Overview

The development of the African American community in Atlanta is a fruitful subject for the study of race in America. Racial policy and practice in response to emancipation and the failures of reconstruction were evolving in Atlanta during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Blacks and Whites in a rapidly growing city made for a volatile mix of people and sharply conflicting agendas. The size and structure of the African American community and the nature of its business and institutional development reveal sharply the problems of race in the leading city of the New South.

Introduction: Defining the Subject

"The problem of the twentieth century," W. E. B. Du Bois wrote one hundred years ago, "is the problem of the color-line." He was referring to the worldwide hierarchy of race that places lighter people over darker people. As educator, writer, and political activist he dedicated his life to the struggle for racial equality. But long before his death in exile, sixty years later on the eve of the civil rights March on Washington, Du Bois knew well that the color line would divide the world through the twenty-first century and, more likely, for centuries to come.

As race has been a persistent problem, so too has the study of race. The difficulty of confronting the pain and guilt of racial conflict has made race a virtually taboo topic of discussion and an elusive subject of study. The constantly changing racial references are telling examples of the ongoing difficulties in addressing race in this country. "We shall," wrote teacher Leila Amos Pendleton, "as a rule speak of ourselves as "Negroes" and always begin the noun with a capital letter." Recognizing, however, that in 1912 the word was considered by some a term of contempt, she hoped that in time "our whole race will feel it an honor to be called 'Negroes'." From the use of "colored" and "Negro" to "African American," "Black," and "Bi-racial," the problem of naming and being named has reflected the struggles of the racial order. From "integration" of the 1950s through "maximum feasible participation" of the 1960s, to "diversity" of the present, the shifting terminology reveals the persistent problem of confronting race in public policy. But study promises clarity, forcing us to be explicit. Building effective frameworks for research may in time better structure private dialogue and public policy. This research guide is part of such an effort. It seeks to clarify terms, narrate critical developments, define issues, and identify relevant sources of information.The focus of this research guide is the African American community in Atlanta during the twentieth century. From the perspective of a specific community in a particular place at a critical period, studying race becomes more manageable and gains depth. Since race is pervasive in American society, a wide variety of topics and research strategies would be fruitful for study. The development of the African American community in Atlanta, however, is a particularly fruitful subject for the study of race. Racial policy and practice in response to emancipation and the failures of reconstruction were evolving in Atlanta during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Blacks and Whites in a rapidly growing city made for a volatile mix of people and sharply conflicting agendas. The size and structure of Atlanta's African American community and the nature of its business and institutional development reveal sharply the problems of race in the leading city of the New South. The research guide addresses the context within which the African American community evolved, highlights the community's development, and assesses the impact of race.

Context: Delineating the Environment of Race

Race and Place

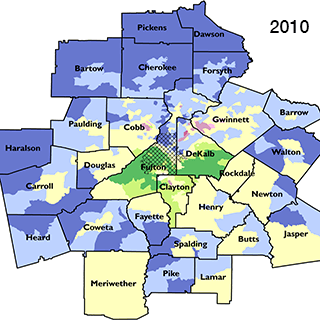

In a sense, the study of race has no geographical limits. The force of racism is global. The specific impact of race, however, will vary nationally and regionally. In the United States, where the presence of Blacks has been significant, power and resources are allocated primarily by race. In the American South where most Blacks have lived and had been central to economic production, racial restrictions have been extreme. But even within the South, there are sub-regional distinctions in the operation of race. References to Upper, Lower, Border, and Deep South imply differences in racial policy and practice that may be largely dependent on variations of geography and economy and on stages of development. And within these sub-regions, state, county and city jurisdictions may vary in the degree to which race dominates law and custom.

This research guide focuses on an urban landscape in the South, where a particular set of political, social, and economic relationships evolved following emancipation. What had been clearly ordered in slavery in an agricultural economy was subverted by freedom in the city. Atlanta is a case study of how these new relationships worked themselves out, how an urban area became the frontier of racial policy in the New South. Atlanta lies in the southwestern end of the urban industrial belt that stretches from Danville, Virginia, through Charlotte, North Carolina, and Greenville, South Carolina, and extends to Birmingham, Alabama. This swath of piedmont plateau at the base of the Appalachian chain supports the geographical and economic framework within which race can fruitfully be studied.

Bi-racial and Bi-ethnic Atlanta

Until recent decades, Atlanta's population, like that of the South, has been almost exclusively Black and White. Moreover, because Black labor and the racial climate tended to discourage large numbers of immigrants, Atlanta's foreign-born population was only 3% at the turn of the century. Race in America, particularly in the South, has tended to override ethnicity. Race and ethnicity, however, overlap. Both terms incorporate ancestry, geographical origins, and cultural traits. By this definition Whites and Blacks belong to ethnic groups as well as to racial groups. In the South they were primarily of British and African ethnicity. There is a critical distinction, however, between race and ethnicity that informs the study of race in America. One's ethnicity, unlike one's race, can change. The acculturation of America's Scotch-Irish, for example, has transcended their ethnicity. But race for the subordinate group is immutable. It is the biological given that generation after generation, in spite of any racial mixture or cultural assimilation, is never dissolved. Black ancestry, however distant or minimal, permanently identifies its descendants as Black. The immutability of Black racial identity is at the core of racism. White supremacy depends upon White racial purity. The absolute standard of White over Black would be subverted and unenforceable were Blacks allowed to breed out of their race.

The South, therefore, is hardly ethnically homogeneous as is often maintained. Only if the African American presence is ignored can one conclude that the South lacks ethnic diversity. Indeed, the South as a region is defined by its diversity, racial and ethnic. The biracial and bi-ethnic character that flows from British and African ancestry has driven the South, its politics, economics, and culture. The Atlanta story tells how American racism rose to new heights with the system of Jim Crow and how that system operated as both constraint and opportunity in the development of the city's African American community.

The Rise of Jim Crow

Although the Civil War overturned slavery, another system of racial domination was developed to replace it. Jim Crow, as it came to be called, reached its full flowering in Southern cities like Atlanta by the turn of the twentieth century. In the rural areas, the cotton economy ensured continuities in the control of Black life and labor. But in the city, where there were no such economic continuities, it was necessary to find new ways to secure White supremacy. And in a city like Atlanta where commerce and industry were in their infancy and where Black and White migrants were at times in competition for the same jobs and living space, Black subordination had to be institutionalized in law and custom. Jim Crow legislation reflected the failures of reconstruction as Whites were restored to political power and the controls of slavery were extended. The prohibition of marriage between Whites and Blacks was one of the first pieces of legislation that sought to protect the very heart of White supremacy. Making interracial marriage illegal denied to mixed race children all claims to White property and, more significantly, to White identity. The codes that restricted property ownership and the vagrancy laws that permitted forced labor were other early attempts to maintain the controls of slavery. The White-only primary and the institution of voter qualifications guaranteed Black disfranchisement. Blacks were subjected to racially segregated schools, streetcars, libraries, restaurants and parks. The urban environment created new opportunities for the application of Jim Crow. Atlanta relegated Blacks to separate elevators. The new zoo at Grant Park provided separate entrances, exits and pathways for Blacks and Whites. Atlanta became the first Georgia city to legislate segregation in residential areas. There was virtually no area of Black life that was not restricted by Jim Crow.

Community Development: Finding Unity in Division

Jim Crow and Black Institutional Autonomy

Held within the ever-tightening grip of Jim Crow, the African American community was forced to save itself. The Black church became the agency of temporal as well as spiritual salvation. The church was the community's first autonomous institution - one that could not be reclaimed by Jim Crow. As an all-Black organization, it was compatible with Jim Crow and the system's effort to control Black behavior. But removed from the ownership and power of Whites, the church was inherently subversive of White control.

In Atlanta, as Black migration from the country increased phenomenally, churches sprang up everywhere in Black neighborhoods, much as they had done in rural areas when Blacks withdrew from second-class membership in White congregations. By 1900 Black Atlanta was served by innumerable churches.

The impact of the Black church on the community's institutional development was profound. Because public education in Georgia was slow in coming and for most Blacks was unavailable, Black churches and White mission societies from the North took the lead in supporting African American education in Atlanta. In Atlanta private education at all levels for Blacks predated public education in the city for Whites. And within twenty-three years of emancipation, six private colleges were established in Atlanta, making the city a regional center for Black education. Though most of the students in these institutions were in elementary and secondary courses, within a decade of its founding in 1867, Atlanta University awarded its first bachelor's degrees. And within thirty-five years of emancipation, most Blacks were literate.

Together the church and the school sought the moral and intellectual redemption of a newly freed people. The church was in the vanguard of that mission, offering a range of social services before social agencies were founded and providing the facilities and financial support for schools. Schools in turn prepared ministers and teachers and reached out to promote the development of their surrounding communities.

A Community at Risk

Confined for the most part to the deteriorating neighborhoods east and west of downtown, relegated to the lowest paying jobs in common labor and domestic service, and effectively disfranchised, many Black Atlantans experienced after emancipation conditions that rivaled their hardships in slavery. The city was a harsh test of their survival in freedom. At the turn of the century, Black household income in Atlanta was only half that of White households. And as Jim Crow tightened its noose, Blacks lost the dominance they had had during slavery in skilled trades like barbering, shoemaking, and masonry. Low income and poor health comprised only one side of the conditions that placed Black Atlantans at risk. Jim Crow made for a volatile situation. Separation and exclusion in neighborhoods, schools, and public accommodations did not eliminate the potential for conflict between the races in the street and on the job. The politics of race heightened tensions still more. In an eighteen-month campaign for the governorship, Hoke Smith and Clark Howell debated the merits of Black disfranchisement with racist rhetoric. As news extra after news extra was published one Saturday night erroneously reporting attacks by Black men on White women, a crowd of carousing young White men grew to a mob of thousands of all ages and classes intent on wholesale lynching. The four-day rampage in which countless Blacks were slaughtered became known as the Atlanta Riot of 1906. It was worst incidence of racial violence in the state. Violence, not order, was the handmaiden of Jim Crow. The African American community and its institutions sought peace and protection as well as moral and spiritual uplift and social reform. A distinctive corps of institutional and business leaders managed these initiatives.

An Elite Leadership

Atlanta's leadership was largely professional and business elite: the ministers of the city's leading churches, college presidents and professors, physicians, and the prominent entrepreneurs and skilled tradesmen of the day. Relative to the masses of Blacks they were upper class, advantaged by income, education, and ancestry. They were for the most part light-skinned, a mixed race subcaste whose White ancestry had provided property, money, education, or a skill. The professional elite, who had trained at the normal schools, seminaries, and colleges in Atlanta and elsewhere were the "talented tenth," destined according to Du Bois to guide "the Mass away from the Worst." Because the needs of the community were so great and the leadership corps so small, Black leaders generally addressed more than their immediate area of responsibility. Ministers preached educational enlightenment and sponsored educational and social services. Teachers taught Bible for the moral uplift of their students, and businessmen were often the community's advocates in dealing with the White power structure.

One of the most prominent clergy in Atlanta was Henry Hugh Proctor, pastor of First Congregational Church, which like Atlanta University, was organized by the American Missionary Association. Under his ministry, the church conducted a number of community programs: afternoon Sunday schools at missions throughout the city; a home for working girls; a federal prison mission; and an employment bureau, cooking school, and library. W. E. B. Du Bois was among Atlanta's educational elite. As professor of economics and history at Atlanta University, he not only conducted pioneering empirical research on Black life, but also became the leading theorist and activist on racial equality. Challenging Booker T. Washington's accommodation to political and social equality for the sake of economic progress, Du Bois organized the Niagara Movement in 1905, the first Black civil rights organization in the twentieth century and the intellectual forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Through Du Bois, Atlanta became the focus of the national dialogue on the strategies for racial uplift. Participating in that dialogue was John Hope, the first Black president of Morehouse College and later of Atlanta University. As educational administrator and social activist, he fought Black disfranchisement and struggled to save Standard Life Insurance Company, one of the largest Black businesses in the nation; as the major advocate for University Homes, the nation's first black public-housing project, Atlanta became the laboratory for social engineering. Consistent with that effort, Lugenia Burns Hope, wife of John Hope, was instrumental in the Atlanta University's organization of the Neighborhood Union, the first social work agency of its kind in the South and a national model for other urban communities. If Atlanta was the laboratory of Jim Crow, it was also a laboratory for the Black community's institutional response to it. Clearly, Black progress was tied to an effective leadership. And in response to the divisions and exclusion of Jim Crow, Blacks struggled for unity. To survive they had to cooperate. To meet their needs they had to found their own institutions. To make money, they had to seek the Black market. Atlanta's business leadership was dominated by Alonzo Herndon, the city's premier barber, and founder/president of Atlanta Life Insurance Company, one of the largest Black financial institutions in America. Herndon's career spanned the major developments in Black enterprise in Atlanta. His business anchored the Auburn Avenue district, which in its heyday in the 1920s was considered the most significant Black business district in the country. Herndon's story captures a significant chapter of Atlanta's development as the commercial and financial center of the region.

Business Enterprise: A Window of Opportunity

|

| Photographer unknown, The Crystal Palace at 66 Peachtree Street, circa 1920. Courtesy of the Herndon Home. |

Atlanta as a fast-growing commercial center offered opportunities for Blacks as well as Whites to make good money. Having been founded less than twenty-five years before the Civil War, the relatively young city's business elite was newly arrived and untied to the planter society of the Old South. Atlanta's economy was supported by the railroad network that distributed cotton throughout the region and generated the growth of banks and brokerages, mills and factories. In addition, Atlanta was a lucrative market for Blacks in the building trades and personal services: barbering, tailoring, dressmaking, blacksmithing, masonry, carpentry, plastering, and painting. These were the traditional services that an elite corps of slaves had generally performed. After emancipation, they were the occupations that made for Black entrepreneurial success, but that were considered at the time too menial for Whites in the South. While such opportunities could not be considered areas of autonomy, they were, nevertheless, windows of business opportunity. In time as Jim Crow intensified, these windows would shut, but other windows of business opportunity would open. Ironically, Black business in Atlanta thrived on the crest of segregation. Whether in personal services that were a carry-over from slavery, or in life insurance in service to a Black market, Black business has profited from the racial order structured by Jim Crow. As Blacks lost their dominance in barbering to Whites by the early part of the twentieth century, Alonzo Herndon invested in life insurance for a Black community that had grown phenomenally by the turn of the twentieth century and could afford to support the mix of life insurance, banking and real estate that made Atlanta for Blacks and Whites a commercial and financial center.

Atlanta's Black business development was not unique. The story of Black barbering and life insurance is reflected in the career of John Merrick of Durham, North Carolina. Atlanta and Durham are both New South cities lying within the urban industrial belt of the Piedmont plateau. Both cities have Black institutions of higher learning that generated an elite leadership and the skilled managers for financial services. This suggests that research of the South's sub-regions is a promising framework for the study of African American community development.

Study Focus/Issues

1. The regional characteristics of geography, population, economics, and politics that shaped the development of the African American community in the urban industrial belt.

2. The factors that made Atlanta's racial environment distinctive.

3. Regional comparisons in racial and ethnic composition between the South and other regions in the nation and between sub-regions in the South.

4. Changes over time in the impact of race and ethnicity.

5. Comparisons in the evolution of Jim Crow between North and South, and between regions within the South.

6. Continuities in institutionalized racism following the Jim Crow period.

Recommended Resources

Baker, Ray Stannard. Following the Color Line; An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy . New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1908.

Dittmer, John. Black Georgia in the Progresive Era, 1900-1920. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

Doyle, Don H. New Men, New Cities, New South: Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston, Mobile, 1860-1910. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Du Bois, W. E. B. Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903.

Du Bois, W. E. B., ed. "Economic Co-operation among Negro Americans." Atlanta University Publications, no. 12. Atlanta: Atlanta University Press, 1907.

Frederickson, George. Racism: A Short History. Ewing, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Greenwood, Janette Thomas. Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White "Better Classes" in Charlotte, 1850-1910. University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

Henderson, Alexa. Atlanta Life Insurance Company: Guardian of Black Economic Dignity. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Kuhn, Clifford M., Harlon E. Joye and E. Bernard West. Living Atlanta: An Oral History of the City, 1914-1948 . Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990.

Merritt, Carole. The Herndons: An Atlanta Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Powers, Bernard E., Jr. Black Charlestonians: A Social History, 1822-1885. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865-1890. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Shapiro, Herbert. White Violence and Black Response: From Reconstruction to Montgomery. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Weare, Walter G. Black Business in the New South: A Social History of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1973.

Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Wormser, Richard. The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003.