaFollette musicians Henry Horne, Billy Ray Burge, Carlos Henderson, Monroe Queener, and Charlie Collins. Queener was well-known throughout East Tennessee for his influential bluegrass dobro style. Collins played fiddle in several regional bands, including the popular Pinnacle Mountain Boys of nearby Claiborne County. Robert Stephens, the original Blue Valley Boy, remained with the band and, at the urging of host Walker, took the role of group comedian. His simpleton persona "Slap Happy Jake" proved wildly popular and, with his stereotyped rural antics and exaggerated face makeup, linked the Jamboree to the legacy of medicine and minstrel show.

The show remained at LaFollette High into the early 60s and became "the place to be" for local LaFollette musicians. A changing assortment of talented pickers and singers joined the Blue Valley Boys on the Jamboree stage, including bass player, guitarist, and singer Red Harrison, and fiddler Dean Huddleston — both of whom had played with a southeastern Kentucky band called Pap and the Youngins, an ensemble that also sometimes included Collins and Queener. Collins and Harrison, as well as several other musicians later to join the Blue Valley Boys, also worked for what was locally dubbed the Big Shirt Factory, a major employer in the LaFollette area.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Blue Valley Boys, LaFollette, Tennessee, mid-1960s. |

|

| Elmer Longmire, LaFollette, Tennessee, mid-1960s. |

The most important addition to the Jamboree family during the early 60s was another Campbell County musician and Big Shirt Factory employee, Elmer Longmire, recruited by the Blue Valley Boys to not only take over the Jamboree, but also to manage and lead the band. Whether the Jamboree had fallen temporally on hard times, or perhaps had become too complicated to be produced informally from week to week is not clear. At around this time the multi-talented Longmire was also hired as station manager of WLAF, making him the natural successor to Denny Walker as the overseer and emcee of the Jamboree. In the recollections of Jamboree musicians, no person garners more praise and admiration than Longmire. War veteran, church leader, and family man, Longmire was revered in LaFollette.

|

| Charlie Collins and "Slap Happy" Cousin Jake |

Under Longmire's guidance the Tennessee Jamboree entered its peak period in the mid- to late 60s. After several years at LaFollette High, the program moved to the American Legion building where it attracted enthusiastic Saturday night audiences. The Blue Valley Boys personnel continued to change before settling into a more stable roster. The mid-60s version, often considered the classic lineup, included Longmire as emcee and rhythm guitarist; Red Harrison, bass and guitar; Robert Stephens, as comedian and alternating with Harrison on bass and guitar; Curt Caldwell, also alternating on guitar and bass; Dean Huddleston, fiddle; newcomer Carl Stump from Harriman, Tennessee, on mandolin; Monroe Queener, dobro; Carlos Henderson, banjo. After Henderson's death, L.C Edwards of LaFollette joined on banjo. All the Blue Valley Boys took turns on lead and backing vocals, with Longmire, Huddleston, and Stump forming an oft-featured trio.

Regular guest stars included Lois Johnson and Kirk Hansard, popular performers on Knoxville's Tennessee Barn Dance; Jim Fagan, a songwriter from nearby Clinton, Tennessee; and former Blue Valley Boy Charlie Collins and his whiz kid banjo protégé Larry McNeely, both members of another popular east Tennessee band, the Pinnacle Mountain Boys, and subsequently of Roy Acuff's Smokey Mountain Boys on the Grand Ole Opry.

|

| Kirk Hansard and Lois Johnson, Tennessee Jamboree, mid-1960s |

Over the years, the Jamboree featured regular "girl singers," sometimes causing Longmire to introduce the band as the Blue Valley Boys and Girls: Frances Boshears, Irene Lloyd and her daughter Sharon, Mary Madison, and Janice Patty. Barbara Sanders of LaFollette, known as "Little Barb" due to her diminutive size, served the longest of the girl singers, her boisterous voice and personality, as well as impromptu dance numbers with Longmire, making her one of the most popular Jamboree performers. Little Barb notwithstanding, the Jamboree was dominated by its male membership and by the traditional values of a patriarchal community. Though the "girl singers" were sometimes given prime spots within the program, none ever went beyond singing a couple of songs and then leaving the stage. No woman was ever an emcee or a featured instrumentalist. The Jamboree was markedly traditional, with the Boys always doing the musical "heavy lifting."

|

| Little Barb and Elmer Longmire,Tennessee Jamboree, mid-1960s |

Longmire, the Blue Valley Boys, Little Barb and the other "girl singers," and the regular guest stars, worked to make the Jamboree the aural "image" of a tight knit, family-friendly, and good-time-for-all local space. Not surprisingly, Longmire often welcomed the musician's children onto the stage to perform, all joining the Jamboree's country music community of the airwaves. In the late 60s, Longmire welcomed his wife Sara Miller and nephew Fred Longmire to the show. Hometown sponsors eagerly had their names and products pitched alongside LaFollette's talented pickers and singers. Wherever there was a parade, political rally, or summer concert in the park, you'd find the Blue Valley Boys and the Jamboree family.

An Original Broadcast, Part 1: Music

|

| Blue Valley Boys, LaFollette, Tennessee, 1969. |

The Tennessee Jamboree tapes probably should not exist. According to many Jamboree participants, the common practice in the late 1960s was to erase the content/s and reuse tapes as often as possible. At times during the Tennessee Jamboree's history, the program was recorded on Friday evenings and aired on Saturday night, allowing the Blue Valley Boys and Girls to travel and make money playing weekend events. In a continual recycling of tapes, programs were edited and rebroadcast on small AM stations in the nearby towns of Harriman and Wartburg. Fortunately, some musicians and radio employees valued these broadcasts and kept tapes for their home use. From these dispersed personal collections in basement or closet "archives" comes the current assortment of Jamboree tapes.

Historians have lamented the fleeting character of radio. While it shaped, reported, and reflected history, radio's means of doing so, its precious aural content/, often vanished as soon as it emerged — especially at small rural stations like WLAF where preservation was simply not a significant concern. The story of "Radio" that gets told tends to devalue the local and fixate on the national ambitions of big stations and large networks. Radio historian Michele Hilmes's observations are worth quoting at length:

Many — the vast majority — of broadcast hours are lost forever. What does exist tends to privilege the dominant and centralized sources . . . . Records and accounts of the larger and more successful stations, programs, and performers are more likely to survive than… those [of the] small stations providing a different service to a more marginalized audience, those programs deemed of specialized interest of least appeal whose scripts and records have long been destroyed, limited regional and local broadcasts, those efforts that never made it to realization precisely because they went against the grain of dominant practice. Much research needs to be done in lesser-known areas to bring them to other scholars' attention and to reflect more fully our diverse and conflicted media heritage.37Michele Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), xvi.

The Jamboree tapes, then, are not just significant to an esoteric interest in the history of LaFollette, or East Tennessee, or country music, or the barn dance; they contribute scarce and sonorous new evidence into a history of radio that more carefully addresses the "local" as something valued and persistent.

The tapes reveal the music, stage banter, and advertisements that marked the Tennessee Jamboree as a program rooted in and catering to an idealized local culture. The barn dance genre worked to create an imagined sense of collectivity and a nostalgic sense of rural values. Jody Berland describes the relationship between the aural medium and an imagined "community" evoked over the airwaves:

[T]he community that speaks and is spoken through [the] medium is . . . constituted by it, and is formed by its structures, selections, and strategies. . . . [R]adio comprise[s] an ideal instrument for collective self-construction, for the enactment of a community's oral and musical history. . . . [Radio] is oral, vernacular, immediate, transitory; its composite stream of music and speech . . . has the capacity to nourish local identity . . .38Jody Berland,"Radio Space and Industrial Time: The Case of Music Formats." In Canadian Music: Issues of Hegemony and Identity, eds. Beverly Diamond and Robert Witmer. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 1994), 175- 176, 181.

The Tennessee Jamboree must be understood in the broader context of the barn dance genre, and as exhibitive of the regional preferences of East Tennessee. At the same time, the Jamboree, as the tapes reveal, was crafted to the specific scale, social geography, and imagined character of LaFollette and Campbell County. To explore this assertion, I will look closely in this section at one of the surviving complete Tennessee Jamboree broadcasts. Representative of the entire collection of tapes, this broadcast, likely made in 1969, provides an accurate example of the style and format employed on the Jamboree throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

From the first moments of the opening musical number — a spirited instrumental arrangement of the traditional tune "John Hardy" featuring the quick-picking of L. C. Edwards on banjo and Monroe Queener on dobro — it is clear that the Tennessee Jamboree is a fast-paced affair. Over the course of the hour, the Blue Valley Boys and Girls, led by Elmer Longmire, managed to squeeze in seventeen musical selections. In accordance with the barn dance formula, the songs are very different from each other and feature varying instrumental soloists, lead vocalists, and shifting arrangements. Unlike the nationally prominent programs with their sprawling roster of performers, the Jamboree's entire workload is carried by the Blue Valley Boys and Girls.

The Jamboree's musical diversity stems from the ability of the group to move among styles and settings. Calling the Blue Valley Boys and Girls a bluegrass band does not do justice to their performances. East Tennessee radio audiences preferred more "traditional" sounds. Bluegrass, with its old-time roots and conservative aura — although it was not much older than rock and roll — proved a favored style in the region even as other forms of popular and country music dominated the airwaves and record sales elsewhere. Even so, the Blue Valley Boys and Girls, working in a bluegrass idiom, with an entirely acoustic instrumentation and heavy emphasis on "hot licks" and high harmonies, did not strictly adhere to the standard repertoire of the genre.

The seventeen songs performed on this particular broadcast included bluegrass standards, banjo instrumentals, faux-ethnic dobro numbers, harmony-rich hymns, sentimental vocal trios, cowboy songs, novelty songs, and classic country ballads. Throughout the program, as songs were introduced, Longmire mentioned the requests elicited, stamping this assortment as belonging to the tastes of an actively engaged audience. In taking on such a variety of material, Longmire and the band made a broader statement as well. Though the Blue Valley Boys and Girls performed frequently in and around LaFollette and Campbell County, the audience knew that the musicians maintained day jobs. While the national country music industry increasingly "discovered its best interests . . . in a package with clouded identity, possessing no regional traits," the Blue Valley Boys and Girls demonstrated that they could play in any country sub-style while their everyday lives infused the material with local integrity.39Bill C. Malone, Country Music, U.S.A. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 369.

Emcee Elmer Longmire varied the show's musical content/s by creatively exploiting the distinctive talents of the Blue Valley Boys and Girls, giving the impression of a much larger roster. Most members of the group filled multiple roles during the hour. Longmire, as emcee, pitchman, bandleader, director, and stage manager, also performed as tenor vocalist in the Jamboree's trio. Alongside Sara Miller, the requisite "girl singer," and guitarist Fred Longmire, the full-voiced elder Longmire performed throughout on a wide range of material. Just after the show's introduction, the trio launched into rollicking rendition of bluegrass favorite "Roll, Muddy, River." A few minutes later, they led the group through adaptations of classic country hits "Just Before Dawn" and "You'll Always Be My Blue-Eyed Darling." When the time came to cover the cowboy song "Way Out There," and the hymns "The Holy Hill" and "Nearer My God to Thee," the trio again guided the ensemble.

Bassist Red Harrison, when leaving his position as the solid foundation of the ensemble, often moved to the forefront and performed as the Jamboree's most skilled solo singer. His rich baritone voice, on par with some of the finest country singers of the day, was featured on the sentimental ballads "Just Before Dawn," "Today I Burned Your Old Love Letters," "Its Not Love, But Its Not Bad," and several others. Never mere sidemen, banjo player Edwards and dobro player Queener, though not showcased as vocalists, also moved between group supporting roles and featured instrumental soloists. Their playing secured the vibrancy of the group's acoustic sounds, and their solos added the standard breakdown instrumentals.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Elmer Longmire and Red Harrison |

Edwards' participation on this program provided an even greater localizing function. Though all the members of the Blue Valley Boys and Girls lived in or near LaFollette, Longmire singled out Edwards in representing the real connection to "his own people":

Elmer: All right, we better get Sidro [L.C.] now up on the banjo. We get a lot of requests here, especially from his own people here, wants to hear him pick. Come on up there, Sid, and let's do a little bit of pickin' here. I always like to get you off-guard ‘cause . . . you pick better when I get you off-guard like that.

L.C.: You sure keep me off-guard.

Elmer: What are you gonna play for us, son?

L.C.: Let's do some "Lost Creek."

Elmer: I've always wanted to hear that one.

Edwards' "Lost Creek," a banjo instrumental, is the only song on this broadcast with local origins. Lorne Rogers, the tune's composer, was an influential banjo player in the Pinnacle Mountain Boys, another well-loved local bluegrass band heard frequently during the and late 1950s early 1960s on East Tennessee radio. "Lost Creek" would very likely have been recognizable as a local favorite. Rogers was the primary inspiration and influence for Edwards's own musical career. After Rogers' death in a car accident in the early 1960s, Edwards continued to play the piece quite regularly on the Jamboree.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, L.C. Edwards and Monroe Queener, LaFollette, Tennessee, 1968. |

Week after week, year after year, broadcasting to a city and county of farmers, miners, textile workers, and their families, the Tennessee Jamboree, shaped by hard-working and resourceful local musicians playing hard-driving, sentimental, and sacred favorites, produced the idealized spirit of LaFollette.

An Original Broadcast, Part 2: Advertising and Banter

Along with music, other elements within the Tennessee Jamboree broadcast promoted and projected LaFollette and Campbell County. Advertisements of local businesses were heard repeatedly over the Jamboree hour, connecting the barn dance fantasy with economic and social geography. Host Elmer Longmire delivered promotional spots with charm and finesse. Sponsorship, as was common on AM radio, came from local businesses. For the Jamboree these included the area grocery market, music store, tire outlet, and electrical service. Never overly commercial, the promotional moments, as in the example below, were woven into the character of the Jamboree:

Don't forget now, with this cold weather that's going to bring on the snow tires, friends. ... We hope you folks remember now the folks out at Burcham Tires here in LaFollette. They've got those snow tires, friends, recaps right now, $10.95. So get out and see 'em. Of course there's from 37 to 52 cents federal excise tax. A recappable tire too. And if you're going to need snow tires, get by and see the folks at Burcham. Remember you get a new tire guarantee with them too when you buy 'em at Burcham, right here Highway 25W south of LaFollette.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Blue Valley Boys, 1968. |

These informal advertisements paid for the Jamboree's weekly operation and anchored the program in place. Another advertising example, while drawing the nearby town of Jacksboro onto the Jamboree map, had an even greater community-focused intent. Many residents from Campbell County trekked to Knoxville and other larger cities in the area to complete the bulk of their shopping at supermarkets and chain stores.40A Study of the Community of Lafollette, Tennessee, 5. Notice how Longmire tailors his small-town pitch:

Now remember our good friends down at Jacksboro. Don Nance's Big Gulf Station, of course, and Richardson's Grocery . . . , located over at Jacksboro Station. And you know friends, we've often said that, it's not always the big things that count a lot of time, because Richardson grocery is one of your nicer little markets. You'll find just about everything there that you'll find in any of the other supermarkets. And you'll also find it at competitive prices too. So tell 'em we sent you by from the Tennessee Jamboree. . . .

Longmire, as manager of the radio station and previously as an employee in the local shirt factory, could deliver the promotions with persuasive confidence, intimate knowledge, and seemingly authentic intentions:

Friends, remember now our good buddy Howard White Electrical Service. . . . Anytime you need any electrical work done at all you call him up and they'll be happy to come out and give you a free estimate on any house you want wired, any repairin' or remodelin' or anything like that, without any obligation. They'll be happy to give you a free estimate on exactly what it'll cost you to get the job done. Friends, you don't have to worry about it passin' inspection when the boys at Howard White Electrical Service do it, because they've always passed inspection right off the bat . . .

The music and promotional announcements were packaged within a jocular atmosphere and banter-filled collaboration, with the musicians and Longmire creating an on-air community aimed at the imagined listening one. Longmire orchestrated this general atmosphere from the primary microphone, directing a swift flow of ribbing and self-deprecating commentary back and forth between band members. He tagged certain musicians with playful nicknames that cast them in much the same spirit as the stock characters of the traditional barn dance. With bass player and singer Red Harrison, Longmire created the affable "Big Red," and for banjo player L.C. Edwards, the mischievous "Ol' Sidro."

|

| Tennessee Jamboree, Blue Valley Boys, LaFollette, Tennessee, mid-1960s. |

On this particular broadcast, Edwards — Ol' Sidro — nearly brings the show to a standstill with his antics. At some point, of course not seen by listeners, Edwards donned a sombrero to interfere with the playing of his bandmates. After the song was completed, Longmire explained the situation:

Longmire: Seems like I'm having a lot of trouble with my group here tonight . . . I tell you what we have a lot of fun . . . Well, friends, for you folks that don't have television, or radio vision, whatever it is, L.C.'s got one of the awfulest looking hats here that I have ever seen. And I don't know where he got it. He musta got it out there on the creek someplace. He just got through playin "Lost Creek." . . . Those of you who just tuned in, we're not drunk, sure. That hat that L.C. Edwards had on started the whole thing off. That throwed everybody off. I never seen no such a hat in my life. Where'd you get that Sid-Ro? . . .

Edwards: I'm putting it back, they's somethin' a crawlin in it.

Longmire: We hope we got through it enough that you folks out there a-listenin' could understand it anyway.

Humor also minimized the effect of any less-than-perfect performance. Unlike the creators of the big city barn dance shows who worked to rusticate their slick and seamless programs, those of the Tennessee Jamboree were not afraid or, perhaps due to their low-budget circumstances, able to cover up mistakes. The Blue Valley Boys and Girls took these missteps in stride and let the audience in on the fun and unpredictability of live performance. The following exchange, starting before the final chord has even fully decayed, comes after Longmire had struggled with certain passages in "Then I'll Stop Loving You":

Elmer: Well, we didn't miss that in over forty-seven times I don't believe. But I hope we got through it enough to where it's . . .

Red: That's all right Elmer, I took care of you buddy.

Elmer: Why . . . Red I knew you'd do it. We can always count on Red bailing us out when we miss something like that.

Listening to the tape, I hear these unreserved moments as a successful attempt at fostering an aural intimacy with the listening audience. "[I]t falls to the DJ's voice to provide an index of radio as a live and local medium," observes Jody Berland, "to provide immediate evidence of the efficacy of its listener's desires. It is through that voice that the community hears itself constructed, through that voice that radio assumes authorship of the community, woven into itself through its jokes [and] advertisements, all represented, recurrently and powerfully, as the map of local life."41Berland, 185. Though Berland writes of the radio disc jockey, I believe her comments are more applicable to the performers in the barn dance setting and their good-natured back and forth.

The humor of the Tennessee Jamboree emerged from and was directed toward the idealized local character. The chatter was recognizable as derivative of the larger barn dance genre, but was reinvigorated here in the particular voices and personas of musicians and entertainers born and raised in Campbell County. The Blue Valley Boys and Girls, if not literally acquainted with the listening audience (and in many cases, they were), certainly were familiar types to them. These radio performers worked to create an atmosphere as familiar as that found in any home or porch for an evening of music-making. Unlike the stars in Nashville, or even Knoxville, for those performers on the Tennessee Jamboree, this familiarity was not a stretch. Just as the music brought the barn dance down to local scale, and, just as the advertisements — promoting nearby businesses — grafted the place and space of the town into the program, so too did the natural and friendly banter affirm a romanticized social spirit of an imagined LaFollette listening community.

"Our time has come and gone"

Boys, I'll tell ya what, our time has come and gone looks like. We've had a good time here on the Jamboree friends, hope you've enjoyed it. Don't forget our fine sponsors brings you the Jamboree . . . here on Saturday night. We've had a nice time friends. You have a nice weekend. We'll see you again next Saturday night on the big Tennessee Jamboree! ---Elmer Longmire

Fieldwork and research efforts continue on the Tennessee Jamboree project. There are more stories to tell, talents to reveal, and pieces to fit into a puzzle that is the program's character, history, and legacy. I have tried to resituate the Tennessee Jamboree in the expressive life of LaFollette and Campbell County, in the broad sweep of musical activity in the region, and in the incomplete chronicle of the barn dance. Radio was, and to certain extent continues to be, an integral part of life in rural and small-town America. More than any other modernizing technology, radio moved so-called isolated areas closer to the US mainstream. But, even with the transformation toward a new "national" identity, there also emerged a complicated and perseverant notion of the "local." As the large national broadcast services quickly consolidated and offered "homogenous, rather than differentiated" programming, small local stations worked to fill this void, and, in doing so, to fulfill the early promise of diversity within the radio medium.42Smulyan, 32. The barn dance was one early and long-running favorite. The seemingly contradictory and irreconcilable national barn dance formula — with its rural representation via a mass medium, its sense of place on a place-defying technology, and its promotion of nostalgia in a world of the future — proved viable for many years across disparate scales and settings. While the National Barn Dance and the Grand Ole Opry were able to draw on local, regional, and ethnic musical traditions to craft a national entertainment format, programs like the Tennessee Jamboree readapted and readopted "country music" and the barn dance genre into a platform for thoroughly local expression.

|

| Tennessee Jamboree reunion at the Louie Bluie Music and Arts Festival, Caryville, Tennessee, June 2007. |

The Tennessee Jamboree is but one of dozens, perhaps hundreds, of similar programs that made their way into US homes and lives. The program showcased the best in homegrown talent and brought the barn dance genre to the truly local scale. With its music, banter, advertisements, and atmosphere, the program reflected and imagined LaFollette and Campbell County, Tennessee, over the airwaves. Without the Tennessee Jamboree tapes, the program would be revered and remembered, but only by those who experienced it. With the discovery of these broadcasts, the Jamboree can be relived and appreciated as a testament to the vitality of local radio and local culture.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express a deep gratitude to all of the Blue Valley Boys and Girls, and their families, who shared with me their time, memories, and personal "archives," including Frances Boshears, Curt Caldwell, Charlie Collins, L.C. Edwards, Red Harrison, Dean Huddleston, John Hunley, Lois Johnson, Fred Longmire, Doris Queener, Barb Sanders, Robert Stephens, and Carl Stump. I would also like to thank the members of the Cumberland Trail History and Archive team, especially our leader Bob Fulcher, Brian Vollmer, Allison Williams, Linda Dougherty, Jim Brannon, Jennifer Macasek, Leslie Smith, Brooke Bradley, and Ajay Kalra. My sincere appreciation as well to Bradley Reeves at the Tennessee Archive of the Moving Image and Sound for preserving so many treasures and for sharing some of them with me in this current effort. Many thanks also to Susan Smulyan at Brown University for helping shape this project from the very start, and to Franky Abbott, Allen Tullos, and Sarah Toton at Southern Spaces for dedicating so much effort and wisdom to its completion.

About the Author

Bradley Hanson is currently a PhD student in ethnomusicology at Brown University. During summers he helps lead an ongoing project of the Tennessee State Parks to collect, archive, and present the music, folklore, and cultural history of the eleven counties along the 300-mile Cumberland Trail State Scenic Trail corridor.

Recommended Resources

Primary Sources

A Study of the Community of Lafollette, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archive. Nashville: Public Libraries Division, 1957.

Tennessee Jamboree Recordings. Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville and Caryville, Tennessee.

The L.C Edwards Tennessee Jamboree Audio Collection

The Queener Tennessee Jamboree Audio Collection

The Fred Longmire Tennessee Jamboree Audio Collection

The Carl Stump Tennessee Jamboree Audio Collection

Interviews:

Bill Waddell, August 2005, with Joe DiCosimo.

Charlie Collins, June 2007, with Leslie Smith.

L.C. Edwards, July 2007, with Bradley Hanson and Jennifer Macasek.

John Hunley; Red Harrison; Doris Queener; Carl Stump; Barbara Sanders; Frances Boshears; July 2008 with Bradley Hanson.

Dean Huddleston, August 2008, with Bradley Hanson and Brian Vollmer.

Fred Longmire; Lois Johnson; Robert Stephens; August 2008 with Bradley Hanson.

Print Materials

Berland, Jody. "Radio Space and Industrial Time: The Case of Music Formats." Canadian Music: Issues of Hegemony and Identity. Eds. Beverly Diamond and Robert Witmer. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 1994.

Berry, Chad (ed.) The Hayloft Gang: The Story of the National Barn Dance. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Black, David Nusz. "Television from a Third Coast: A History of Nashville Network and Syndicated Television Production: 1950-1983." University of Tennessee, PhD dissertation, 1996.

Daniel, Wayne W. Pickin' on Peachtree: A History of Country Music in Atlanta, Georgia. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Doerksen, Clifford John. American Babel: Rogue Radio Broadcasters of the Jazz Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Douglas, Susan J. Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Fornatale, Peter, and Joshua E. Mills. Radio in the Television Age. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1980.

Hilmes, Michele. Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Howard, Herbert H. "Country Music Radio Part 1: The Tale of Two Cities." Journal of Radio and Audio Media 1.1 (1992): 105-112.

Kline, Ronald R. Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

"LaFollette Radio Station on Air, Dedicated Sunday." The LaFollette Press. May 21, 1953.

Laird, Tracey E. W. Louisiana Hayride: Radio and Roots Music Along the Red River. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lange, Jeffrey J. Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music's Struggle for Respectability, 1939-1954. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

"Like Country Style Music? Tennessee Jamboree Has It Each Saturday Night." The LaFollette Press. March 15, 1965.

Lornell, Kip. "Early Country Music and the Mass Media in Roanoke, Virginia." American Music 5.2 (1987): 403-416.

Mallard, Kina S. "Country Music Part II: The Mid-Day Merry-Go-Round." Journal of Radio and Audio Media 1.1 (1992): 113-120.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music, U.S.A. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985.

McCusker, Kristine M. "'It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels': Women, Work and Barn Dance Radio, 1920-1960." PhD dissertation, Indiana University, 2000.

McIntosh, Heather. "Music Video Forerunners in Early Television Programming: A Look at WCPO-TV's Innovations and Contributions in the 1950s." Popular Music and Society 27.3 (2004): 259-272.

Pecknold, Diane. The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Peterson, Richard A. Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Podber, Jacob J. "The Electronic Front Porch: An Oral History of the Early Effects of Radio, Television, and the Internet on Appalachia and the Melungeon Community." PhD dissertation, Ohio University, 2001.

Pruett, David B. "Preserving Cultural Identity: WPAQ Radio and the Dissemination of Bluegrass and Old-Time Music." M.M. thesis, Florida State University, 2000.

Pusateri, C. Joseph. Enterprise in Radio: WWL and the Business of Broadcasting in America. Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1980.

Smulyan, Susan. Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994.

Smyth, William J. "Traditional Humor on Knoxville Country Radio Entertainment Shows." PhD dissertation, University of California-Los Angeles, 1987.

Tribe, Ivan M. 1996. Mountaineer Jamboree: Country Music in West Virginia. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996.

Wolfe, Charles. Tennessee Strings: The Story of Country Music in Tennessee. Knoxville, TN: University of Knoxville Press, 1977.

Links

American Folklife Center, US Library of Congress

http://www.loc.gov/folklife/

American Roots Music, PBS Series

http://www.pbs.org/americanrootsmusic/index.html

Country Music Hall of Fame

http://www.countrymusichalloffame.org/

Hillbilly-Music.com - Home of Old-Time Country Music

http://www.hillbilly-music.com/

History of the Opry, Opry.com

http://www.opry.com/about/History.html

Old Time Music Homepage

http://www.oldtimemusic.com/index.html

Radio Lovers.com, National Barn Dance

http://www.radiolovers.com/pages/nationalbarndance.htm

Roughstock’s History of Country Music

http://www.roughstock.com/history/index.html

University of North Carolina Music Library

http://www.lib.unc.edu/music/

| 1. | Susan Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 57. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ibid, 79. |

| 3. | Ronald R. Kline, Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America. (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 10. |

| 4. | Ibid. |

| 5. | Ibid, 116. |

| 6. | Ibid, 287. |

| 7. | Joseph C. Pusateri, Enterprise in Radio: WWL and the Business of Broadcasting in America. (Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1980), 153. |

| 8. | Douglas, 5. |

| 9. | Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 97. |

| 10. | Kline, 287. |

| 11. | Jacob J. Podber, "The Electronic Front Porch: An Oral History of the Early Effects of Radio, Television, and the Internet on Appalachia and the Melungeon Community." (PhD dissertation: Ohio University, 2001), 121. |

| 12. | Ibid, 143-144. |

| 13. | Ibid, 132-133. |

| 14. | Pusateri, 221. |

| 15. | Ibid. |

| 16. | Diane Pecknold, The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 15. |

| 17. | Ibid, 16. |

| 18. | Suan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 24. |

| 19. | Ibid, 23. |

| 20. | Kristine M. McCusker, "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels": Women, Work and Barn Dance Radio, 1920-1960." (PhD dissertation: Indiana University, 2000), 20. |

| 21. | Jeffrey J. Lange, Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music's Struggle for Respectability, 1939-1954. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 28. |

| 22. | Peterson, 99, 109. |

| 23. | Pecknold, 16. |

| 24. | Ibid. |

| 25. | Charles Wolfe, Tennessee Strings: The Story of Country Music in Tennessee. (Knoxville, TN: University of Knoxville Press, 1977), 83. |

| 26. | Ibid, 83-85. |

| 27. | Peterson, 232. |

| 28. | David Nusz Black, Television from a Third Coast: A History of Nashville Network and Syndicated Television Production: 1950-1983. (PhD Dissertation: The University of Tennessee, 1996), 393-394. |

| 29. | A Study of the Community of Lafollette, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archive. (Nashville: Public Libraries Division, 1957), 4-5. |

| 30. | Ibid, 50. |

| 31. | Ibid, 20. |

| 32. | Audio interview with Dolly Parton from American Routes. During an interview on American Routes, Parton talks about her musical and family roots in East Tennessee, and about singing on the Cas Walker Show. Available via http://americanroutes.wwno.org/. |

| 33. | Bill Waddell, taped interview by Joe DiCosimo, August 2005. |

| 34. | Ibid. |

| 35. | Ibid. |

| 36. | Waddell, reunion introduction. From tape of Louie Bluie Music and Arts Festival, Caryville, TN, 2007, from the Tennessee State Library and Archives. |

| 37. | Michele Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), xvi. |

| 38. | Jody Berland,"Radio Space and Industrial Time: The Case of Music Formats." In Canadian Music: Issues of Hegemony and Identity, eds. Beverly Diamond and Robert Witmer. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press, 1994), 175- 176, 181. |

| 39. | Bill C. Malone, Country Music, U.S.A. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 369. |

| 40. | A Study of the Community of Lafollette, Tennessee, 5. |

| 41. | Berland, 185. |

| 42. | Smulyan, 32. |