Overview

Allen Tullos considers the shifting political meanings of Alabama's Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Essay

In one of the stranger scenes of this year's presidential campaign marathon, a dozen Gees Bend quilters joined hands with candidate John McCain, singing "Old Ship of Zion" as they ferried across the Alabama River in the rural Black Belt. The quilters, known for their spectacular, handmade textile art exhibited in museums from New York to Houston to Atlanta, lent a gracious moment of local color to the candidate's "Forgotten Places" tour. Quilter Mary Lee Bendolph, aged seventy-two, told a reporter that McCain had "touched her heart" by visiting this region that includes counties with some of the highest rates of poverty and highest percentages of Democratic voters in the United States. "I truly thank him for coming. It was wonderful to meet him, but no, I think another has my vote."1Charles J. Dean, "In Black Belt, McCain Wins Hearts, Not Votes," Birmingham News, April 22, 2008.

|

| Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama. |

Earlier that day, upriver in Selma, with the Edmund Pettus Bridge as skeletal backdrop, McCain had spoken to a small, heavily white gathering, announcing that he would be "the president of all the people." But most of the people in this seventy-percent African American city demonstrated their solidarity by staying away. "McCain's policies unify us," said lawyer and longtime civil-rights activist Faya Rose Touré. "That's why you don't see black people here."2Phillip Rawls, "McCain Takes GOP Campaign into Rural Alabama Democratic Turf," Associated Press, April 21, 2008; Charles J. Dean, "McCain Visits Gees Bend Quilters," Birmingham News, April 21, 2008.

Besides the Black Belt gig, a T-shirt for the Forgotten Places Tour would have read: Appalachia; Youngstown, Ohio; and New Orleans's Ninth Ward—locations to be checked off in early spring before the campaign turned serious.

Selma and the Pettus Bridge signify victories by a people in a place forgotten since the mid-1960s by the GOP, except when persecuting voting rights activists. With McCain's dismal civil rights record throughout years in Congress, including his (later retracted) opposition to the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday, a lot of water has passed under his bridge, and a lot of other stuff too. Still, there stood the senator on the Selma riverbank, "framed in camera shots by the bridge where white police officers beat black demonstrators trying to march to Montgomery in 1965," wrote Elisabeth Bumiller of the New York Times, "and where Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama converged last year in a political spectacle to commemorate the footsteps of the marchers."3Elisabeth Bumiller, "On McCain Tour, a Promise to Find 'Forgotten' America," New York Times, April 22, 2008. The Bloody Sunday beatings, by Dallas County deputies and Alabama state troopers, provoked international outrage, led to the Selma to Montgomery March, and gave rise to the national clamor that assured the Voting Rights Act became law.

|

| Aerial view of marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, 1965. |

Since 1965, the Edmund Pettus Bridge has taken on the meanings and features of a venerated public place. Twenty-year and twenty-five-year anniversary reenactments drew widely-scattered veterans of the original events back to Selma. In 1996, Congress created the Selma to Montgomery National Voting Rights Trail along once-contested terrain. Historians gathered oral histories and wrote books. Local activists began museums and commemorative parks where the bridge touched either side of the Alabama River. And since the early 1990s, the "spectacle" of an annual Bridge Crossing Commemoration has become a tourist destination and an authenticating ritual for politicians of various stripes seeking to reaffirm or newly signal their ties to the meanings evoked by what is now one of the country's most well-known structures.4Alvin Benn, "Historic Edmund Pettus Bridge Brings Fame, Fortune, to Selma," Montgomery Advertiser, January 5, 1992.

Binding memories to landscape, the bridge at Selma locates transitions from one time and space to another. Named for Edmund Pettus, Confederate brigadier general and post-Reconstruction, white-supremacist US Senator from Alabama, the landmark bridge was finished in 1940, the heyday of Jim Crow. In March 1965 it became not just a means of getting from one side of the river to the other, but a site where a people crossed out of repressive racial territory and into a social geography that they were remaking to suit themselves. In annual Bridge Crossing speeches, the Alabama River often becomes the Jordan or the Red Sea, watery passageways leading to freedom.

As the Bridge Crossing has grown in attendance and visibility, a diverse cast of civil rights, religious, and political figures, musicians and media celebrities, have walked the walk. In 2000, President Bill Clinton and Coretta Scott King led a thirty-fifth anniversary crowd of twenty thousand. Urging celebrants to "look at the South on the other side of the bridge," Jesse Jackson in 2003 warned against nostalgia, against resting on laurels and letting the memorial rituals displace present-day activism: "Beyond the bridge is crippling poverty, people working without fair wages."5Jannell McGrew, "Discrimination Still Alive, Jackson Says," Montgomery Advertiser, March 10, 2003. In 2005, the Bridge Crossing celebrated "Invisible Giants," unsung worthies who tilled the grassroots and filled the ranks of marchers, but went largely unmentioned in popular accounts. This year, representative John Lewis (who always brings along a congressional delegation), and the reverends Jackson and Al Sharpton were the headliners. "I don't think it really matters who shows up to speak," said Sam Walker, a Bridge Crossing organizer, "because this thing is bigger than any of us. It just keeps getting bigger each year."6Alvin Benn, "Return to Selma," Montgomery Advertiser, March 10, 2008.

The presidential campaign implications of the 2007 Bridge Crossing set the bar high with empathetic allusions and aspirational bonds. Addressing a mostly black audience at First Baptist Church before setting foot on the Pettus Bridge, Hillary Clinton shifted into the kind of exaggerated drawl that falls painfully on the ears before leaping to YouTube. Reciting gospel lyrics familiar to fans of James Cleveland, she spoke in what trollish critics pounced upon as her "black-cent": "I want to begin by giving praise to the almighty. I don't feel no ways tired. I come too far from where I started from. Nobody told me that the road would be easy."7Michelle Malkin, "Queen of Cringe," New York Post, April 25, 2007; "The Big Story with John Gibson," Fox News Network, March 5, 2007. Straining to speak in the voice of the Bridge, Senator Clinton's affirmation of endurance and persistence—"the march is not over"—became a moment of unintended caricature.8Dahleen Glanton and Mike Dorning, "Clinton, Obama Commemorate Selma Anniversary," Chicago Tribune, March 4, 2007.

Also on hand that day in 2007 was Bill Clinton, deciding at the last moment to show up for induction into Selma's Voting Rights Hall of Fame, but who seems largely to have made the trip as a mission of campaign bridge building. The Clinton whom Toni Morrison had called the nation's "first Black President" sought to parlay his popularity among African Americans into momentum for Hillary.9For Toni Morrison's comment see Wikipedia, s.v. "Toni Morrison," accessed May 6, 2008, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toni_Morrison. Yet, before another year had passed, John Lewis, the standard for courage and constancy, would first support Hillary, then switch to Barack Obama. For Hillary, observed an NPR commentator about this latest "battle of Selma," it's "almost like she's running against a younger, blacker version of her own husband."10Robert George on "News and Notes," National Public Radio, March 5, 2007. The spirit of the Bridge was shifting, away from past alliances, toward a possibility unimagined at the last Bloody Sunday anniversary.

|

| Video: At the 2007 Bridge Crossing Commemoration in Selma. |

"If it hadn't been for Selma, I wouldn't be here," Barack Obama said to attendees (some wearing "Alobama" T-shirts) of a prayer breakfast that same March morning in 2007. "This is the site of my conception. I am the fruits of your labor. I am the offspring of the movement. When people ask me if I've been to Selma before, I tell them I'm coming home."11Nedra Pickler, "In Selma, Obama Appeals to Black Voters," Associated Press, March 4, 2007; Tom Baldwin, "Quest for Black Vote brings Obama and Clinton to Heart of Old South," Times (London), March 5, 2007.

Later that day, before joining Bill and Hillary and thousands of others for the Crossing, Obama spoke at Brown Chapel AME Church, one of the most important civil rights rallying spots of the 1960s and the starting point for the original Selma March. The senator from Illinois told how, during the Kennedy administration, his Kenyan father benefited from an education program in Hawaii where he met Obama's mother, a white student from Kansas. "There was something stirring across the country because of what happened in Selma, Alabama," he said, "because some folks are willing to march across a bridge. So they got together and Barack Obama, Jr., was born." Lest reporters and bloggers think that here was a gotcha moment, a campaign spokesman quickly pointed out that Barack Junior, born in 1961, more than three years before the March, was "speaking metaphorically about the civil rights movement as a whole." A fact-obsessed family history misses the meaning in Obama's appropriation of the Pettus Bridge for the work of what he calls the "Joshua generation"—as contrasted with the civil rights veterans' "Moses generation." "We've got to remember now that Joshua still has a job to do," he said. "There are still battles that need to be fought; some rivers that need to be crossed."12Glanton and Dorning; "Sen. Obama Delivers Remarks at a Selma Voting Rights March Commemoration," as released by the Obama Campaign, March 4, 2007.

More than a year after the Selma prayer breakfast and his Brown Chapel speech, as Obama claimed the requisite delegates to become the Democratic nominee, he offered a cheering St. Paul, Minnesota, crowd a list of actors and moments through which, "every so often," compassionate people in particular places call upon their "fundamental goodness to make this country great again:" "that band of patriots in Philadelphia hall" who declared for a more perfect union; "all those who gave on the fields of Gettysburg and Antietam their last full measure of devotion" to save the union; the "greatest generation" of World War II; "the workers who stood out on the picket lines; the women who shattered glass ceilings"; and "the children who braved a Selma bridge for freedom's cause."13"Text of Democrat Barack Obama's Prepared Remarks for a Rally on Tuesday in St. Paul, Minn., as Released by his Campaign," Associated Press, June 4, 2008.

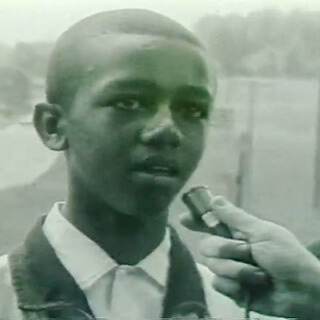

Children amid Bloody Sunday? Children (more accurately teens and youth) are usually linked in the freedom struggle imaginary not to Selma but to Birmingham's Children's Crusade in 1963, where they strategically provoked Bull Connor's overreaction, where they were hosed and chased by police dogs, watched by the world.14Selma native Joanne Bland, later a co-founder and director of the National Voting Rights Museum, was eleven years old when she and her fourteen-year-old sister Linda participated in the Bloody Sunday events. See "

Obama's joining of the Children's Crusade with the troopers' assault upon the six hundred at the Selma Bridge was much like the factually impossible, but figuratively crucial story of his conception—"because some folks are willing to march across a bridge." It reveals the hoped-for trajectory of a new generation coming to political age after the long season of reaction that followed the gains of, and shaped the resistance to, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Obama's inclusive narratives of himself as a child of the Selma Bridge, and of "the children who braved a Selma bridge for freedom's cause" re-place a venerable—if increasingly distant—public memory of heroism with a generative purpose for the present. Monuments, memorials, and the rituals of commemoration remain vital only if the living can shift their meaning and emotional power into possibilities for an impending future. From Selma to Selma to Selma, the Edmund Pettus Bridge is built and rebuilt by those who march across it.

About the Author

Allen Tullos is senior editor of Southern Spaces and associate professor of American Studies at Emory University. He is the author of Alabama Getaway: The Political Imaginary and the Heart of Dixie (University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Acknowledgments

For their helpful readings and comments, thanks to Cynthia Blakeley, Grace Hale, Michael Moon, Tom Rankin, and Steve Suitts. Thanks to Franky Abbott for her assistance with layout.

Recommended Resources

Useful in framing this discussion of the Pettus Bridge are Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995) and Georg Simmel, "Bridge and Door," in Simmel on Culture (London: SAGE Publications, 1997), 170–173.

Similar Publications

| 1. | Charles J. Dean, "In Black Belt, McCain Wins Hearts, Not Votes," Birmingham News, April 22, 2008. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Phillip Rawls, "McCain Takes GOP Campaign into Rural Alabama Democratic Turf," Associated Press, April 21, 2008; Charles J. Dean, "McCain Visits Gees Bend Quilters," Birmingham News, April 21, 2008. |

| 3. | Elisabeth Bumiller, "On McCain Tour, a Promise to Find 'Forgotten' America," New York Times, April 22, 2008. |

| 4. | Alvin Benn, "Historic Edmund Pettus Bridge Brings Fame, Fortune, to Selma," Montgomery Advertiser, January 5, 1992. |

| 5. | Jannell McGrew, "Discrimination Still Alive, Jackson Says," Montgomery Advertiser, March 10, 2003. |

| 6. | Alvin Benn, "Return to Selma," Montgomery Advertiser, March 10, 2008. |

| 7. | Michelle Malkin, "Queen of Cringe," New York Post, April 25, 2007; "The Big Story with John Gibson," Fox News Network, March 5, 2007. |

| 8. | Dahleen Glanton and Mike Dorning, "Clinton, Obama Commemorate Selma Anniversary," Chicago Tribune, March 4, 2007. |

| 9. | For Toni Morrison's comment see Wikipedia, s.v. "Toni Morrison," accessed May 6, 2008, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toni_Morrison. |

| 10. | Robert George on "News and Notes," National Public Radio, March 5, 2007. |

| 11. | Nedra Pickler, "In Selma, Obama Appeals to Black Voters," Associated Press, March 4, 2007; Tom Baldwin, "Quest for Black Vote brings Obama and Clinton to Heart of Old South," Times (London), March 5, 2007. |

| 12. | Glanton and Dorning; "Sen. Obama Delivers Remarks at a Selma Voting Rights March Commemoration," as released by the Obama Campaign, March 4, 2007. |

| 13. | "Text of Democrat Barack Obama's Prepared Remarks for a Rally on Tuesday in St. Paul, Minn., as Released by his Campaign," Associated Press, June 4, 2008. |

| 14. | Selma native Joanne Bland, later a co-founder and director of the National Voting Rights Museum, was eleven years old when she and her fourteen-year-old sister Linda participated in the Bloody Sunday events. See " |

| 15. | J. Mills Thornton III, Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002), 455–489. |