Overview

Anne Kelly Knowles reviews Ian N. Gregory and Alistair Geddes, eds., Toward Spatial Humanities: Historical GIS & Spatial History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014).

Review

|

What are "spatial humanities"? Depending on whom you ask, this evolving term can refer to humanistic research that is explicitly geographical, or based on spatial databases, or uses digital methods to visualize the spatial aspects of human experience. The most complex formulation of spatial humanities comes from historian David Bodenhamer and his collaborators, historian John Corrigan and GIScientist Trevor Harris. They see the spatial humanities as a fusion of traditional humanistic attention to nuance, voice, experience, close reading, text, and image, with the systematic, analytical approaches of spatial science, computer modeling, virtual reality, and GIS (geographic information systems, computer software that places information according to its geographic location).1For a summary of this view of spatial humanities and its desiderata, "deep mapping," see David J. Bodenhamer, "The Potential of Spatial Humanities," in The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship, ed. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2010), 14–30. Toward Spatial Humanities is the fifth book in the Spatial Humanities series that Bodenhamer, Corrigan, and Harris edit for Indiana University Press. I serve on the editorial board and have a volume in the series, Geographies of the Holocaust (see Resources).

Toward Spatial Humanities shares Bodenhamer and company's aspirations. While the spatial branch of the digital humanities has received less attention than corpus linguistics, text mining, and topic modeling (methods developed by linguists and literary scholars), historical GIS (HGIS) has developed on the sidelines for just as long, beginning with mid-1980s projects such as David W. Miller's Great American History Machine. Editors Ian N. Gregory and Alistair Geddes argue that HGIS has reached a stage of maturity that will make it more interesting and influential to non-GIS users. Like a caterpillar emerging from its chrysalis, HGIS scholars who labored for years to develop methodologies and construct databases are now producing books and articles that offer significant new interpretations of the past.

The shift from empirically focused HGIS to the more general concept of spatial history is crucial, the editors argue, if scholarship based on GIS is to make a lasting contribution to the humanities. For many years, scholars working in HGIS tended to write more about what their databases had potential to achieve than about actual results. Some critics took the long gestation of HGIS as a sign that such projects would yield little, and that funding agencies were wasting their money. Now, Gregory and Geddes report, we are getting what we have craved: fresh descriptions of the past, revelations of previously unperceived patterns, and convincing causal explanations. Another sign of the maturity of historical GIS is its adoption by scholars in disciplines other than history and geography. A third indication is that humanists are using GIS more creatively by applying it to a wider range of sources and research problems. These ideas provide the loose organizational structure for the book. Part 1 offers three essays that exemplify spatial history. Part 2 adds three more essays that broaden GIS by applying it to new sources and disciplines.

|  | |

| Catholics in Northern Ireland as a percentage of the population 1km grid square, 2001. From Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland, 2013. Courtesy of Niall Cunningham. | Protestants in Northern Ireland as a percentage of the population by 1km grid square, 2001. From Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland, 2013. Courtesy of Niall Cunningham. |

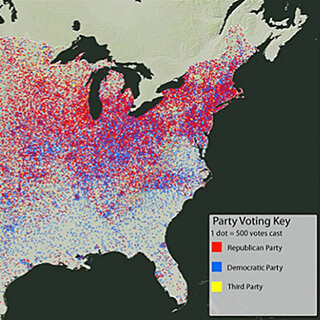

The individual chapters are very good examples of historical research based on GIS. Robert M. Schwartz's years of research on railways' influence on agriculture in late nineteenth-century Britain and France exemplifies exactly the trend toward interpretive maturity that the editors describe. Schwartz and Thomas Thevenin offer a fascinating analysis of railways' differing penetration of the French and British countryside, carefully noting what their GIS analysis reveals and leaves unexplained about farmers' choices to grow commercial crops or livestock as their neighborhoods became better connected to urban markets. This piece is classic social science history shaped by spatial visualization and tempered by the nuanced observations of contemporary writers. Andrew A. Beveridge, long a leader in GIS-based demographic history, uses mapping deftly to show patterns of residential segregation in American cities, 1880–2010, and then draws on statistical measures to probe those patterns further. While it is not surprising to learn that racial segregation intensified in Chicago, it is striking and disturbing to see the trend worsen steadily over so many decades. Niall Cunningham also takes a social-scientific approach to Irish religious history, mapping the changing concentration of Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland through the twentieth century, then diving down to the streets of Belfast and parishes in the North to plot concentrations of paramilitary and military deaths during the Troubles. Each of these chapters describes conditions and trends that help one understand how phenomena differed from place to place. Only Schwartz and Thevenin's, however, offers the beginning of a new interpretation—a revisionist history that Schwartz has addressed in a series of recent articles and will, one hopes, pull together in a book that explains connections between two huge sectors of the European economy.

Elijah Meeks and Ruth Mostern's excellent chapter on the politics of territory in Song Dynasty China (960–1276 CE) also reaches historiographic conclusions, though it has been positioned in Part 2 as an example of extending the use of GIS into new directions. Explaining database structure and methods can be the kiss of death for historical writing that aims to reach a non-technical audience. Yet Meeks and Mostern make the technical basis of their research interesting and pertinent to understanding their conclusions about spatial renovation (a wonderful term for the reorganization of political units) and political responses to catastrophic floods along the Yellow River. I would only recommend that Mostern and Meeks seek design assistance to make their maps easier to read.

|

| Mortality rate from lung disease among men aged 45–64, 1861 to 1870. From the Great Britain Historical Geographic Information System, 2012. Courtesy of Humphrey Southall. |

Humphrey Southall argues that scholars should try to apply HGIS beyond the Academy more often. Southall's chapter in Toward Spatial Humanities highlights his recent work as an academic entrepreneur who has been unusually resourceful in finding ways to make GIS databases socially useful. For example, he provided the demographic content of the Great Britain Historical GIS to medical researchers to give their studies greater historical depth, and he helped develop a neglected source of historical land use data to inform government agencies' efforts in environmental management.

"Mapping the City in Film" is an interesting effort by Julian Hallam and Les Roberts at locating sites represented in films and of film production, in and around Liverpool, England. The maps are fairly rudimentary, as efforts by relative newcomers to GIS often are, but they prove their value by prompting new spatial questions. In disciplines such as film and media studies, where scholars tend to be "ambivalent towards the use of empirical methods," (147), GIS poses epistemological challenges. Its embedded insistence on precise location (the one inescapably positivistic quality of GIS, as Gregory and Geddes note) raises questions for cultural studies of all kinds. Hallam and Roberts's dissatisfaction with the reductionist simplicity of using points to represent location in films led them to try more meaningful approaches, such as embedding "video and audio files of interviews, oral histories, and other ethnographic-based materials on the GIS platform" (154).

|

| Comparative smooth surface—places mentioned. This comparative map uses the 'smooth surface' technique to contrast all of the regional places mentioned by Gray and Coleridge as recorded in their respective texts. Image from Mapping the Lakes: A Literary GIS. Courtesy of Ian Gregory. |

Ian N. Gregory, a protean force in shaping the discourse and the adoption of GIS in history and the social sciences, is now extending his reach into the humanities. In addition to writing, co-writing, and editing definitive books and articles on historical GIS, he has taught several hundred scholars in his faculty workshops, all the while remaining a perceptive critic of the inherent limitations of GIS. He is now probing those limits in collaborations with humanists, such as in a notable study with David Cooper, mapping the rambles of Romantic writers in the Lake District as a first step toward understanding how they perceived and wrote about the region. Gregory is also developing methods for combining text mining with GIS, an idea that holds much promise for broadening HGIS beyond spatial history.

In sum, Toward Spatial Humanities is a good gateway into the evolving sub-discipline of historical GIS. Gregory and Geddes's introduction, conclusion, and endnotes give excellent summaries and references for further exploration. The case study chapters provide good examples of applying GIS to particular historical periods, places, and questions. We can never have too many cases for inspiration and guidance, for so much history remains unexamined from a geographical point of view.

About the Author

Anne Kelly Knowles is Professor of Geography at Middlebury College. Her recent books are Mastering Iron: The Struggle to Modernize an American Industry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013) and Geographies of the Holocaust (Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 2014). Both make extensive use of GIS.

Recommended Resources

Text

Bodenhamer, David J., John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, eds. The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

Cooper, David, and Ian N. Gregory. "Mapping the English Lake District: A Literary GIS." Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 no. 1 (January 2011): 89–108. See the accompanying website (http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/mappingthelakes/) for maps and further research.

Gregory, Ian N., and Paul S. Ell. Historical GIS: Technologies, Methodologies, and Scholarship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Gregory, Ian N., et al. Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013. See the accompanying website (http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/troubledgeogs/) for downloadable color maps and information about the project.

Knowles, Anne Kelly, ed. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Shaping Historical Scholarship. Redlands, Cal.: ESRI Press, 2008.

Mostern, Ruth. "Dividing the Realm in Order to Govern": The Spatial Organization of the Song State (960–1276 CE). Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2011.

Web

Beveridge, Andrew A., et al. Social Explorer. http://www.socialexplorer.com/.

Bol, Peter, et al. China Historical GIS. 2010. http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~chgis/.

Knowles, Anne Kelly, et al. "Interactive Map of the Battle of Gettysburg." Smithsonian.com. 2013. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/A-Cutting-Edge-Second-Look-at-the-Battle-of-Gettysburg-1-180947921/?no-ist.

Southall, Humphrey R., et al. A Vision of Britain through Time. 2009. http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/.

Similar Publications

| 1. | For a summary of this view of spatial humanities and its desiderata, "deep mapping," see David J. Bodenhamer, "The Potential of Spatial Humanities," in The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship, ed. David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2010), 14–30. Toward Spatial Humanities is the fifth book in the Spatial Humanities series that Bodenhamer, Corrigan, and Harris edit for Indiana University Press. I serve on the editorial board and have a volume in the series, Geographies of the Holocaust (see Resources). |

|---|